Two Florida natives build a life together in the beauty and peril of North Pole, Alaska.

Karin + Nolan // North Pole, Alaska

Stepping past the door to the jet bridge, and thankful to be out of the plane’s cylindrical belly, I turned my head towards a woman sitting nearby, waiting for her flight. She played a newscast on her phone, not bothering with earbuds or headphones. “The US has now reached 2.5 million COVID cases,” the reporter spoke with a practiced tone of astonished resignation. “Cases are spiking all over the country, and with no end in sight, what’s next for our country as…” The voice faded as I quickly shuffled away.

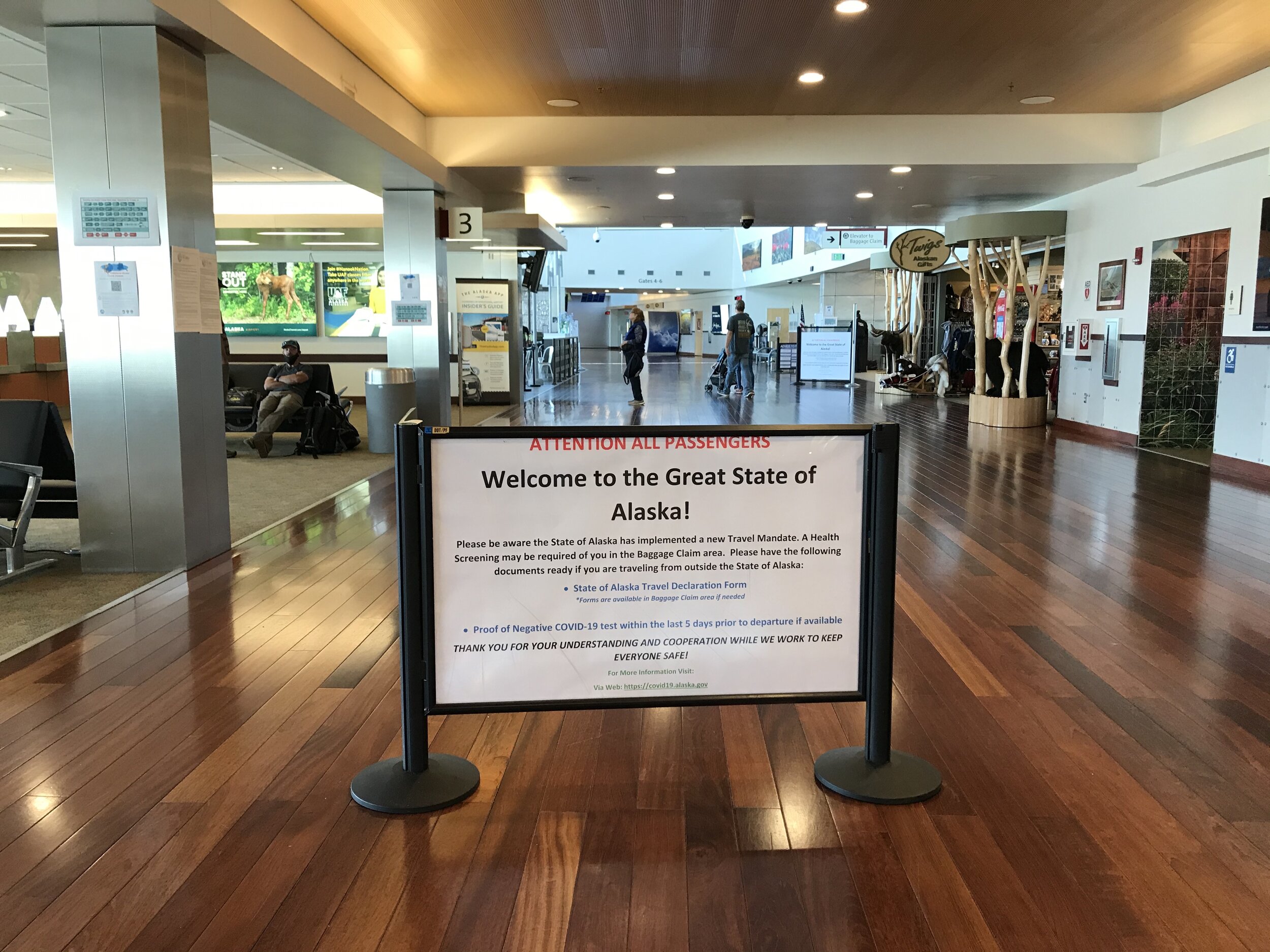

I took a moment to observe how this small airport in Alaska was responding to COVID-19. On the walls were advertisements about the state, clearly bought and placed long before the pandemic began. Some cited financial reward for moving to Alaska (“Great jobs, great pay! Relocation covered,”) while others highlighted tourism (“Your next perfect destination!”) In the center of the walkway stood a much larger, far more temporary-looking sign, still upbeat in welcoming you to Alaska, but clear in its reminder of the additional travel restrictions in place.

A summary of the new COVID-19 policies at the Fairbanks airport

Karin greeted me after I exited the screening area; the airport offered free on-site testing for those who didn’t land with a negative COVID-19 test, a move designed especially to protect the Indigenous population, who would have particular trouble accessing medical care should they become sick.

Like listening to the opening of Shostakovich’s 5th symphony, visiting Alaska is a sensorial journey that begins with a flood of inexplicable, primal emotion, and eventually settles into a more sublime yet tense peace. Alaska is nothing if not expansive; the spicy smell of countless evergreens dusts the breezy air, and the state is at once incredibly beautiful and incredibly existential, in the same way that looking up towards a cloudless, starry night sky makes you intensely aware of your smallness in the universe.

A drone photo of the Alaskan landscape

Those who live in this expansive wilderness are famously resourceful. Life adopts a different pace than somewhere more developed, defined less by the days and more by the seasons. Winter coaxes out heavy coats and holiday decorations, but also brings months of endless night, and seemingly few roots to civilization, as locals stock up on hundreds of pounds of firewood and freezer-friendly groceries before those frigid months. If they’re friendly, they’ll confirm that neighbors have done the same to prepare, too.

Denali National Park

Karin and Nolan weren’t born into this life, but they did choose it. Both grew up in Vero Beach, Florida, a city that hugs the state’s eastern coast between Miami and Orlando. They attended the same high school, two years apart. Both of their parents divorced fairly early in their lives, from which they drew a strong sense of independence. “We had to fend for ourselves at some different points,” Karin told me, speaking about herself, her twin sister, Sharon, and her younger sister of five years, Lori. “My mom and stepfather were pretty much gone 24/7. Sharon and I were cooking dinner for Lori, or washing clothes, or actually taking care of the house.” Their parents took care of the bills, and the siblings took care of each other.

Karin (center), her twin sister Sharon (right) and their younger sister Lori (left)

Florida didn’t suit Karin. “I wanted to get out of there and be an adult, have the freedom that comes with being older. As a teenager, I just wanted to grow up and not rely on friends or parents to do what I wanted.” (She mentioned a few times that she used to be a “wild child.”) Karin did Junior ROTC in high school, and decided to join the Air Force after graduation. “My boyfriend at the time was like, ‘Let's get married before you enlist!’” she said, rolling her eyes and swinging her head side-to-side. “Stupid. So my one and only marriage previous to this one was when I got married at 18.” I asked if she felt it was rushed. “Absolutely. We got married, and then 12 days later, I shipped out to San Antonio for boot camp. They were doing a physical on everybody when we got there; I found out I was pregnant. They put me on a bus, and sent me right back home.”

A photo of Karin from high school

“My entire future, at that moment, ground to a halt. I was not happy,”—she paused to emphasize that this was before she actually had her daughter, making sure I understood it was the situation she harbored disdain for, not her child—“and it was honestly pretty devastating.” Her marriage unraveled a year and a half later.

Karin’s daughter, Savannah, giving a speech at the reception

Nolan’s own parents divorced when he was around nine years old, after which he and his younger sister stayed with their father. “I love my mom to death,” he prefaced, “but back in the day, she didn’t make such great decisions.” Nolan didn’t dive into the details; I didn’t press.

Nolan on the wedding day

He continued. “My mom was a good example of someone who was never really meant to be a parent. We have a great relationship now… and it was nothing that she did maliciously…” Nolan searched for a way to describe how he felt. “It's just like… she just wasn't parent material.”

It was perhaps unfair of me to ask either Karin or Nolan to recall the details of their adolescent years, from which they’re decades removed, but Nolan graciously searched his memories. “The best way I can describe going through high school would be like getting in a car, taking your foot off the accelerator, and then dropping a brick on it. You're still steering, and you can swerve to avoid things, but you're not braking for anything.”

His thoughts started, then stopped, then started again. “And so I, you know… I'll be honest, I made it through high school and made it through my teenage years, and I mean…” Nolan let out a quick sigh. “I wasn’t… it was weird. I was one of those people that everybody knew who I was, but I wasn't really friends with a whole lot of people.”

Like Karin, he just wanted to leave. “I didn't like growing up in Vero Beach, which wanted to be its own little West Palm for so long.” Palm Beach, a strip of land about half a mile wide that runs parallel to the south Florida shoreline, hosted the area’s wealthier residents. Most of the people working for those residents—chefs, landscapers, maids—lived over in West Palm Beach. Nolan painted Vero Beach’s wealthier residents as trying to replicate the situation.

"When I was growing up, the people in Vero Beach, who were older and more conservative and had a lot of money, wanted to keep everything very low key. The whole mentality was, we can work here; wash their cars, mow their yards, serve their food, build their homes. But we were to live somewhere else.”

Much of what made Karin and Nolan’s wedding unique was not the wedding itself, but the days leading up to it. The two rented a campground for the week, originally to house up to 30 family and friends; COVID trimmed that down to just immediate family, and myself.

A drone photo of the campground and lake we stayed at

Our motley crew made home here, about 30 miles east of Fairbanks, and which comprised a dining hall, recreation room, wooden cabins housing suspiciously stained mattresses, and restrooms which offered a place to sit but not much else. The mood was that of both a summer camp and family reunion, at once physically liberating and emotionally straining. The youngest there, one of Karin’s nieces, was five, while the oldest, Karin’s father, was 76.

Karin and Nolan with Karin’s side of the family

For most weddings I document for Portrait of a Young Couple, I have the privilege of spending a bit of time with family and friends, usually in the immediate day or two before. That time is limited, and precious, though; I’m aware that a couple’s guests are there for them, not me, and I do my best to remain a wallflower so as to not overstep my welcome.

Chatting around the campfire a few days before the wedding

But here, in Alaska, I felt far less worry about being in the way. For one, there was simply much more space than at most weddings, and many more activities with which to preoccupy oneself. A fire pit invited anyone feeling chilly to warm themselves up, trails split off like tributaries from the main campground for those wanting to go on a walk or run, cabins offered a quiet moment of rest for tired kids, and the dining hall contained an ever-abundant supply of food and beer, no matter the time of day.

Karin’s brother-in-law making ribs for dinner

For another, summer in Alaska is a season of ceaseless light. The sun, like an energetic toddler who seems to never go to bed, swung brightly across the sky for 22 hours each day, dipping below the horizon only between 2 and 4 A.M., and returning to repeat the cycle the next day.

Taken around midnight one evening, when the moon was visible but the sun’s light was still present, too

With all of this—the intergenerational guest list, abundance of space, and steady daylight—came a natural sense of openness. Dozens of times did I or others break off into spontaneous pairs to sit out by the lake, grabbing a beer or fishing pole (or both) to accompany us, no pressure to talk, yet no awkwardness when we did.

Karin’s niece and her stepfather teaching her how to fish

At 24 years old, I was far closer in age to the kids present than to Nolan and Karin or their siblings and parents, yet it was easy to drift between conversations with anyone, young or old. Reading superhero comics to the children felt as natural as waxing poetic with the retirees about the wisdom they’d gained from decades of life.

Karin and Nolan told me to consider myself family for the week, and so I did, drawing closer to different members of the family in different ways. The kids loved my drone; their necks craned, hands held over faces to block out the sun, eyes darting across the impossibly blue sky, as the aircraft’s whirr grew quieter and quieter the higher it flew. Those with whom I was closer in age shared more reflective conversations, inquiries into each other’s experiences with school or hopes for the future. And with the “adults,” a sense of mentorship, patient listening, absorbing their stories and lessons to add to my own catalog of lives lived, relationships lost, happiness gained, or mistakes made by others in the world.

Dinner one evening at the campground

Karin and Nolan, playing host to all of this, looked visibly nervous most of the week, something I confirmed with them when we chatted after the wedding. “I was concerned mainly with my family having a good time,” Karin told me in a resigned voice. “I wanted their trip to Alaska to have been worth it.” She paused, and added, half-heartedly, “Because seeing me wasn't enough, right?” Her tone suggested she knew it wasn’t true, but her doubt was understandable. Flying to Alaska, with many kids in tow, was plainly expensive; doing so during a pandemic only made everyone more nervous. And those traveling to a family reunion carry physical, and emotional, baggage.

Everyone from the camp visiting downtown North Pole

Karin and Nolan met each other only a few times during high school. “We went on, like two dates, I think, but then went totally separate ways,” Karin tried recalling. They remember meeting up again a few years later to watch The Mask, a superhero comedy that starred Jim Carrey and Cameron Diaz. “It was a really memorable date,” she continued, “because I remember, coming away from it…” Karin cracked into laughter. “Thinking he was an asshole!”

“I probably was,” Nolan languished self-awaredly. I asked whether he knew why he’d come across that way. “I wouldn't say I was arrogant, but at that time I was a bit more naive, idealistic.” Karin followed. “If you didn’t conform to his ideals, then he just was not as open-minded or forgiving.”

Nolan told me a few times that he was an “acquired taste.” “When you first meet me, you either really love me or hate me. And then after that, it's like Diet Coke: hardly anybody likes it in the beginning, but you can get used to it after a while. I'm the same way.”

Nolan is at once a self-described hard-ass and a jokester who often tries to lighten the atmosphere around him. Perhaps what polarizes others’ opinions of him is how he decides to be each. Nolan works as a medical coder, an essential back-end job that complements the front-end care we receive through the health care system, translating a doctor’s often unstructured and scrawly notes into clean, computer-readable codes, which can then go on to be used for billing and record-keeping.

Karin and Nolan at Denali National Park

In our conversations about his profession, Nolan went on many detailed and long commentaries of his job (which he enjoys), and what it revealed about human psychology on a larger scale. I found it fascinating—my father works as a cardiologist, and he’s only occasionally told me about the logistics of his work—but Karin, more than once, dropped by to make sure Nolan wasn’t boring me to death.

Nolan used to work in law enforcement, and in some ways I found the two careers to be analogous. Both operate under the theory that positive results come from a combination of deterrence and enforcement. Just as the prospect of going to jail can be a deterrent to shoplifting, so hefty fines or license revocations can be a deterrent to incorrectly or even fraudulently filing medical codes.

As he shared stories of doctors or nurses ignoring his pleas to correct their processes, Nolan generalized. “You know, I think people are shitheads,” he said, confidently. “Ask anybody that knows me, I can't stand people. In general, they’re self absorbed, have the attention span of a gnat’s ass hair, and care about no one else but themselves.” He saw my face furrow with worry; I’m more optimistic towards humanity. “Now, individuals are different,” he qualified. “Individuals can be kind, and generous, and good. But people; we suck. We’re shit, as a species.” It was a colorful view into how he saw the world around him.

Nolan does, however, maintain some more adolescent qualities. He enjoys games—I often watched as he played Wolfenstein on his Xbox or explained board games laying around the house—and jokes around, even when it’s not totally welcome. The morning before their wedding, I joined him and Karin on a drive to the courthouse in downtown Fairbanks to pick up their marriage license prior to the actual ceremony. Karin was experiencing horrible migraines that morning, and Nolan tried cheering her up with a few stories of how their dog bothered her parents earlier that morning. Karin mostly ignored him as she closed her eyes and concentrated on making the pain go away.

For a time, Karin and Nolan successfully withdrew from Vero Beach, if not Florida. Nolan bounced around from job to job after high school, working at places like Pizza Hut and McDonalds. When I asked if he recalled having particular hopes for the future, he responded, “Honestly, I had a few thoughts here and there, but I didn't really think about future anything. I was just enjoying myself and having a good time; playing video games, hanging out with friends, and it was the early 90s, so lots of concerts.” He got as far as a few towns over and even spent a brief time in Tennessee before, as he described it, “the rubber band snapped me back to Vero Beach.”

Soon after having her first child at 19 years old and separating from her husband, Karin reconnected with a friend she’d known during high school. She decided to join him in moving to California. “We were going out there so that he could work with his brother, who had a painting company,” she said, “and we took two months to get there because we had no money. Louisiana, someplace in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Vegas; we’d detail cars for a week, and then drive on to the next stop.”

“My mother had just told me to get a life, and so the closest thing I could get to that was going the furthest I could away to California. Six months later, after finally getting out there…”

Karin stopped. She bit her lip and closed her eyes. “I was pregnant. And he was killed. Crossing the street. Yeah, he got ran over.”

Karin’s mom flew out to LA to pick her up, and drive her back to Florida. “So, now, I’m a single mom of two kids,” Karin said, “and it was just not about me anymore.”

Karin got a job answering phones at a doctor’s office, and when her second child was in elementary school, she went to nursing school. “I obviously wasn’t going to be a pilot in the Air Force, and nursing was a sustainable career. My mom had been a nurse, and I’d taken nursing assistant classes in high school,” she told me.

“My kids were the kids of a single mom, so I worked full time, and I did as much as I could with them. But I didn't do a whole lot at the school. I definitely wanted them to find their niche. I made sure that they went to summer camps to try different things.” Her son loved football, and her daughter took on a more artistic bent.

Karin and Nolan with her kids and some of their significant others

A few years later, her first husband, with whom she’d had her first child, came back into the picture. “I thought that I would be a bad mom if I didn't at least try to make it work with him, so that my kids would have an actual father. So we tried it again, and ended up moving from Florida to Kentucky.”

I started to understand what Karin and Nolan both meant when they said Florida was the black hole of their lives, sucking them back each time they tried to leave.

“Six months after we got to Kentucky, he decided he did not like it there, and left. I did not have the luxury of “deciding”, but apparently he did.” She returned to Florida, once again. Single, once again.

Karin owns a shop in downtown Fairbanks, called Until Midnight, that rents out formal dresses and accessories. During the week, she works as a nurse from 7:30am-4pm, and then goes straight to the store until 9pm. She’s there a full day on Saturdays. Our whole group visited it once, after the rest of Karin’s family had arrived in Alaska, so that Karin’s sisters and nieces could try on a few dresses. Karin had a look of anxiety and longing in her eyes.

Karin with her sisters trying out dresses in her shop

The pandemic hit right before Karin’s peak season for the year; May and June typically bring in customers from the local schools and businesses, with the former holding proms and the latter hosting spring and summer formal events. “I couldn't get any federal assistance, like that PPP thing or whatever, because I’m a single person running the business, and I don’t draw a salary from here,” she told me. She did receive $1,000 from another program, but, “How was I supposed to cover four months of lost revenue?” she said, to no one in particular.

Karin tidying up some of the store before others arrived

Her landlord had been kind about rent, but when we visited the store, Karin was in the process of figuring out whether she could make it work, or whether she’d need to sell. She’d been in the space for about two years, and as Karin took care of something in the back, Nolan gave me a small tour. “When we first got it, we tore all the walls out, and then we painted everything and sprinkled all the glitter stuff,” Nolan said. We walked over to the changing area and the mirror. “This is where people can stand and look at themselves, take their photos, change between dresses.” He pointed to a shelving area. “Clutches, accessories, shoes, it’s all here.”

The shoes + accessories section of Karin’s store

“We spent way too long getting this all set up,” Nolan continued. “Oh my god, it was a nightmare, like two months. Yeah, we were in here for almost two months working on it. We had… we had a timeline, but of course it all took longer.”

The conversation lulled into silence, the kind that emerges when you’re thinking less of what to say, but how to say it.

Sitting in the store waiting for more of Karin’s family to arrive

Karin spoke up when she came back, having overheard me and Nolan’s conversation. “I was kinda going for a New York vibe,” she said, looking around the shop. She let out a long sigh, and made a soft smile, looking nowhere in particular. “My baby.” She looked down, and spoke just loud enough for me to hear. “Probably have to sell it.”

Karin and Nolan locking up the store

Karin and Nolan reconnected almost 20 years after they first met in high school. Nolan moved to Alaska in 2010. His previous marriage had recently ended, and he was in a transition period after getting injured working for a fertilizer company. “I realized that I needed to take care of myself and figure out what I was going to do with the rest of my life, and that's when I found medical coding.” After qualifying for his certification, he sent out dozens of applications to hospitals across the country; the only one to get back to him was one in Fairbanks, Alaska. “And about six weeks later, I wound up here.” I joked that he’d finally fulfilled his dream of getting out of Florida; he was about as far as one could be.

Karin asked we take a funnier photo with her father pretending to be upset about Nolan (the gun was of course unloaded and pointed away)

But Nolan didn’t completely cut off his Floridian ties; a few of his family and friends still lived in the state. Once, when Nolan came to visit, a mutual friend of his and Karin’s told Karin that Nolan was in town. Karin couldn’t make it because of a surgery she was having, but the two reconnected a few weeks later over Facebook. They soon began regularly texting and Skyping one another. “I came back around Christmas time the next year to visit my mom and to see Karin,” Nolan said, “and that's when we went out several times and had a lot of fun. That's also when I met her kids for the first time.”

Neither could pinpoint if anything in particular had changed, 20 years after they first met, about their attraction towards one another. But it wasn’t hard to allow that, in 20 years, something had changed. “I don’t know if I was actively looking for someone,” Karin offered, “but I knew that once I found it, I wasn’t trying to take things slowly.”

Karin during the ceremony

What started as a suggestion by Nolan that Karin come visit Alaska for a few weeks (“If you’re gonna come all the way up here, it’s not cheap, and you’ll want to stay for at least two weeks to see everything”) turned into Karin committing to move up to Alaska with Nolan. One evening, back when they were first talking, Nolan made a comment over text that made Karin laugh, and she responded, “Oh my gosh, now I have to tell everyone that I’m in love with a crazy man.” “And then she completely freaked out,” Nolan said, chuckling, “because she said that she loved me over text, and didn't even mean to do it. It was just, like, dead silence.”

“I actually still have the screenshots of those texts,” Karin said, grinning.

Karin and Nolan after the pronouncement of marriage

While Karin was eager to move in with Nolan (and, she admitted, to leave Florida again), Nolan was more apprehensive. “I didn’t want her to move all the way up here, leave everything behind, six months later be at each other's throats, and now she's up here, all alone, in the middle of the Alaskan wilderness, because some crazy asshole convinced her to move here and now she was stuck,” Nolan told me, trying to show his resolve. “So I tried, I really did try, to convince her not to move. Not because I didn’t want to be involved with her, but because it takes a lot to live up here. Especially as time goes on, you have a bad winter, or, you know, you're just having a bad whatever.” Karin deadpanned, “Or, it might just be 2020.”

Karin, Nolan, and her second son Jonathan during their trip from Florida to Alaska

“Not only that, but I am not the easiest person to live with,” Nolan continued. Karin let out an exasperated breath. “I thought he was joking,” she said, pointing at him. “Nope, I was as honest as I could be, and she still came up here,” Nolan replied.

Nolan’s hesitant instincts proved correct. “I went through almost a solid year thinking I was stuck because I had no way out,” Karin said, “Not because I wanted to leave, but because of the anxiety of being so remote. But I've also come to learn in the last five years that while you are remote, you're not really too, especially as you make friends and meet people.” I saw this firsthand as I joined Karin while she ran errands, picking up eggs from a friend’s chicken coop, grabbing extra sheets left on another friend’s porch, or visiting a coworker and her dogs training for the Yukon Quest. “Out here, you can literally die, so people check on each other,” Nolan said.

Nolan and Karin after their first look

The two have been living together in Alaska since 2015. “I think both of us were kind of gun-shy,” Karin said. “You know, as far as the actual wedding ceremony. But we’ve legally been domestic partners since the first year.”

“As far as actually getting married, I think both of us really wanted to be sure that that's what we wanted. We had a discussion relatively early in the relationship, just because we were fielding these questions about marriage, and when we talked, we realized that neither one of us was really in a hurry to even remotely get to that point,” Nolan said.

Karin and Nolan a few years after she moved to Alaska

I wondered aloud how being older changed the dynamics of their relationship. “That's where the double-sidedness of having that life experience comes in: you have that experience to draw upon, but at the same time, that experience makes you hesitant about certain things. Plus, you have to deal with your own issues before you can have a relationship with somebody else,” Nolan said.

Nolan and Karin during a portrait session

Karin followed, “We agreed that we were both the type of people that were more likely to work on things than just get angry, but we also found out we were both very, very passionate people.” Nolan elaborated. “We had some major arguments. But we also had the experience and wisdom of being older, which, once we initially got past the, I want to murder everything around me phase, calmed us down.”

Nolan shared his thoughts on fights. “If you’re wrong, you’re wrong, but if you’re right, you're still kind of wrong. Because it doesn't matter if you're right or wrong, but how you deal with the other person. And sometimes, if you're right, you deal with them worse than if you're wrong. So, even when you're right, you're wrong.”

My eyes narrowed and brow raised as I parsed Nolan’s words; they sounded somehow profound, yet somehow not. “He thinks he's right all the time,” Karin grinned, looking at Nolan. “I don't think I'm right all the time,” he replied, “But I do know that I’m right a lot of the time!”

Karin and Nolan made sure to fill the week before the wedding with activities. Some, like visiting Denali National Park, were more for the adults than the kids; the drive was four hours, each way, and the kids complained endlessly on the way back that we hadn’t seen any bears or moose. (We did at least see some wild caribou, and many, many beautiful landscapes.)

Caribou at Denali National Park

A comically adult-like moment from the youngest member of our group

Other activities for the kids, like gold-panning, also proved to be ill-suited. (Turns out you need to be quite patient and disciplined to pan for gold.) But other activities worked for all of us. Downtown North Pole, Alaska, is appropriately Christmas-themed year-round: street lamps look like giant candy canes, Christmas colors fill the town no matter the season, and the Santa Claus house offers ornaments and Christmas plushies regardless of the month.

Frustration abounds amid the slow process of gold panning

The small bits of reward from gold panning

Inside North Pole’s Santa Claus house/store

Me in front of the sign for North Pole, Alaska

Among our most unique stops was a visit to Karin’s friend, who lived about 15 minutes down the same road as the campground and bred sleigh dogs as a hobby. Nuzzled amidst towering trees of the Alaskan forest was a large clearing that held dozens of kennels. We heard the dogs barking before we saw them; they probably smelled us even earlier. Their owner told us a bit about her journey racing in the Yukon Quest, the younger sibling to the famed Iditarod. Some of her dogs ran circles of anticipation, begging us to come over and play; others hid in their kennels, tired, or perhaps just shy.

One of the many friendly dogs we met

A shyer member of the pack, hiding in their kennel

Karin and Nolan’s actual wedding ceremony was short and to the point. Those in attendance were mostly the family with whom I’d already spent the full week, but around a dozen other friends from the local area drove in, too. (Pre-pandemic, more friends and family, particularly from Nolan’s side, were supposed to fly in and stay with us at the campground. Nolan had been disappointed, but understood his immediate family’s decision to stay in Florida and not risk catching COVID-19 on the flights or at the wedding.)

Karin’s sister helped out with her hair, her nieces with nails and makeup, and her nephew with an impromptu arch made from fallen tree branches around the campground.

Karin’s son, Jay Jay, who is currently going to college for his Bachelor’s degree in filmmaking, helped film a video of the wedding.

Credit: JxK Visuals

Karin and Nolan’s lives returned to normal immediately after the wedding, normal being difficult and a bit stressful. “I'm just trying to get things either up and running or in a place to sell it,” Karin told me about her shop a few weeks later. She had previously been on medical leave from her nursing job, and after some internal politicking, decided to quit.

“I felt like you were kind of absent,” Karin said, as she looked over at Nolan. “I was petrified the whole week, to be honest,” he replied, chagrin written on his face. This platform is not a space for gossiping about family drama, but suffice it to say that there’d been tension throughout the week.

When I asked what the future held for the two of them, they answered that the upcoming winter was all that was on their minds. “How are we going to make sure that we have enough gas or firewood so that we don’t freeze?” Nolan posed. “Because if we lived in Florida, or most other places, and didn't have enough electricity to run the heat in the winter, yeah, we'll be a little cooler, but we’re not going to freeze to death.” His tone turned serious. “Up here? Yeah, that happens.”

“Not only that, everybody is going stupid, and crazy, and stupid crazy.” (He referred to the heated political and social climate sparked, in part, by the pandemic.) They were at least somewhat shielded from the fray by virtue of their physical isolation.

Karin’s demeanor shifted, suddenly excited. “But, I also just found out I’m going to be a grandma!” Her son and his girlfriend, who live in Vero Beach, had just shared news that they were pregnant. “I guess the black hole of Florida might suck us back again,” she noted, more cheerfully this time. Nolan narrowed his eyes, and slowly turned his head. “Maybe we can convince them to come here, instead.”