Maria, the oldest daughter of Mexican migrant farm-workers, and Yeison, a DACA recipient, recognize the privileges they have within their community. How are they using those privileges to lift others?

Maria + Yeison // Immokalee, Florida

As I checked the radar on my phone's weather app one last time a few minutes before Maria and Yeison’s wedding ceremony began, I squinted at the clear, blue, sky, and could scarcely believe their good luck.

In the days before, I'd kept an agitated eye on the weather forecast, voicing frequent but hollow hopes that the ominously dense rainclouds on the radar would magically disappear on their wedding day. There was no backup location for the ceremony, and though I've photographed weddings in the rain before, I'd hardly consider it to be ideal.

Maria and Yeison’s ceremony location before their guests arrived

And so, when I woke up early that morning and saw that the rain had not just changed direction but disappeared entirely, I was ecstatic, and surprised that neither Yeison nor Maria shared my enthusiasm. "Yeah, Florida's like that a lot," they shrugged. "The weather just changes suddenly." Where most couples would've been like me, fretting over the weather and praying to their deity of choice for a sunny wedding day, Maria and Yeison were simply grateful the day was happening at all.

A traditional Mexican wedding centers around three things: faith, family, and community. Mexico's overwhelmingly Catholic culture leads most couples to perform their wedding ceremonies in churches; flocks of aunts, uncles, and cousins balloon official guest lists to hundreds of people; and word-of-mouth invitations spread quickly through tightly-knit communities as friends and neighbors show up, en-masse, to afterparties.

Maria and Yeison, who are both Mexican-American, originally planned to host such a wedding, but the pandemic forced them to part from tradition.

Maria and Yeison during their ceremony

In size, a big wedding was out of the question, and after agonizing for weeks over whom to invite, they eventually narrowed the list to 25 people, to the disappointment (and occasional anger) of those who didn't receive an invitation.

But in spirit, Maria and Yeison strove to still honor their culture and their families. Their officiant, Mike, who also serves as their pastor, conducted the ceremony in a mix of both Spanish and English. They performed rites for las arras and el lazo, the former a set of gold coins gifted by Yeison to Maria as a symbol of his promise to provide for her, and the latter a unity ceremony whereupon Maria’s older brother, Juan, and his wife, Becky, draped a loop of ribbon and rosary beads around their shoulders, symbolizing unity under God. During dinner, a mariachi singer belted passionate sonnets of Mexican ranchera and romantic ballads.

Maria and Yeison enjoyed themselves throughout the day, and though the wedding was not without hiccups—their ceremony started half an hour late, and they discovered afterwards that the Facebook Live stream they set up had been upside down the entire time—in the end, they told me, none of that really mattered.

"The day was just so nice," Maria shared as we caught up a few weeks after the wedding. "We had so much support before, during, and afterwards; so many people going out of their way to help us, or send us a gift, or just send some kind words our way."

"I thought it was perfect, to be honest," Yeison added. "None of my family could be there, but a lot of them were watching from Mexico. It's just so rare nowadays to see a wedding happen, and I think it was nice for them to experience that." He and Maria smiled at one another, and gently clasped each other's hands.

Late one afternoon a few days before the wedding, as the swelteringly hot Florida sun finally began to set, a knock sounded from the front door of Maria’s childhood home. The home is technically mobile, but it’s sturdy, and located near the edge of town at the end of a narrow, bumpy street that is long overdue for re-paving. Through the front door was the kitchen, where large piles of onions and tomatoes scattered on tables and in large bowls; a papaya tree grew next to a window, its fruit providing the family with sweet refreshment year-round.

The papaya tree outside Maria’s mother’s home

Maria no longer lived in the home, but visited frequently to see her mother and younger siblings. We were all gathered in the kitchen when we heard the knock. Sylvia, Maria’s youngest sister, answered the door. “Yeison!” she exclaimed, laughing and throwing up her hands. “You’ve been coming here your whole life. Why do you still knock?? Just come in!” Yeison smiled, but didn’t say anything. He'd just gotten off work, and looked fatigued.

Maria’s mother had been wrapping a sizable stack of tamales, well-known in the community for being deliciously authentic. She looked in our direction, and asked what kind and how many we wanted. “Dos de pollo, por favor,” Yeison said, asking for two chicken tamales. I timidly rose my hand as well to ask for two pork tamales, gathering the scattered remains of the Spanish I’d learned back in high school.

The kitchen inside the home; behind was a table with piles of more tomatoes and onions

Maria’s mother lined a well-oiled pan with half a dozen tamales, turning them every few minutes until their outsides charred and the kitchen filled with the delectably aromatic smell of cumin, onions, fried masa, and peppers. “Careful, they’re hot,” she said in Spanish, as she placed two each in front of Yeison and me. She suddenly looked as if she’d forgotten something, and quickly turned to open the refrigerator, pulling out a Tupperware container of guajillo salsa, made from tomatoes and chile de arbol. She made a motion to me indicating I should pour some on top of the tamale.

As Yeison and I gingerly unwrapped the tamales from their scalding corn-husks, he looked towards Maria’s mother, who’d returned to the stove to fry more for her other children. “Her mom is almost like a second mom to me,” Yeison said. “I would always come over, and she would always feed me.” I asked if he had a favorite food that she made. He paused to think. “I think these,” he finally said. “There’s something about the taste that only, like, a real Mexican woman can get right.” Maria looked up, interjecting, “Hey, why does it have to be a woman?” Yeison thought about it, and shrugged; Maria was right, he supposed.

Immokalee, where Maria and Yeison both grew up, is a town of 26,000 people located in southwestern Florida, about 25 miles inland from the more well-known (and much wealthier) coastal cities of Naples and Fort Myers. That agriculture forms the nucleus of the city’s economy is quickly obvious from a drive through its streets: signs marking the farms and local packing houses—where workers pack fruits and vegetables into boxes to be shipped across the world—dot the community, as do trucks filled with the day's harvest or buses shuttling workers to the fields each morning and back to town each evening.

Google Maps Street View of one of the many packing houses lined next to Main Street in Immokalee

Most of the town’s population comprises immigrants and their families from Mexico, Haiti, and Guatemala. Many are undocumented. “It’s a very marginalized community,” Maria told me, “truly a community of first-generation, immigrant, migrant farm-worker families. I feel there are probably, like, three white families in the whole town.” (The exact demographics from the 2010 census placed the Hispanic population at 72.1%, and the non-Hispanic white population at just 5%.)

I’d coincidentally first heard about Immokalee shortly before Maria and Yeison reached out to me early in the summer of 2020, when national news shed light on the local government’s non-existent pandemic response. Most of the families who employed the town’s agricultural workers were doing nothing to protect their workers; many actively called the pandemic a hoax.

“It’s not easy,” Maria told me about the physically exhausting picking and packing jobs most common in the community, “but people are willing to do it, because at least then they’ll have some sort of income. Many make less than minimum wage, and they send all the money they can back to their families.”

Maria’s family used to be among these workers. As a child, she moved regularly between Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina, following her parents as they, in turn, followed shifting harvests across state lines. “My siblings and I have all been born in different cities, often different states,” Maria shared. “Because of this, I always knew that people were temporary in my life.”

Maria (blue shirt) with her mother and siblings

Maria’s one source of stability was her family, and she looks back fondly at her and her siblings’ ability to have fun in the plainest of environments. “We played on our own as our parents worked. When we were still small enough, we’d take the large buckets that tomato pickers used to carry tomatoes and fill them up with water and soap so that we’d have our own little personal pools. We’d sometimes throw rotten tomatoes at each other, or race each other in the fields, or play out in the dirt and make mud pies.”

On Sundays mornings, the family would go to church; in the afternoons, they'd enjoy picnics as a family. “My siblings and I were very endeared in church," Maria said, "so we always knew that people were looking out for us, no matter what.” She described the simple gestures others made for her and her siblings, making pies out of frozen peanut butter or whipped cream as treats for the children, and attributed her current love of connecting with people to that support that she felt as a child. “Thinking about it now that I’m older,” she said, “a lot of my childhood was just very simple.”

When she was in 6th grade, Maria’s parents separated, and her mother took the children and established firmer roots in Immokalee. Maria met Yeison, who was friends with her brother Juan and a year younger than Maria, towards the end of high school. “Yeison would be at our house a lot,” Maria told me, “and he was at a lot of our celebrations, like our birthdays or major holidays.” I asked Yeison what drew him to the home. “I think I really enjoyed that environment,” he replied, “Because, I guess, I just didn't know what it was like to have a sibling or a family, really.”

Yeison and Maria in high school

The two claim not to have seen each other as anything more than family friends. “For a long time, it felt weird to think of Yeison in a romantic way,” Maria said. She paused, thinking. “He was so nice, and I think I subconsciously knew he would be a good boyfriend, or something. It never got to that point because he was so close with our family and I felt that would complicate things. I don’t… I don't even know what it was… his green eyes…?” She laughed, realizing the observation was somewhat trivial.

A photo Maria took of Yeison’s green eyes

Before Yeison was a man of few words, he was a boy of few words, and perhaps the reason Maria and others knew him for his eyes was because of how little they knew him for the thoughtful mind behind them.

Yeison in elementary school

Although Yeison found a comfortable physical home in Maria’s family home, he never quite found an emotional home there, preferring to process his thoughts in the solitary space of a baseball outfield. “Baseball really… helped to take my mind off of things,” he shared with me. “I guess it was a good way to cope.”

Yeison playing baseball back in high school

After he graduated from high school, Yeison stopped visiting Maria's family. “I began working out a lot since I felt like I didn’t have baseball in my life. I was trying to find a sense of drive,” he said. “I think I enjoyed it because it helped me to distract myself from the loneliness, and I always knew that it was better than other things, which would take me to a place I didn’t want to be.”

Before I arrive at a couple’s home, I’ll ask to get on at least one long video call with them, which usually lasts around three to four hours. Many couples find these calls, taken while sitting comfortably on their couches and still months away from the stress of the wedding, to be the most natural way to share deeply about their lives. We'll talk about the things that are most important to them; the experiences, values, and people who've shaped them into who they are now.

But for some couples, a video call, no matter how long it is or where they take it, still feels stilted, awkward, and unnatural. I felt this with Yeison; much of what I learned about his story came not in our calls before my visit but from late night talks during it. The Friday night before the wedding, he guided us to a nearby lake that he used to frequent.

Illuminated by the dim, yellow lights of the parking lot, we walked towards the lake and onto a small pier built for sightseers and fishermen. Yeison looked out across the glossy, black surface of the water. “This lake was where I would always go by myself to think and reflect on what was going on in my life,” he said softly.

I cautiously nudged our conversation towards his earlier years. He’d shared fragments of his story coming to the United States on our calls before, but I’d noticed his unease speaking about it then and hadn’t asked about details. Amid the darkened sky, lake, trees, and air around us, he seemed more comfortable sharing.

Yeison was born in Mexico, and grew up surrounded by his grandmother, aunts, uncles, and maternal cousins. His mother was from Veracruz and his father from Guerrero, and the two met when their families moved to a city called Matamoros. What Yeison remembers from being in Mexico, he remembers fondly. “I enjoyed it," he said. "I was just out there riding horses and stuff, and I remember playing marbles, or hiding behind bushes and shooting a slingshot with my friends.” He didn’t share much of his parents’ own stories, but did say of his father, “He has a lot of trauma too, and I'm grateful he came here so I could grow up here in the US.”

Yeison (left) with his younger brother (right)

When Yeison considers his experience crossing the US-Mexico border, he says he “had it pretty good.” Yeison was six years old at the time. “We were living in Matamoros, and on the US side was Brownsville, Texas. My father had a job, and my mom had a visa, so we just took a Greyhound to Florida.” Like Maria’s family, Yeison’s was one of migrant farm workers.

Home life was complicated. “I remember witnessing arguments between my parents when my dad would drink,” he said, “but my mother died two years after we got to the US during childbirth, and that really changed my dad. That’s when he stopped drinking.” He recalled the memory of his mother. “She was always a beacon of positivity in the family; tall, athletic, and had a beautiful heart. I still remember her dressing me for school here in the US soon after we moved.”

Even after she passed away, Yeison has felt her presence during important moments in his life, as if she were making sure he knew he wasn’t alone. “I know she’s been with me through thick and thin, and it’s hard to believe how lucky I am still to this day,” he said.

After his mother passed away, Yeison’s two younger siblings went back to Mexico to grow up with their maternal grandparents. (Yeison lost touch with them, and it wasn’t until nearly two decades later that he found his younger sister on Facebook and reconnected with his family in Mexico.) He stayed with his father in the United States, and learned life lessons through experience rather than talk. “I don't think my father really knew how to guide me, because all he ever did was work," Yeison said.

Towards the end of high school, Yeison became more aware of what it meant to be undocumented. “I think it was always in the back of my head that I can't be doing anything dumb,” he told me. “Subconsciously, I think it made me really passive and quiet because I couldn’t do many of the things my friend did, such as get a driver’s license. My friends were experiencing the normal parts of coming of age and I felt like I couldn’t do the same.”

Few people were aware of his status; even Maria and her family didn’t learn until much later. “I always just thought of him as playing baseball and being my brother's friend,” Maria said, while one of her sisters told me, “Yeison speaks Spanish and English like most of us, and we never really thought of him as someone who would be undocumented.” In Immokalee, where matters of immigration status affected most families in some way, people rarely asked outright whether someone else had papers or not.

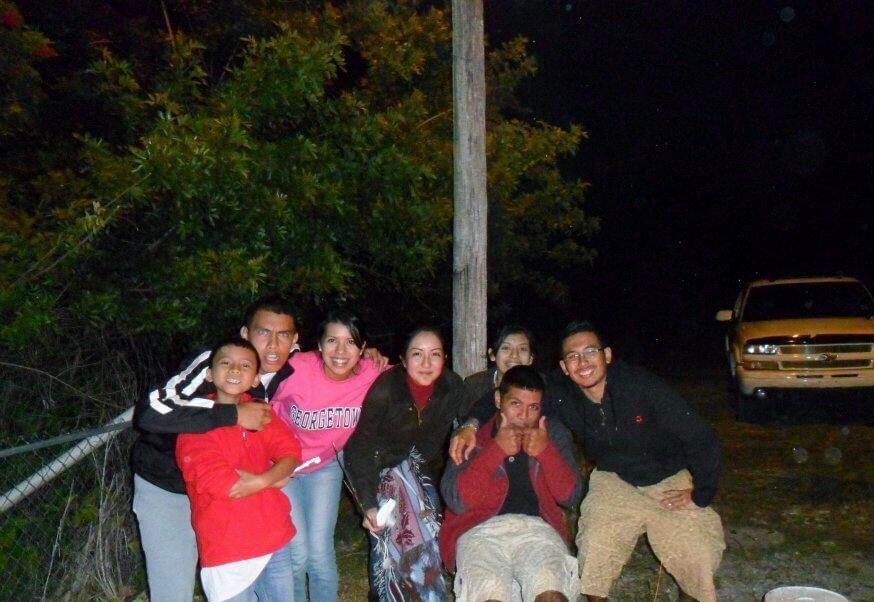

An old photo of Yeison and Maria (second and third from left) with some of their friends and siblings

Today, Yeison doesn’t keep in touch with many people from his youth, in part because, like Maria, his childhood tracked the temporary life of migrant farm work. Some people, like acquaintances from high school, he simply fell out of touch with. Others, like those he spent time with before becoming a Christian and finding motivation in life, he cut out. Those who remained in his life were either in Florida or from his church. “One of my good friends is on the East Coast,”—he meant of Florida—“north of Miami, another close friend has moved with his job a few times before resettling in Fort Myers. And then..." He stopped for a few seconds to be sure. "Then there’s my barber, who’s also my roommate, and the friendships and mentors I’ve gained at the men’s group at church.” He noted, disappointedly, that many of those friends hadn’t been able to come to the wedding because of the pandemic.

I’m often not sure how to respond when others ask me, “What’s your job?” If I need a short answer, I’ll usually just say “photojournalist and writer,” and hope that’s satisfactory. But if I can share the longer answer, I’ll admit how, sometimes, I'm not sure either.

My relationship with couples blends both professional courtesy and personal friendship. The interview process and ethical guideposts I employ are borrowed from formal journalism, but the deep connection I form with couples is one I treasure as much as I would with other close friends of mine.

That our relationship forms this blend is exciting, because it allows me to borrow elements from both and merge them into something unique. I can become more meaningful friends with someone because I have the reason to ask deeper questions as a journalist, while also becoming a better journalist by leaning on the trust built in our friendship to dive emotionally deeper into someone's life.

I reflected upon this as I spent time in Immokalee, and analyzed the emotions I had of how different life was there compared to my own. The responsibility to journalistically document the community as not just a footnote in Maria and Yeison's story but an entire chapter felt obvious, and the chance to learn about that community in meaningful ways came by means of my friendships with Maria, Yeison, and their families.

Bianca, one of Maria’s sisters, took me around the town one afternoon when Maria and Yeison were both at work. We first visited the local farmers market, where relatively few people gathered because of the off-season and off-hours; many of the stalls stood empty.

The market in Immokalee

It was a blindingly bright day, and demoralizingly hot. Bianca bought both of us a cup of agua de jamaica, or Hibiscus iced tea, and told me about how the market was a gathering place for everyday people. “Here, you see who makes up the town; people who are considered invisible in this society. You see their hard work," she said.

A stand where we bought juice and fruits

I watched as a man standing in a trailer handed watermelons to another man standing on the ground, who then placed them in neat piles to be sold wholesale later in the day. Another pair worked nearby to split a large pile of unhusked corn into smaller boxes for shipping. Still more pulled in with trucks full of fruits and vegetables destined to pass through countless more laboring hands before reaching a dinner plate somewhere around the world.

Men working in the market

Another afternoon, I visited a local laundromat to wash my clothes. Inside, I found it difficult to navigate through the two dozen others also doing laundry, some folding clothes on a table in the corner, others pushing quarters into the machines, most standing idly by, scrolling on their phones, waiting for their loads to finish washing or drying.

When I parked, I hadn't expected to find so many people inside; my car was one of only three in the parking lot. When I told Maria and Yeison about my observation, they pointed out that the town was pretty small, so a lot of people just walked everywhere. They also reminded me that undocumented individuals couldn't get driver's licenses.

"So many in this community have so many barriers that we don't have," Maria said, referring to herself and her siblings, who were all born in the US. She spoke about the wider undocumented population in Immokalee, and its reluctance to fight for rights and better treatment. “Lots of undocumented people don’t feel comfortable protesting, because they obviously don't want to get arrested. Organizations here in town such as the Coalition of Immokalee Workers have been advocating for years for the human rights of farmworkers and those who are undocumented.”

“People sometimes argue, ‘No, you should have just entered the US the right way.’ But not everybody really has the opportunity to do that.” Maria's words echoed others I'd heard recently: that in order to make good choices, you have to first have good choices.

Even for someone who grew up in Immokalee, Maria is highly knowledgeable about her community. On the night of my arrival, after she made sure I was comfortable and well-fed following my drive to Florida, Maria took out a map of the town. She'd hand-written labels denoting the locations of neighborhoods, farmworker housing developments, markets, and community centers, and began giving me an encyclopedic description of the town. "It's a very unique experience coming to Immokalee and seeing how everyone's cultures are mashed together,” she said, “as well as seeing a lot of the injustices in the community. There's a lot of history behind it."

An annotated map Maria made of Immokalee

Later in the week, she gave me a tour through Immokalee to pair her prior words with real places, pointing out neighborhoods of trailers, communities of cookie-cutter government-built housing, and a lot of temporary homes that at the moment stood empty but which, when the tomato harvest began, would fill with families like hers from childhood.

In Immokalee

Maria described the issues surrounding housing as we drove. “Most are multiple-family homes, because there isn't enough housing," she said, "and it's still too expensive for people to actually be able to afford it, because we’re part of Collier County, which includes Naples.” Even mobile homes usually cost people over $1000 a month in rent, when farm work might only pay $200 per week. She attributed the high rents to the county’s high impact fees, the cost developers had to pay to build on a piece of land, disincentivizing developers from building affordable housing which would bring in fewer profits. Average wages, pushed low by agricultural employers knowingly exploiting the cheap labor of undocumented immigrants, didn’t help.

In Immokalee

“Some people don't see Immokalee in a positive light,” Maria told me. “Naples and Fort Myers are pretty close, but Naples especially is a different world, and where your wealthiest people live.” The visual transition driving the 40 minutes from Immokalee to Naples was astounding: trailers turned into mansions, unpaved roads into immaculate eight-lane throughways, and the sight of children running and playing between unfenced homes replaced by tall brick walls that formed the perimeter of massive gated communities.

Immokalee was most recently in national news because of how it so stunningly represented the inequities present in the US’s pandemic response. The problem was posed most clearly in an op-ed that Greg Asbed, the founder of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, wrote for the New York Times:

"Picture yourself waking up in a decrepit, single-wide trailer packed with a dozen strangers, four of you to every room, all using the same cramped bathroom and kitchen before heading to work. You ride to and from the fields in the back of a hot, repurposed school bus, shoulder-to-shoulder with 40 more strangers, and when the workday is done, you wait for your turn to shower and cook before you can lay your head down to sleep....

Their dilemma is painfully simple: The two most promising measures for protecting ourselves from the virus and preventing its spread — social distancing and self-isolation — are effectively impossible in farmworker communities."

The nearest hospital to Immokalee is located an hour west in Naples, and getting there in even that much time requires a car; the only bus that remotely represents a path to the hospital loops ten miles south of it and takes twice as long, at nearly two hours, each way.

“When COVID happened,” Maria told me, “it was really bad, because a lot of people working in the farms had their hours cut in half or entirely. I know people who were saying, 'I know they’re telling us to stay home to stop the spread, but if I don't go to work, I don't eat.'"

Maria spent a few months working for Doctors without Borders (which, it should be noted, rarely operates in the US) to conduct testing and to educate the community about COVID-19. Her sister, Bianca, who’s studying to be a Physician Assistant, also worked for the organization, and both of their Spanish fluencies were hugely helpful. “Imagine how you’d feel if you were here and didn’t know English, trying to explain to a doctor what’s wrong with your body," Bianca said to me.

Maria while working for Doctors Without Borders. Credit.

The Coast Guard had initially been deployed for a few days in early April to help with COVID-19, testing, but the militarized presence scared away many locals already wary of government officials and outside organizations. When Doctors Without Borders came, they partnered with local community organizations to spread the word of their mobile clinics through trusted sources, and picked testing locations to which farmworkers could easily walk. “It was a heartbreaking and emotionally charged role,” Maria said to me, “but we were grateful to serve the community in such a desperate time.”

After Maria finished giving me her tour of Immokalee, she guided me to her mother's home so I could meet her. With Maria translating for us between Spanish and English, I learned that her mother hasn’t gone back to Mexico since immigrating to the US two decades ago; that Immokalee was a lot more developed now than in the past; that there used to only be two pay phones in town, and you’d have to wait for hours to call home; that now, with FaceTime, she could call her parents and see them every day; that she enjoys watching Korean soaps because of how dramatic they are; that she sells her tamales in the market most mornings before the field workers head out to work; that on Fridays, after many workers were paid, they would buy them by the dozen to enjoy at home with their families; that she occasionally wonders if she should’ve stayed in Mexico because the reality of living and working in the US wasn’t anything like she thought it would be.

“I never thought I’d be in the US to make tamales,” she half-sighed, half-laughed later in the afternoon as she returned to the tender repetition of her work.

Maria’s mother wrapping tamales

Maria runs an Instagram page called Roots of Immokalee, where she interviews people in town, writes some of their story, and shares it on social media. She cares deeply about injustices she sees in her community, and what energy she has left after the stresses of work and family is spent on helping others.

From this Instagram post: In an age where kombucha has taken over as a health craze, artisanal business owners are priding themselves in keeping alive their cultural tradition of tepache, a probiotic-rich fermented pineapple drink. Traditionally, this drink was made by the Nahua people in central Mexico and was made with corn as the base. Nowadays, you’ll find it made with either pineapple rinds or corn. It was used in many households to calm stomach nerves, aid in digestion, and provide a refreshing drink on a hot day. As soda manufacturing companies sought to import their carbonated beverages, traditional drinks such as the tepache were essentially seen as less then.

A Oaxacan couple keeps the traditional alive at the local farmers market. Rafa abs Diana originally worked in agriculture, but started working in la marketa in 2007. They specialize in natural fruit juices, traditional tostadas, hot chocolate bars, and molés imported from Oaxaca. Their natural fruit juices are made fresh daily. The tepache is made daily as well, but it requires sitting untouched for days to ferment. This gives it a fizzy tart taste and reddish coloring.

Not all tepache is made the same, even within the same country. Tepache recipes are passed down from generation to generation. This particular recipe has been in Diana’s family for generations and it is expected to be kept as is. Although she has stopped coming to sell at the marketa due to Covid-19 concerns, she continues to make tepache at home. Rafa has taken her place, but considers this his duty to ensure his wife gets the much deserved break from working. At $3 for a large cup packed with health benefits, we think it’s time Tepache made it’s way back into diets.

Photo Credit: @lisette_morales

From this Instagram post: “After my mom passed away, I took over her mini supermarket stall. It was a lot of responsibility at 9 years old, but I had to care for my family. Our stall was similar to the farmers market here in town except we didn’t pay rent. A wealthier man in town owned the land and allowed us to set up our stalls because he wanted people to better their lives. My business gave me a sense of purpose and helped care for my family

When I came to the U.S. in 1986, I let my business go. You needed a permit here. Things were different.

I started working in the packing houses packing every kind of vegetable that was in season. I eventually was able to work in other industries, but I had an accident at my last job that left me to take care of the home and garden.

I was my own boss in Haiti and I want my daughters to do the same. I have tried to instill the same mindset in my daughters because I know the value of being your own person and boss. (Moms name), a retired business owner who spends her time gardening and caring for her family.”

When I talked to her family and friends, many pointed to how Maria was someone who could talk to anyone, and who is as good at being interviewed as she is at interviewing others. (She's made a few TV appearances for her accomplishments and work throughout the years.)

Her own telling of why, though, was illuminating: “I feel like I often need to talk all the time in order to fill voids of space."

Maria’s parents always taught their children to value education, saying to Maria and her siblings, "If you don't want to labor out in the fields or in the sun like we had to, an education is what will lead you to better opportunities." But their migrant lifestyle made it difficult for Maria and her siblings to follow their parents' guidance. Curriculums between school districts were often different, meaning Maria and her siblings would have to repeat certain subjects or play catch-up in others. Making new friends was challenging, too.

Maria in elementary school

Still, Maria excelled in school; she won her school’s 4th and 5th grade spelling bees, appeared regularly in her school newsletters or on local TV, recited poems and speeches at assemblies and other public functions, and was elected class president.

Partially, doing well at school was a way to bury feelings at home. “I hid how sad I was when my parents separated,” Maria shared with me. “I wanted to keep a positive image of what my life was supposed to be like, and I struggled with depression. But instead of using other mechanisms to cope, like drugs, I just really excelled in school.”

Maria followed a steady model of academic success her whole life until she was about to enter college. She'd been accepted to the University of South Florida, but 10 days before move-in, while buying dorm essentials at Walmart with her mother, Maria received a call saying her offer was rescinded due to poor grades in her final semester of Early Admission, a program she participated in to take college-level classes as a high-schooler.

The moment was a huge heartbreak for Maria and, when she enrolled at another college, she sought to redeem herself, knowing she could do better. She also sought to remake herself and her Hispanic identity by joining a mostly-white sorority. “I internalized a lot of things,” she said. “There was always a comment about me being different, and how if you were different, that it was a negative thing."

Maria when she was at Florida Gulf Coast University

She recalled one instance with clarity. "A group of people and I went to the beach, and we saw these two Hispanic men dressed in blue jeans, a buttoned-up shirt, artisanal belts, and Mexican-style cowboy boots. They were taking photos of each other, and the group of people I was with made comments about how weird it was these men were wearing all this clothes to the beach.”

“I remember feeling uncomfortable, because I thought about how what they wore was similar to what my dad wore; the kind of day-to-day attire you'd see in Mexico. I knew these men were so excited to take photos to send back to their families. Many recently arrived immigrants may not visit the beach often so this was a major treat for them."

As much as she disliked moments like this, she hated feeling "different" even more. "I just wanted to be white," she admitted, "because I was tired of being the only person 'with a culture.' " She recalled how people would try to compliment her by saying, "Wow, you’re, like, the whitest brown person I know!"

Maria's actions stemmed from a mixture of shame, longing for acceptance, and outright survival. “As a first generation American,” she said, “we don't have really anything to fall back on. We don't have a safety net. So we're just kind of trying to get through life.” One of Maria's closest friends, Gin, who also grew up in Immokalee as the daughter of Haitian immigrants and was among the few other people of color in Maria's sorority, described her experience by saying, "As a minority, all you're trying to do is fit in. That's all you want. So you try to do what they do; dress how they dress; act how they act, so they don't see too much of the differences between you and them. And sometimes the jokes others would make, I'd have to pause and just be like, 'Am I really in this moment? Do they not see me?’”

Maria with Gin during a trip to Disney world

It took Maria living in other countries and being a part of other cultures to fully recognize the beauty of her own. After college, she traveled to Thailand to teach English and found acceptance among people as curious to learn about her culture as she was curious to learn about theirs. Next, she taught in the Dominican Republic, before joining a sorority sister to teach in the United Arab Emirates. Each move, she said, was a culture shock, but also an incredibly positive period of immersing herself within cultures she’d only read about before.

Maria in the Dominican Republic

Maria biking with her students in Thailand

A going-away book Maria’s students and other teachers made before she left Thailand

Maria in the UAE

"A lot of people told me I was brave to travel the world, and when they say that, I just think of my parents,” Maria said. “Because they really took a leap of faith. They jumped into the unknown. So me doing that stems from my parents' courage and hope for better opportunities.”

Life for couples does not stop just because it’s the week before their wedding; Maria and Yeison had little time and space for rest in the days before theirs. Maria currently lives with her cousin, Prisma, in a three-bedroom, one-bathroom mobile home 15 minutes away from downtown Immokalee. (Yeison visits almost every day, though before the wedding he lived in a separate apartment in Immokalee.) Frogs, geckos, birds, and plenty of bugs often appeared outside their home in the cooler hours of dawn or dusk; occasionally, they’d make it inside the home, too. Miles of farmland and marshes surrounded them, and because they chose not to pay for WiFi, they often contend with poor internet access when their cellular service is weak or drops entirely. They live with these inconveniences because the rent is far cheaper, and because they enjoy the feeling of being away from “civilization.”

Taken outside Maria and Yeison’s home

Farmlands near Maria and Yeison’s home

Both Yeison and Maria worked the full week before their wedding, Yeison as a social worker in Fort Myers visiting families to make sure children are in safe situations at home, and Maria as a community health worker going door to door around Immokalee to inform people about the pandemic and how to stay safe. On top of last-minute wedding planning, Maria was also dealing with some personal stresses as an advisor to her old sorority; the combination of work, the wedding, and issues with her sorority put Maria in a nervously energetic mood.

“Whenever she's stressed,” Yeison said to me one evening, “I try to stay calm, just to be able to help her out a little bit. She does the same for me when I'm stressed.” I asked more about their relationship, and particularly how they communicated. Their individual personalities struck me as being quite different, with Maria being very outgoing, talkative, and willing to say most of what was on her mind, and Yeison being far more reserved, soft-spoken, and visibly reflective. Most of their friends and family described the two as being "opposites" in their personalities.

Maria and Yeison during their ceremony

Maria answered first. “We’ve been doing a lot of self-reflection together about how we can best be there for one another, even though we’re so different. I need to talk and fill up space; I'm a people pleaser. And I had to learn that it's okay to be reflective, like Yeison is.”

Yeison followed, citing how it was less a matter of how much they said to one another, and more what they said to one another. “There was a time when I was accidentally hurting Maria because of failing to stick to commitments, like dates, because I'd be working late," he told me, "and before we talked about it, I didn't know how it was hurtful because her own father used to do the same thing, saying he'd be there or see her and then not show up."

Maria and Yeison on their wedding day

Other friends I talked to shared about how they'd seen the two grow together. Gin, Maria's friend from her college sorority, said, "Maria's been proactive about taking the time to figure out for herself: What is going on with me? Why am I triggered by certain things? And how can I prevent that from happening so it doesn't hurt the people that I love? She's made it a goal to better herself." Mike, Maria and Yeison's pastor and a close mentor to Yeison, said, "I remember seeing Maria encourage Yeison once when he had to teach something to the youth at church. She pulled him aside and told him to just breathe. And it was beautiful, seeing him fill up with the confidence he needed."

Yeison and Maria on their first anniversary of dating

Yeison spoke, too, of the two learning to communicate more about their individual traumas, and how they’ve helped one another process them. For Maria, Yeison has helped form a bedrock of emotional security as she worked through a period of depression early in their relationship. “My self esteem was low at the time and I doubted myself on everything,” Maria said. “We both worked on how to be there for each other and truly listen to one another, and his patience, tough love, and commitment to helping me improve in the gym translated to what I was struggling with in my personal life.”

For Yeison, Maria has helped to process the individual trauma of his past, and the uncertainty of planning a worthwhile and meaningful future. Yeison is a recipient of DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, a presidential memorandum issued in 2012 by former President Obama with the intent of temporarily protecting individuals brought into the US as children from deportation and granting them eligibility for work permits. While the legality of the policy was, and still is, vigorously debated, its impact on individuals like Yeison has been transformative.

Before DACA, and the opportunities for work and education it provided, Yeison hadn’t seen much of a future for his life. “Around my junior year of high school,” he told me, “I started to realize, my future’s field work. That’s it. That’s all.” When he graduated, he began that work. “You have these buckets for tomatoes,” he said, “and when they’re full, they’re 32 pounds. Every bucket you pick, you get $1, and you literally just do that all day, back and forth. It’s very draining being in the sun, and I remember feeling how that meant I wasn’t gonna have much energy to think about the future or anything else.”

I asked Yeison what his emotions were when he found out about DACA. “I was very happy, that's for sure,” he replied. “Because I was able to get a ‘normal’ job now.” A local non-profit helped him navigate the application process, and soon he was able to get his driver’s license and a work permit. His first jobs were mostly physical: working at a gym, as a lifeguard, and in yard work. Of the last, he noticed a similarity to how drained he’d been working in fields. “It wasn’t gonna really allow me to think much,” he said.

Yeison soon after he began seriously training at the gym

Yeison enjoys learning and making the time to reflect upon his life. He plays educational or motivational podcasts about communication and leadership on his drives to and from work, reads at home, and does his best to take full advantage of the opportunities afforded to him by DACA. He told me that attitude was a relatively recent change in his personality. “The first few years after DACA,” he said, “I realized I was kinda wandering aimlessly. I had no drive or motivation, and I needed to be smarter about the opportunities I had." He cut off certain people he considered to be bad influences, and began to actively try and change his lifestyle. "I would think twice before speaking, try to be positive, change up the music I listened to," he said. Yeison tried therapy as well. "It helped me to unpack some of the stuff I had going on, and it was difficult, being caught up in the past, not moving forward."

He added, "Glory to God. That's for sure."

The stories I write for this project aren’t just about couples; they’re also for them. Along with photos, stories are among our strongest links to people and to the past. Just as I expect a couple will show their wedding photos to their children and grandchildren, so I expect they’ll share these stories, too.

Because of that, I’ll ask couples what parts of their story they hope shine through; what to emphasize or to treat with particular care or caution. Assembling stories about our lives is a valuable but ultimately arbitrary process. The memories and experiences we choose to become the record of our lives are just that: choices. We are in control of the story we tell ourselves and to others, and there is so much power in that simple realization.

When I asked Yeison whether there was anything he felt was core to his story, he had a quick answer: “Could you make sure you emphasize the importance of faith in my life, and in me and Maria’s relationship?”

Maria and Yeison praying together at their ceremony

Yeison never grew up attending church. His parents weren’t religious, and Sundays were far more likely spent at home while his dad worked in lawn-care than spent at a church listening to sermons. Only later, a few years after he graduated from high school, did Yeison take an interest in faith.

His original intentions weren’t entirely pure. “I was about 21, and there was a girl I was interested in who would go to church,” he admitted to me. Yeison began attending as well, and amid his romantic pursuit, he also found something else: relief from his loneliness, and from the disjointed traumas in his life. “I didn't really understand it," he said, "but listening to sermons and the music made me emotional." The words he heard in church began to work on his emotions, giving him a different, more empowering way to think about his life and his loneliness.

This first religious nudge ended when the girl he chased didn't reciprocate his feelings, but a close friend's encouragement soon pulled him back. “She gave me this book,” Yeison told me, “that basically tells about the love of God, and how you don't need anyone to love you as long as you have God in your life.” His friend’s action made Yeison ready to accept an invitation to attend church from a man named Mike, now Yeison’s pastor but then just someone he helped to train at the gym.

Mike and Yeison during the wedding ceremony

At church, Yeison found a small but incredibly supportive community of other men whom he could look up to as role models. “Little by little, I was just building a relationship with God and with Christ,” he told me. “I gave my life to Christ seven months after Mike invited me to church, and Jesus Christ became the ultimate mentor for me. His words and concepts make sense to me; ‘Love thy neighbor’ is something I think about each and everyday, and the holy words were the only cure to my resentment and anger.”

Yeison with some of the other members of his men’s small group from church

That same church, coincidentally, had been Maria’s own childhood church. Unlike Yeison, Maria had grown up around Christianity. She was raised Catholic by her father’s prodding, but later ventured towards a local Baptist branch after her parents divorced. College became a dry period for her faith—“There was a women's Bible study that I went to occasionally, but I definitely got more into the whole partying culture and doing whatever I wanted,” she told me—but her time abroad in Thailand drew her back. “I was very fortunate to have friends who were abroad who still practiced their faith, and we’d hold Bible studies together.”

Maria had originally planned to spend more time working internationally, but personal matters brought her back to the US in early 2018. Some of her family members I talked with told me how they saw a stark change in Maria's personality when she returned; her energetic, talkative, and outgoing self had turned far more reserved and quiet.

When I asked whether she agreed with others' observations, Maria said, “I struggled a lot with anxiety and depression when I came back.” She’d imagined herself being a globetrotter after college before then settling down to work at a major company in a big city. Instead, she was "back where she started," which, at the time, felt like failure.

In retrospect, returning to Immokalee changed Maria's life for far better. “I bumped into Yeison one day as he was leaving his house after years of not seeing each other,” Maria said. “He was riding his bike to work, and we walked only a little bit before we had to go different directions. It was really crazy how I literally found him along the way.” Yeison soon reconnected with Maria and her family, and offered to help train her at the gym.

Yeison and Maria with friends before they’d started dating

Both told me that they initially clashed. "When I got back from being abroad, I felt like I was shut down a lot in my previous job,” Maria said. “So I didn't have a lot of confidence in myself. I'd think, 'I can't do it,' and so I wouldn't even try." At the gym, Maria felt Yeison was just being unreasonable, pushing her far past her physical limits. But Yeison saw through to something far deeper. "Maria would tell me, 'You shouldn't push me to do more than I can, when you know I can't do it.' And once, I just told her, 'Why do you always make excuses for everything in your life? Why don't you even try?'" Maria was initially furious, but soon realized the truth in his words. "I was in a place where I felt it was better to not try, than to fail and have someone be upset at you."

Yeison’s words stayed with Maria; so did his demeanor, which Maria noticed was different than when they were growing up. “I noticed there was a change in him, and I was very curious about it,” she said. Yeison invited her to church, and Maria began to see the source of Yeison’s change. “It really just attracted me back to the church,” she said, “because I saw the change that was happening in Yeison, the love that he had for God. And I was like, oh my gosh, I remember when I used to have that type of faith, that type of love for Jesus, too.”

Maria and Yeison in front of their church in Immokalee

They began dating half a year later, in August of 2018, and initially kept their relationship a secret. “It was two or three weeks before we told anyone we were dating, because we thought they wouldn’t believe us or would find it weird,” Maria said, laughing. Her hunch was right; her old brother, with whom Yeison was friends from high school, joked to Yeison, “I can’t believe he didn't tell me anything! You’re my friend! And you’re dating my sister!” The rest of the family shared similar reactions, though they were all happy to see two people whom they cared so deeply about in a relationship.

As Maria and Yeison learned more about each others’ pasts and insecurities, they each supported the other’s efforts to grow from them. Maria helped Yeison plan a surprise birthday trip to Texas to meet much of his family from Mexico, who traveled to meet him for the first time in over two decades. “We learned so much about Yeison’s younger years,” Maria recalled. “We got to hear stories about his mom, and got to know his immediate family much better.” It was the first birthday Yeison celebrated surrounded by his biological family since he’d left Mexico as a six year old.

Yeison reuniting with his sister, grandmother, aunts and uncles

Yeison with his younger sister

Both had clear ideas about the direction of their relationship. “I didn't really date in college or even after college,” Maria said, “because I always had very high standards for myself. I didn't want to waste my time on something that wasn't going to be long-term worthwhile.” Yeison felt similarly. “I kinda had flings before, but after a while that was getting old, and when we started dating, I definitely could see her as my wife, for her morals and the type of woman she is.” The two were engaged a year and four months after they began dating, around Christmas of 2019, at the church that brought them together.

“He proposed in front of our entire church,” Maria said with some embarrassment. “We were doing a women's church Christmas celebration in a side room, and there was a booth to take pictures. I had just finished praying for us, and remember the youth coming in, and then the men coming in, and I was like, 'Why are they all here?' Because the women weren’t finished yet, but they said they were doing family pictures for social media. Someone said that Yeison and I should get a picture, so we went up to the front, and then Yeison got down on one knee and proposed.”

Yeison’s surprise proposal at church

Maria laughed. “But it was just so loud around us that I said, ‘What?’” She gently rolled her eyes and smiled at Yeison, who sat nearby as we talked. “Because he talks very lightly. And then the whole church was just staring at us, and it was even more awkward.”

Maria and Yeison had imagined saving money for a year to be able to pay for a large traditional Mexican wedding and to invite family from Mexico, but the pandemic, of course, spoiled those dreams. In its place, though, appeared a chance to be more intimate with their guests and to worry less about keeping specific appearances. On the morning of the wedding, I drove first to Naples, where two of Maria's younger sisters, Laura and Sylvia, work at a beauty salon. The two sisters helped everyone else with their hair and makeup and, in her moments of rest, Maria worked to tweak the final touches on her and Yeison's vows; she'd written them entirely in Spanish.

They read:

“Yeison, te amo porque me has enseñado a poner a Dios primero en todo las situaciones, buenas o malas. Me cuidas aunque a veces sea muy difícil, normalmente porque tengo hambre o no soy una persona que le gusta levantarse en la mañana. Aunque no me voy a levantar a las seis de la mañana a hacer ejercicio, prometo siempre enseñar gracia, amarte inmensamente, y siempre estar ahí. Aunque nuestra primera cita fue un paseo de bicicletas de seis millas, yo se que nuestro amor y apoyo va ayudar en cualquier situación que parezca igualmente difícil. Tu eres mi mejor amigo, mi protector, y mi pareja para siempre. Nuestras diferencias son lo que amo mas de nosotros. Enseña que Dios nos ha hecho único y perfecto para cada uno. Estoy muy agradecida de que seas mío.”

In English:

Yeison, I love you because you have taught me to put God first in all situations, good or bad. You take care of me even though it is sometimes very difficult, usually because I am hungry or I am not a person who likes to get up in the morning. Even though I'm not getting up at six in the morning to exercise, I promise to always teach grace, love you immensely, and always be there. Although our first date was a six mile bike ride, I know our love and support will help in any situation that seems equally difficult. You are my best friend, my protector, and my partner forever. Our differences are what I love the most about us. It teaches that God has made us unique and perfect for each other. I am very grateful that you are mine.

Maria writing her vows

Sylvia helping her older sister Bianca with her makeup

Almost everyone in attendance at the wedding were from Maria's immediate family. None of Yeison's family was able to attend; his father was away on an emergency work trip, and the rest of his family was stuck in Mexico because of travel restrictions. Maria had thus been adamant Yeison invite whoever he wanted to, even as they narrowed their guest list. He chose a few family friends who’d known him since he was a child and other members of his church.

After dinner, we all gathered outside to participate in La Vibora de la Mar, or Sea Snake Dance, where Maria and Yeison, each held in place by a trusted friend or family member, stood on chairs and made an arch with Maria’s veil. Their other guests then held hands to form a chain of bodies that turned and twisted as they ran around the courtyard and between the newlyweds.

Maria and Yeison getting ready for La Vibora de la Mar

I thought of how this tradition, usually performed by hundreds of guests, felt different when performed by only a dozen; how the former reflected culture through its scale, a noisy, chaotic display of tradition that even those who didn’t know the origins could appreciate; how the latter reflected culture through the act itself, a display of individual choices to participate in this small but meaningful custom; and how Maria and Yeison’s whole wedding represented this symbolic question of what it means to share culture at a smaller scale. That they chose, still, to uphold their traditions amid the pandemic and with a fraction of their original guest list showed just how much they valued those traditions.

I watched and smiled as I observed, even in this moment, Maria and Yeison displaying their personalities; Maria, from her perch on the chair, hollered directions and waved shier relatives or friends to join in the fun, while Yeison stood quietly behind her, smiling and laughing but also clearly hesitant to draw more attention his way.

Maria and Yeison performing la vibora de la mar

When we caught up a few weeks after their wedding, I learned that while the logistics of their relationship had changed (Yeison officially moved in with Maria, making their home just a bit more crowded, and Maria recently returned to work in education) their emotions, they claimed, had not. The two still attend church regularly throughout the week and on Sundays, Maria still loves to help people throughout her community, and both continue to feel grateful for the life they’ve been blessed with living.

But when I talked to Prisma, Maria's cousin and their roommate, I learned Maria and Yeison might have changed more than they were letting on. "Yeison used to be so quiet when he was here," she told me, "but now that he lives here and they're married, it’s so different. He's way more talkative, and way less shy." She wondered aloud if perhaps he felt embarrassed when he visited before marriage. "He goes straight to playing with my baby daughter now, picks her right up, or goes outside and just plays baseball with my son. And he never used to do that, so I'm like, what the heck??" Yeison, it seemed, finally felt emotionally home.

Yeison and Maria with Prisma’s baby daughter

Prisma, Maria, and Yeison at the wedding

Most of Maria and Yeison’s energy right now is directed towards becoming financially stable. "The big picture for me is getting a better job to make sure I can provide, and charting how to get there," Yeison told me. "I need to be a little more strategic, and a little smarter." He's currently studying to get his Commercial Driver’s License so he can drive semi-trucks, which will pay better than the social work he currently does. Long-term, he hopes to utilize more of his mind in his work by becoming a mechanic for commercial vehicles.

Maria, for her financial part, is a master at finding cheap deals—much of her closet, though it looks expensive, is purchased at Goodwill—and, as the eldest sister of her family, feels a particular responsibility to provide for not only herself but also her parents and younger siblings. "It's really hard," she said, "when you know your immigrant family doesn't have much money to fall back on." She plans to continue teaching and using her storytelling platform to include other cultures, and hopes to one day write a book about the diverse community and history of Immokalee.

Maria and Yeison with her family

Both also want kids, but not for a few more years. "People have advised us to just kind of enjoy ourselves as a couple first, which we want, too," Maria said." When the time comes, they hope to raise them in the same supportive atmosphere as Maria experienced among her church community and family growing up, and for their kids to avoid the scarcity they had to live through.

Immokalee has been home for Maria and Yeison for most of their lives, but they'd enjoy living somewhere else, too. Maria, who’s already spent years abroad, is more open to the idea of just picking up and moving somewhere, while Yeison, perhaps because of the uncertainty from his past, prefers to first become financially secure before taking on the risk of moving. "We want to move eventually," Yeison said, "but we also make sure that we can both have our goals and needs met.”

"She knows I’ll support her, though, whatever it is that she decides to do,” he told me, smiling. “I'm trying to learn not to be as pessimistic.” He added, softly, “I feel like my mom's always watching over me. And because of that, everything always seems to work out, regardless of the situation."