A pair of queer, Christian women connect over their love for making music, and create harmony at the intersection of their faiths and identities.

Megan + Sherell // Cambria, California

Megan and Sherell, who met in 2019 and were married on July 17th, 2021 in Cambria, California, took communion, performed a foot washing, and prayed at their wedding.

Megan and Sherell’s wedding ceremony

Their ceremony began at 3pm when the harsh afternoon sun fell past its peak, its rays softening and warming their 70 friends and family who stood in a yellowed field in front of a California Live Oak tree. A faint, even sound of rolling waves came from the nearby ocean and a gentle wind whispered through the great tree’s branches while a friend of theirs strummed a guitar and sang Elvis’ Can’t Help Falling in Love. Sherell walked with her grandmother from a clearing behind the tree; Megan came from the front, stepping down the aisle with her brother by her side and her sister holding her dress from behind. She gave both a hug before standing to face Sherell.

Photos from the start of Megan and Sherell’s ceremony

"We are gathered here, surrounded by the beauty of creation, nurtured by the sights and sounds of nature, and blessed by the love of Jesus, to celebrate Sherell and Megan,” Emily, Sherell’s best friend, began. “To know these two is a real gift. Sherell is one of the best humans with the biggest smile and the kindest heart. She is a force to be reckoned with, and a friend to confide in. She's a blessing, believes in the unseen, and fights for those she loves.”

Sherell and Megan’s wedding ceremony

Emily looked towards Megan. “Megan is simply the best. She is steady and calm, and brings peace to the chaos with her unwavering strength. She calls people to a higher standard just by being around them. She calls us to be gentle, humble, and kind.”

A passing car, seeing the ceremony, honked six times in quick succession. Megan and Sherell turned to look at it, squinting their eyes and raising their eyebrows. Their guests looked at the car and then at them, unsure whether they would be angry. Megan let out an exasperated “Thank you,” but laughed and waved as she did. Sherell grinned too, and shook her head. (They’d been forced last-minute to change their ceremony’s location from its original spot, an isolated cliff-side bluff. The field and tree were beautiful, but also next to an overpass.)

Sherell and Megan’s wedding ceremony

“Megan pulls out the best of us without even really trying, just by being herself,” Emily continued, smiling at the line’s timeliness. “Together, they honor Jesus with their goodness, and they live to bring the kingdom of heaven right here, right now.” She looked at Megan and Sherell. “As I look around, I see the faces that make up your inner circle. The people who are to hope with you, to support you, to be proud of you, and to remind you that love isn't the happily ever after, but the experience of writing your story. Relationships, milestones, both big and small; quiet moments that belong to just the two of you; and moments like this, ones you choose to share with the people you love the most.”

Emily asked Sherell and Megan’s pastor and friend, a man named Jason who leads a queer-affirming church in San Luis Obispo, California and whose husband also joined in the audience, to pray. "Loving God, we’re gathered to celebrate Your gift of love and its presence among us today. We rejoice that Megan and Sherell have chosen to commit themselves to a life of loving faithfulness to one another. We praise You, oh God, for the ways You have touched our lives with a variety of loving relationships. We give thanks that we have experienced Your love through the life-giving love of Jesus Christ, and through the care and affection of other people.”

“We ask for Your blessing in the marriage of Sherell and Megan, Your beloved daughters. Remind them always of Your great love for them, a great love that brought them here to this day, and a great love that surrounds them. Remind them that they are Your beloved, and our beloved also. And lastly, gracious God, remind them in times of joy, and in times of challenge, of the covenant promises that they make with each other."

Megan and Sherell’s wedding ceremony

Pastor Jason reached for a basket of small pieces of bread and a glass of grape juice. “Megan and Sherell asked to have communion as part of their ceremony today,” he explained. “Communion is a reminder of the final meal that Jesus had with his very close disciples nearly 2000 years ago. It's a meal that celebrates God's unconditional, extraordinary love for all of His children. We remember that on the night in which Jesus gave himself up, He took the bread, and He blessed it, broke it, and shared it with His beloved disciples, the people He loved the most. He said, ‘Take and eat this, all of you. This is the bread of life. You will need this to remain strong.’”

“Likewise, after supper, he took the cup, blessed it, and shared it with his friends, saying, ‘Take and drink this, all of you. This is the cup of the new covenant.’ A new promise that God will be the God of everyone and everything. There is no one now excluded.” Megan and Sherell each took communion, and then pastor Jason invited anyone who wanted to partake to come up, too.

Megan, Sherell, and their guests taking communion

He directed everyone’s attention to a small bucket and a pitcher of water off to the side. The Christian significance of foot-washing, like that of communion, comes from Jesus’ actions at the last supper. After he and his 12 disciples ate, Jesus rose from the table and, without explanation, began to wash the others’ feet. The act is now interpreted as one of humility and service; someone in Jesus’ position would have never been expected to wash the feet of those he guided, and yet he did.

“There will be times when you may stand and rejoice in each other’s triumphs,” Pastor Jason continued. “You may also be drawn closer together in sadness and defeat. Show unwavering support.” He gestured towards the bucket. “By washing each others’ feet, you are saying, ‘I’m kneeling before you, humbly accepting you as you are, not only with my words but also my actions. My love is unconditional.’ You commit yourselves to each other today as equals.”

Megan and Sherell’s foot washing ceremony

Each night before dinner during the week I spent with Megan and Sherell, Megan prayed for us. Her prayers were short, but earnest, and equal parts gratitude and supplication. She gave thanks that I could join her and Sherell in their home; asked that their minds be filled with peace and rest amid the chaos of the wedding; hoped for their friends to have a safe journey to the wedding; expressed thanks when they did.

Faith has always been a cornerstone in Megan and Sherell’s lives, from their childhoods to their relationship to how they think about the future. Normally, it offers them peace or guidance when they feel fear or doubt. Amid wedding planning, it had also been a source of anxiety. "Maybe you've encountered this working with other same-sex couples before," Sherell said to me, "but it's difficult because both of our families are very evangelical Christian. And so we literally called specific people in our families to ask, ‘Do you want to come to our wedding? ’” A few answered that they did; many others said they didn’t. Most of Sherell’s immediate family would be absent, while Megan’s parents would be present but wouldn’t participate in certain traditions, like walking Megan down the aisle.

Megan and Sherell were disappointed, of course, that some of their family didn’t support their marriage. Mostly, though, they were in high spirits. The silver lining to certain people not attending was that it guaranteed those present genuinely loved and supported them. "We're really excited to get all our friends together, people we've always known would get along but haven't met,” Sherell said. The two have day jobs (Megan in graphic design, Sherell in real estate) but their passion is music—writing, singing, performing it throughout California, usually at wineries or artist showcases—and many of their wedding guests were musicians, too.

That music is important to Megan and Sherell is obvious by a quick glance around their home, which fills with signs of a musical life: instruments (two guitars, a keyboard, a harmony drum, and a violin tucked under their bed), accessories (amps, cables, speakers, sheet music), and decorations (a keyring holder shaped like a miniature Marshall guitar amp and a large painted metal treble clef.)

Megan and Sherell’s home

Both grew up in musical families. Many of Sherell’s earliest memories are of watching her father perform with her church’s worship team. “I was maybe five or six years old, and I was just glued to his guitar playing and singing,” she told me. Her parents took notice, and put her into piano lessons in elementary school, violin in middle and high school (with guitar on the side), and singing for as long as she can remember.

She always had a unique voice. “It was a bit lower than most women I knew, and it made me feel a bit awkward,” Sherell said. “And so I remember just singing to myself all the time; close the door to my room, get out my guitar and pretend I was on a stage singing all passionately.” She started performing towards the end of high school. “Music was just the place where everything made sense to me,” she said. “I had a secret dream of being a rock star, but I'd never tell anybody that because it was impractical, and so I kind of had this vision of living this epic life and doing whatever I wanted and traveling the world."

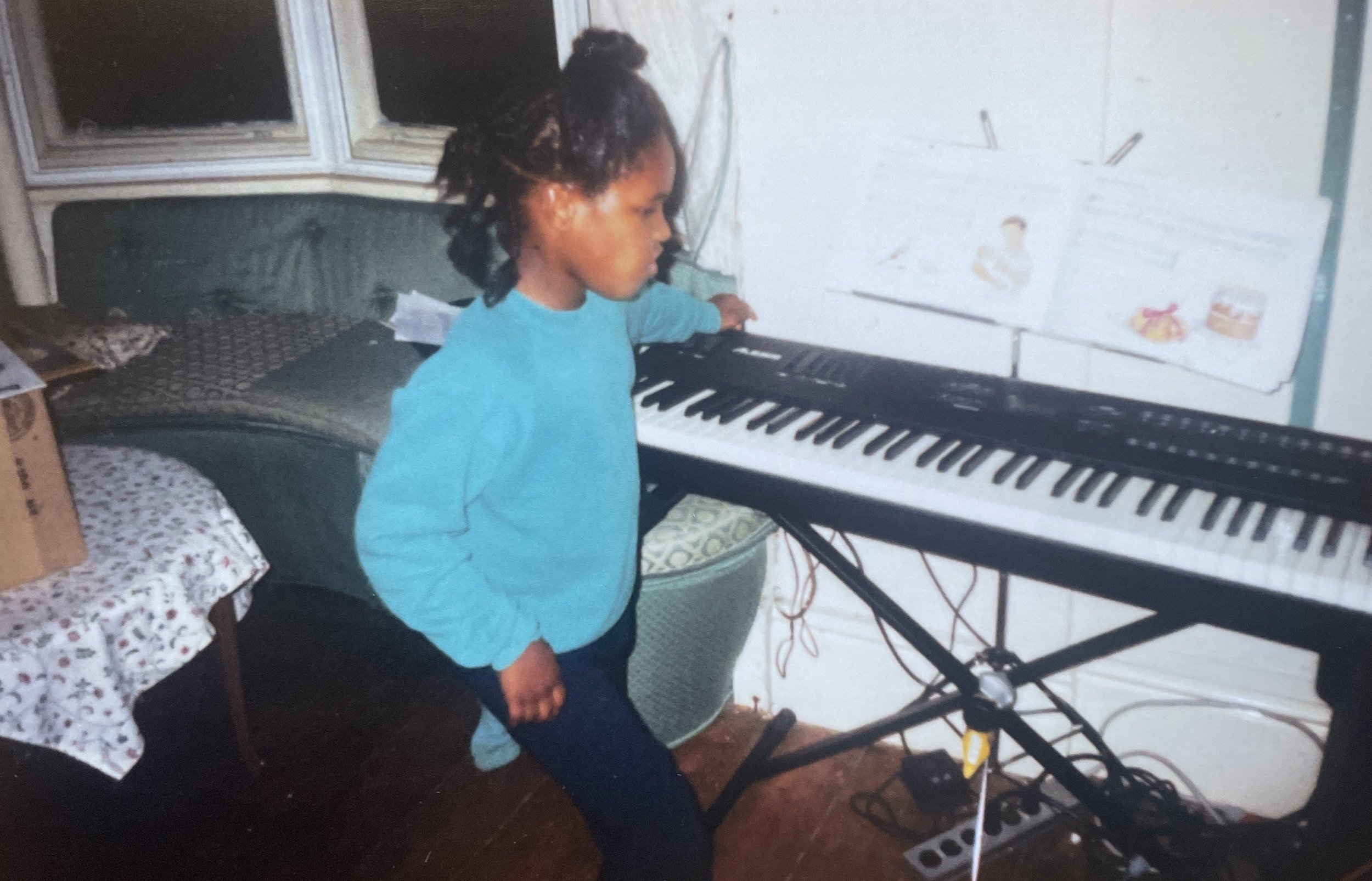

Sherell learning piano while living in England

Sherell as a teenager

Megan came from similar musical roots. Her mother played the harp, her father the classical guitar, her brother trombone, and her sister sang. Her parents put her in classical piano lessons, and Megan taught herself to sing and play guitar. By the end of high school, she’d recorded her first song and performed at open mics, but wasn’t yet sure whether to make music her path. “I had this whole conflict before college of wondering if I should do something to grow my music, or if I should just do something practical,” she said. “Because music doesn’t make much money, and I also wasn’t very good at singing and songwriting yet, even though I really liked it.”

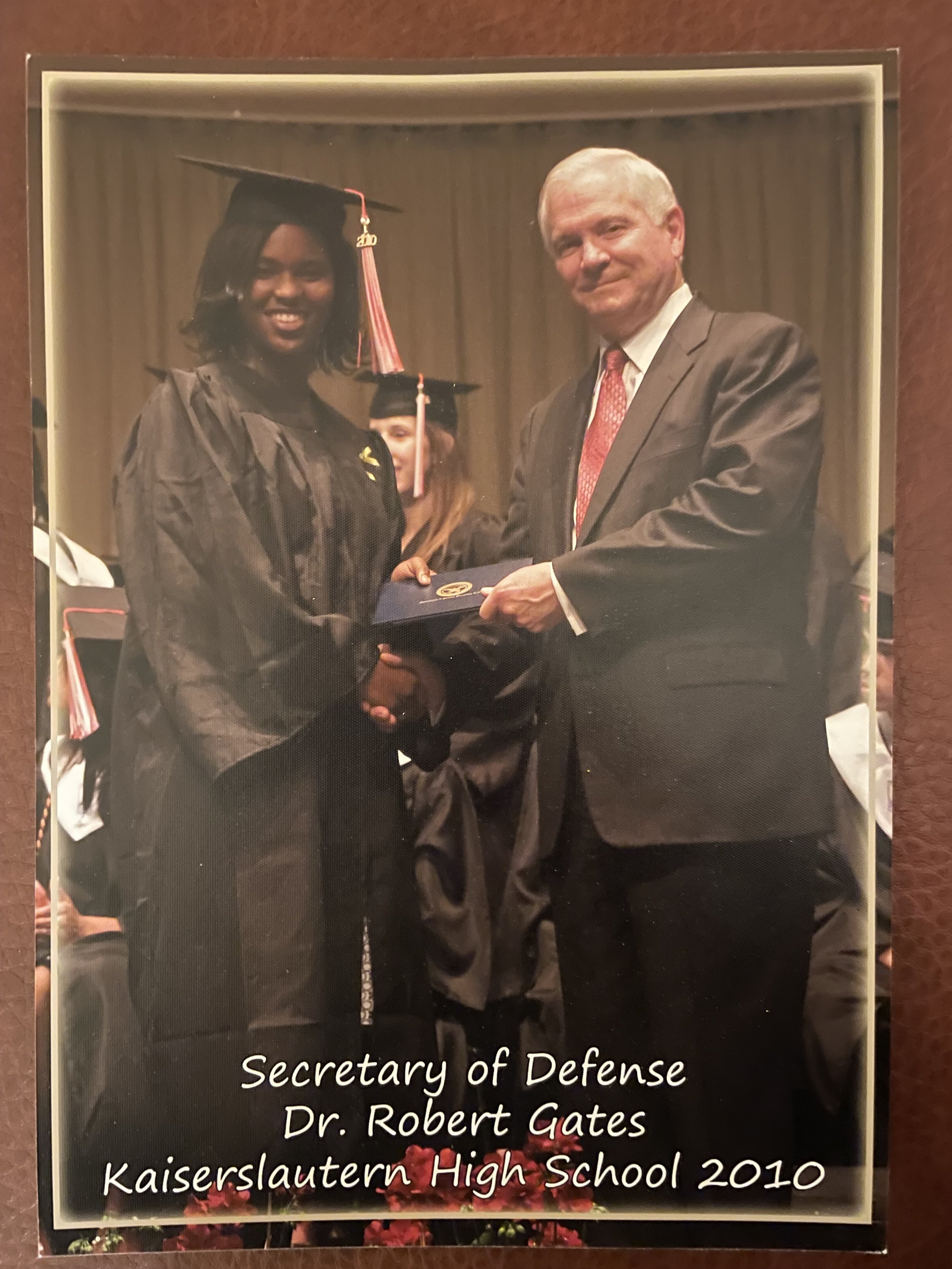

Megan at her high school graduation

She chose to be practical by studying Graphic Communication in college, but continued to nurture music at open mics and showcases. The summer after her third year in college, she made it a goal to play as many gigs as possible. She emailed dozens of wineries in the area (there are almost 100 in San Luis Obispo County alone) and quickly filled her whole summer weekend schedule.

Megan playing at gigs

Sherell had already heard about Megan before they met. "We were both gigging, playing music mostly at wineries," she said, "and I kept hearing Megan's name and, honestly, was kind of annoyed." Who was this Megan woman, Sherell wondered, and why was she always playing the same gigs Sherell wanted to play, too?

They finally met at a singer-songwriter showcase for artists in the California Central Coast, hosted at a small restaurant in Arroyo Grande on March 13th, 2019. “I was with another friend,” Sherell said, “and as I performed, I saw this girl sitting at a table by herself with, like, a cardigan on, drinking tea in a room full of people drinking beer and wine. And my friend and I just thought that was kinda interesting.” Sherell performed first, playing a cover of Lego House by Ed Sheeran and her own original songs. Her style was “punk-rock acoustic,” with a voice that carries her whole body’s momentum in high notes and her life’s story in low.

Sherell singing at home

Megan performed after, playing one of her own songs called Everywhere You Go. Sherell froze. “I was just like, how did that voice come out of that girl?” Megan’s style was “jazzy pop,” and though her speaking voice is light and feathery, her singing voice is like what the color burgundy would sound like: deep, rich, and yet bright under the right light.

Megan singing the night she and Sherell met

Megan had noticed Sherell and her friend looking at her before and during her performance. When she finished playing, she walked to their table to say hi. Sherell invited Megan to join them at another bar that was hosting an open mic night. To Sherell's surprise, Megan accepted. "People here in California say ‘Let's hang out! ’ and it just, like, doesn't happen," Sherell joked. Megan explained, “I was kind of longing for deeper friendships at that point, and I sensed a good vibe from them, so I just said, ‘Okay! ’”

After the open mic, Sherell and her friend invited Megan to hang out more at Sherell’s home. Again, Megan agreed. They watched A Star is Born, and Sherell claimed the seat on the couch next to Megan. "It felt like it was a fast, genuine friendship,” Megan said. They stayed up late talking after the movie and when Megan eventually went home, Sherell found that she'd left a ring on the living room table. "I did not do that on purpose," Megan claimed. Sherell countered, laughing. "This is totally what girls do when they want to see you again! They just leave their things behind."

The two were magnetic friends. Megan went on a tour in LA for a few weeks after she and Sherell met, and when she returned, they became inseparable. “If I wasn’t at her house, she was at mine, and we became central to each other’s daily lives and routines,” Sherell said. "What was different for me about Megan was I hit it off with her, like, immediately, and I didn't feel like I had to hide anything. Our conversations were easy, and it felt like we constantly had fun.”

Megan and Sherell on their first date

Sherell remembers clearly the moment she fell in love with Megan, at brunch on Easter Sunday of 2019, about a month after they first met. Megan was booked to play at the restaurant the entire afternoon. Sherell, along with Megan’s friends and family, had reserved a table to support her. “It was one of the best days of my life,” Sherell recalled. “I met her whole community: her parents, her sister, her roommates, and it was amazing. I remember just talking to everybody and feeling completely welcome."

Halfway through the brunch, Megan began playing the opening arpeggios to Regina Spektor’s Us. Sherell paused her conversations and turned to watch Megan. “It sounds so cheesy,” she said, “but Megan was playing, and singing, and looking at me, staring at me. And I just saw where I wanted to be and who I wanted to be next to for the rest of my life."

Megan singing at brunch on Easter Sunday 2019

"And then I thought, Oh, shit. I've fallen in love with a straight girl."

Sherell had wondered before if someone could love her in the way she loved them; to love all of her. She was born in Phoenix, Arizona, on March 30th, 1992, and immediately entered the foster care system, which she stayed in until she was four years old. "The system was trash," she recalled, "with some people having foster kids because they got checks for them. I remember being in some pretty abusive homes."

In 1972, a bit over a decade before Sherell was born, the National Association of Black Social Workers issued a formal statement against Trans-racial adoptions. The statement’s opening read that the organization, “has taken vehement stand against the placement of Black children in white homes for any reason. We affirm the inviolable position of Black children in Black families where they belong physically, psychologically and culturally in order that they receive the total sense of themselves and develop a sound projection of their future.”

The statement influenced the policies of many adoption agencies around the country. Many became hesitant to allow white families to adopt Black children. Sherell's parents petitioned their agency in Arizona for an exception, and won. They adopted Sherell in 1996, when she was four years old.

Sherell (center) with her family the day she was adopted

I asked if, at that age, Sherell remembered what was really happening. "Oh, I was very aware of what was happening around me," she replied immediately. "I’d met my parents once before, and then the agency told me one morning that I was getting adopted by them. And I remember walking into the room and seeing, like, a sea of white people smiling at me with tears in their eyes." Sherell's parents already had three biological children. Sherell was the second child, and oldest, they adopted, after her brother Phil and before her sister Moesha. (All three adopted children were Black.)

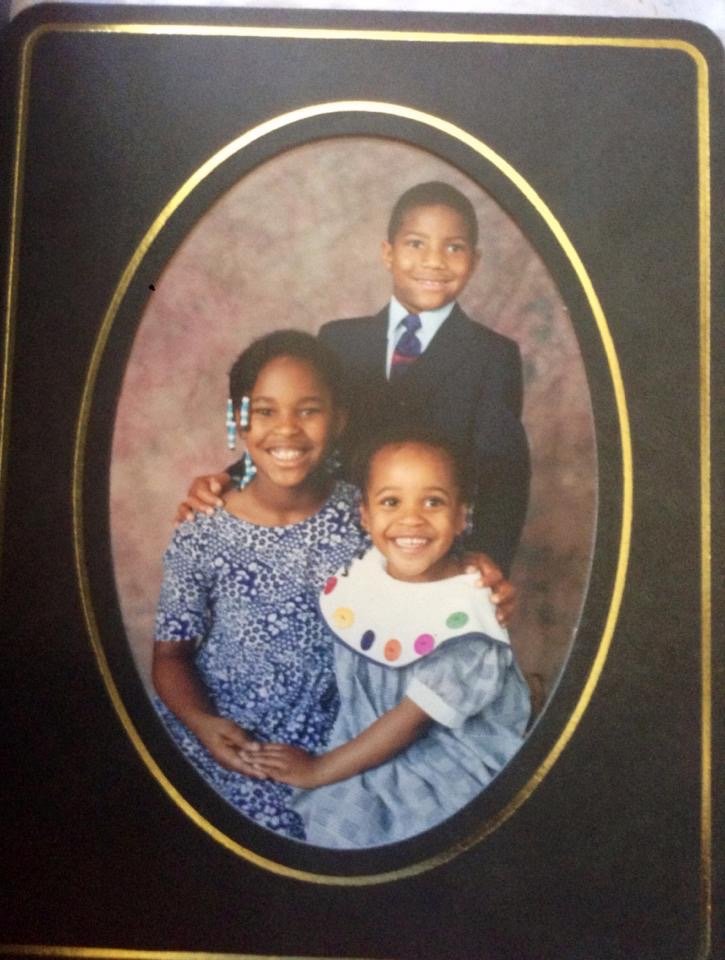

Sherell (left) with her siblings when she was five years old

Regardless of her first impressions, Sherell’s transition into the family, she told me, was quick and pragmatic. "One of the ways they established me into the family was to give me my own chores,” she said, “and that was cool because all my other siblings had their own chores, too, and their own ways of belonging to the family. I felt like I was quickly a part of that, within the first days and weeks.” She remembers her father reading bedtime stories to all the children on their couch, teasing and being teased by her brother, Phil, about not being able to swim (and then promptly winning against him after she learned), and her older sister, Tory, gifting her a small ring soon after Sherell joined the family.

Sherell (bottom right) with all of her siblings

The family was very close, in part due to their frequent moves for their father’s work as an officer in the Air Force. Sherell’s family moved to England for four years a few months after she was adopted, then back to the US for four, and then Germany for all of Sherell’s time in high school. "We learned to be super intentional with family and friends,” she said, "and that distance didn't make a difference for those you loved."

Sherell (center) with her family

Sherell's family never lived on-base. "My parents wanted us to grow up with an understanding of other cultures around us," she told me, "so we grew up in villages and neighborhoods, and even though we were home-schooled, we played tons of sports with both the military kids and the local community." She never felt spoiled, but recognizes certain privileges. "I remember realizing how amazing it was that we could travel for, like, an hour and get breakfast in France, then come back to Germany and continue on with the rest of our day."

Her parents did their best to show the world to Sherell and her siblings, not just have them read about it. They learned about the glories and crimes of the English monarchy, visited Native Americans on their lands in Utah, toured civil rights museums in Alabama, stood where the Berlin Wall and Dachau gas chambers once stood in Germany. “My parents gave me and my siblings a respect for and deep understanding of the cultures and the histories we were around,” Sherell said. “I wouldn’t be who I am today or view the world the same way if they hadn’t taught, encouraged, and pushed me to sit with the discomfort of the new or the painful.”

Sherell (center) with her siblings

Undergirding all these experiences were clear values. “I’d say my parents were pretty fundamentalist Christians," Sherell said, “and placed their faith above all else.” She went to church multiple times a week to babysit, lead bible studies, or attend youth groups. “We weren't sheltered by any means, but they did want us to grow up with their Christian values and a Christian perspective about science; not wanting us to think too much about evolution, or the big bang theory, or that sex before marriage was okay."

Sherell (second from the right) with her mother and siblings

She shared all of this with a nostalgic tone, the way someone might recall good memories with an ex after a bad breakup. She spoke of feeling lucky. "I remember growing up around other foster kids, looking ahead at the older kids, and seeing how their circumstances were sometimes so limited. And I didn't want that. So I felt like I hit the jackpot getting adopted, because I got to grow up and literally see the world. I’m very grateful for my upbringing.” She spoke of conflict. "But I was obviously still wrestling internally with my identity. I'm a Black kid in a white family; I'm an American and growing up in Europe; I'm queer growing up in a fundamentalist Christian family."

She recalled her parents explaining their rationale to the judge in allowing them to adopt Sherell. "Their argument was that they weren't going to raise me Black or white, but Christian. And now as a full-grown woman, I'm like, so you mean white." She had few connection points to her own Black identity, and fewer people she could talk to about it. "Most of my childhood, I think I felt a little bit out of place around Black people, because I wasn't raised around them,” Sherell said. “I didn't have Black culture, eat Black food, listen to Black music. So I kind of felt like an imposter."

Sherell (blue) with her siblings

She remembers small, mostly benign comments that nevertheless scarred her over time, like thousands of tiny pinpricks. "My other Black siblings and I got comments about how strong we were, or how fast we were, or how white our teeth were. Which made me feel weird as a kid, though I think that was the extent of my awareness at the time of what was going on."

Her own family didn’t say these things, but she still, at times, felt out of place. “I didn’t have the language yet to describe my experiences, couldn’t explain why certain comments felt off, even when coming from people who genuinely loved me,” she said. That language has only come in retrospect. “There was a narrative that said that as a young Black kid, my experiences, abilities, and opportunities were no different from the young white kids I was raised with or around. And that’s simply not possible.” Colorblindness, in the name of inclusion, in fact made Sherell feel minimized.

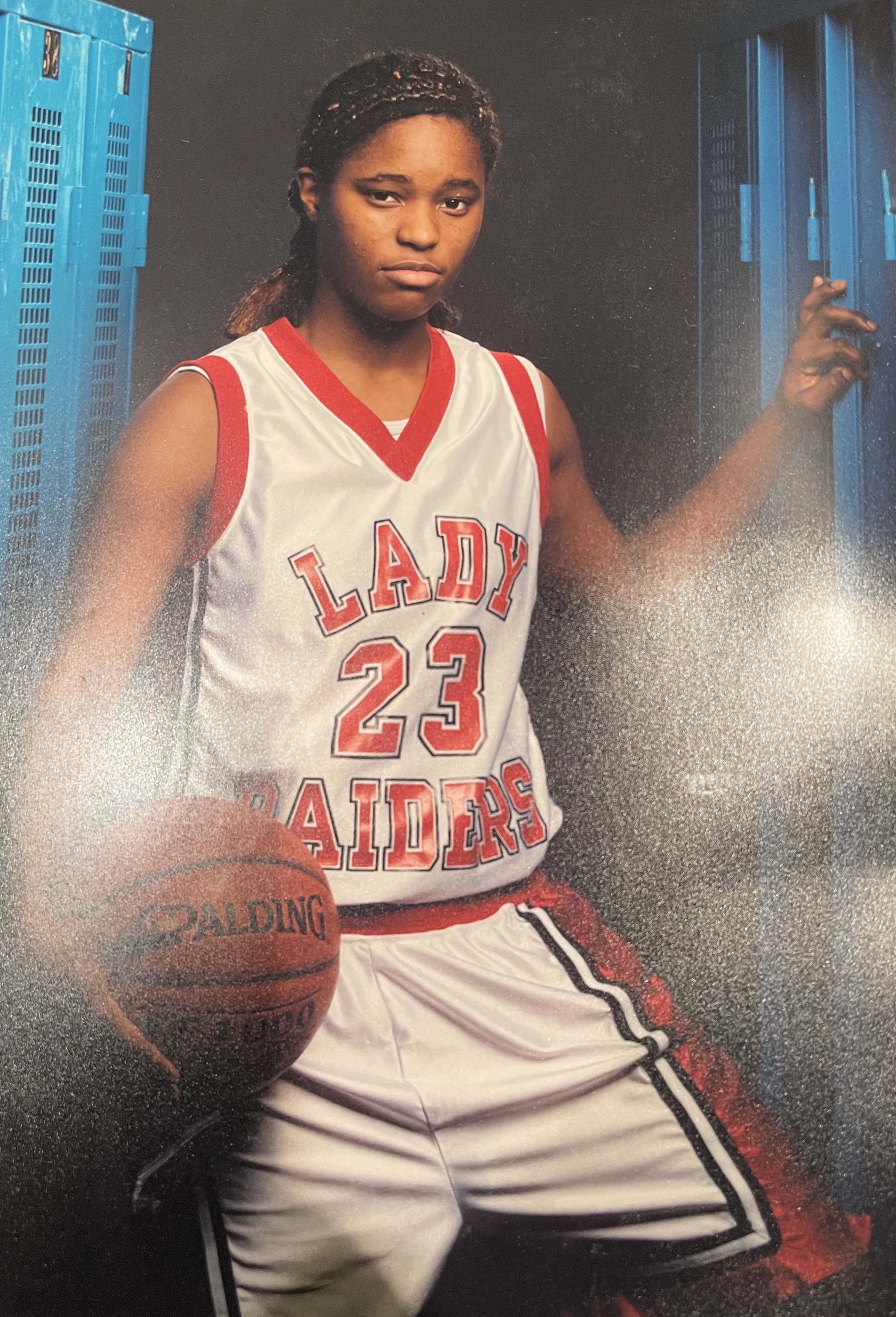

Sherell in high school

She went on. “On the one hand, my parents didn’t leave us with excuses. My dad taught me I was capable of doing anything I put my mind to, regardless of set-backs or struggles. On the other hand, my siblings don’t have PTSD or OCD from their childhood. My white siblings didn’t have to prove their competence out the gate from childhood into their 30s like I did, or live with a standard of excellence at all times just to be considered equal. Excellence was assumed for them, and I felt like for me, it had to be proven, and many times I came up short.”

Complicating her understanding of race was an even deeper conflict that, unlike her skin color, no one else could see. "I've known I was queer since I was, like, seven,” she said, smirking and adding, “I, like, made out with my best friend at a sleepover. I was pretty smooth." She was attracted to girls, but also had crushes on boys, and without knowledge of the word “bisexual,” her self-conception anchored to Christian verbiage. "The Christian world teaches you to doubt your feelings," she said. "Don't trust your heart, because everything is a temptation. And so for me, as a bisexual woman, it was basically, ‘Oh that part of you that's attracted to women is the temptation, the thing you need to ignore. Just fall for guys.’"

Sherell grew up in the purity movement, which served as a convenient mask for her true feelings and emotions. "Basically, the movement was about kissing dating goodbye, save yourself until you're married, give your purity ring to your husband only on your wedding night. And I fully embraced it, because I was queer, and it was my attempt to rid myself of my deep shame. It made it easy to just say that I was super spiritual, and not dating anybody, when really it was because the people I wanted to date were women."

Sherell at her high school graduation

After high school, Sherell returned to the US. She enrolled at a local community college near home to be with her mother and younger siblings while their father was away on deployment, and studied theology with the intention of becoming a youth pastor.

College had other plans. "It was the first time in my life that I'd met out-of-the-closet queer Christians," she said, pausing for a few seconds. "Honestly, it fucked me up. Because I thought my life was gonna be this certain way, where I repressed all these things and lived this epic single life. And now these people were showing me that something different was possible. And I didn't know if I was ready to figure all of that out."

Sherell with friends in college

She went on. "It was honestly triggering for me to be around these other queer Christians, because they were some of my best friends in the world. They were serving people, and they were Christian. It wasn't a walk in the park for them; it was costing them to live the way they were living. But they were so free, some of these most loving, generous, beautiful humans I'd ever met. And I became depressed, because now that I knew that life was possible, I had to deal with the things I had repressed. I had to accept the costs of living out who I really was."

She went on. "My faith was my anchor, maybe even from before I was adopted, and so I just got so angry at God. I was like, ‘How could you make me queer, and then have all these problems with it, and then not change me? You're a jerk. I don't want to serve you.’" She stopped going to college, failed out, and descended into a spiral of depression and self-harm.

As with many others who grow up in cultures that teach views or beliefs opposite their own identities, Sherell's depression didn’t just stem from the difficult process of reconciling her identities internally, but also from the knowledge that reconciling them externally would cost something important. "For my family, and the culture that I grew up in, that duality of being queer and Christian wasn't possible," she said. "And I knew that if and when I'd come out publicly, I'd do that at the cost of my family. And my family was my whole world."

She went on. "This depression lasted about a year, and in the middle of it, I remember sitting on the floor with a knife to my wrist in the kitchen when nobody was home. And I just remember having this out of body experience where I was able to see myself for a moment with clarity and say, ‘How did I get here?’ How did I go from loving life so much, to here?" She found the strength to ask for help, and told her brother everything. “He's like this six foot three, three hundred pound Black football player,” she said, “a tough, bulky guy. And he broke down and started weeping, and he hugged me, and said, ‘You're not alone.’"

Sherell with her younger brother, Phil

Soon, she had told all of her family. "I don't remember saying much other than, ‘I'm bisexual and Christian, I don't know what to do with that, and I want to kill myself.’" Her family, she said, rallied around her, and though their intentions were supportive, their solutions were beyond unhelpful. "Everyone sort of treated me with kid gloves," she said. "I was sent to this horrible counselor who was a pastor, who just sat there and talked for our entire sessions as I just pretended to listen and nod. It was, like, the worst therapy session ever."

After a few months at home, Sherell decided that she needed to go out and live life to discover two things: who she really was, and how much God loved her. She joined a Christian nonprofit that focused on youth outreach and mentorship in Pismo Beach, about three hours from home. It was one of the best and worst experiences she could have had at the time. On the one hand, she did discover more of herself, and how much God loved her. On the other, that process was traumatic in its own way.

Sherell in her early 20’s

Sherell, in her words, hadn’t yet come out to anyone in a “true” sense. “I told others that I was attracted to women, that I couldn’t repress it anymore, and I didn’t know what that meant for me. But I hadn’t told them that from a place of acceptance. I told them from a place of defeat.” She fell in love and began dating another woman while working at the nonprofit. When the organization found out, they told her to break up, or leave. "I was living off of financial support from my church and community back home," Sherell said, "and so if I suddenly left, they'd all ask why. And the org would have told them why."

Regardless, Sherell’s decades bottling her repression meant she couldn’t continue her work anymore. She faced three options: quit outright, and risk being outed; carry on, and risk mental breakdown and worse; or step away for some time, with the option to return if she someday wanted to. She chose the last option. “You can only repress things for so long before your body and mind pay for it. I think leaving saved my life.”

Sherell while on sabbatical

For a year, she separated herself from ministry. She got into real therapy and, as she said, "that was the most transformative year of my life.” She played music and worked at a coffee shop, making friends who loved and supported her throughout the year. “I began to see a Jesus kind of love in a more tangible way than I had in a long time,” she told me. “I didn’t feel like we were concerned about answering these big life questions for each other, but just loving each other through the process. They held space for me, celebrated, and sat with me.”

She described feeling God nudging her to learn more about theology and sexuality, both for her own benefit and also for others’. “I’d kept my sabbatical journey pretty private,” she said, “Yet so many Christians started coming out to me, people reaching out asking me how to best love the queer people in their lives, well-known queer people in the area that I was just suddenly running into.”

For the first time in her life, she validated her own experiences. “I sat and watched how the majority of Christian churches had been responding to the LGBTQ community and hurting them and how that differed so much from the healing, safe spaces my dear friends were creating for me that year,” she said. “I sat with the ever-increasing ambiguity of scripture about all this. And I sat with Jesus and what I knew about the voice and the heart of the God that I loved, for a year.” She learned to reconcile her faith and embrace her sexuality. “It became so clear: I am bisexual. That is not a surprise to God, because I was created that way and God said I was good. I learned that there was a plan filled with life and abundance and thriving for me and for every queer person.”

Sherell with her friends, including her matron of honor at the wedding

She continued. “I went through a very long and traumatic reconciliation with all of this, and the silver lining is I'm pretty strong now, and have a lot of resources from that time.” Two books were especially helpful: the first was Walking the Bridgeless Canyon: Repairing the Breach Between the Church and the LGBT Community, by Kathy Baldoc, a straight conservative evangelical Christian who took it upon herself to research the historical and social context of Christian discrimination against LGBTQ+ people. The second was James Brownson’s Bible, Gender, Sexuality: Reframing the Church's Debate on Same-Sex Relationships, which takes a more scriptural approach to examining same-sex relationships.

“I didn’t really like books that told me where I needed to land,” Sherell said. “I wanted ones that would just give me more information so that I could think for myself. And these books, learning about biblical and historical context, along with the actual stories of queer Christian kids and their actual experiences, along with what I know about the heart of God, along with my own story, shifted me to this place of healing; to thinking about what is the most healing and thriving story that God could possibly have for a queer person.”

Among the most taxing arguments she’s heard from others is that she chose to do all of this because it benefited her life; because she wanted to be selfish or to justify her actions. “I explicitly didn’t want to be affirming,” she said with a clear huff in her voice, “because I knew the ramifications of that. I knew that I’d lose my family. I knew what would happen if I actually changed my mind and lived out who I was and my beliefs. And I still chose to seek that truth. How is that selfish?”

Music paralleled all of this growth. She played for herself more than for anyone else. “I stepped away from anything public, deleted all my social media,” she said. “I didn’t know what I had to bring to any kind of stage, so I just decided I was gonna play for myself and figure out who I was.” She began to write again, inspired by her experiences and others’. “I started writing about stories that weren’t my own stories, that I hadn’t lived, but things that I’d want to experience.” She wrote about mental health, depression, being rescued. “I wrote my songs for me, but every time I wrote, I also knew it would be touching somebody else.” She healed, emotionally and physically. “I was just doing music as a solo artist, learning to be this gorgeous, out, Black woman.”

Sherell performing

She never formally "left" many of her communities—her church at home, for example—but over time, she became distanced. "I was just around so many non-affirming Christians after I came out, and had such a passion for creating a space where queer Christians could gather and show non-affirming fundamentalist Christians that we were possible, that I just thought, screw it; I no longer have a desire to serve in this space. Which was a big deal, because I'd grown up my whole life serving in churches, helping build churches. I kind of left church but kept my faith, and though I have zero desire to do ministry at all, I'm still hardcore Christian."

These memories bounced in Sherell’s mind at Easter brunch in 2019, when she realized she loved Megan. She wondered to herself if she were about to subject herself to all of the pain again of loving someone who wouldn’t love her back, though Sherell had her hunches. "I'm like, this girl is very obviously queer," Sherell said, smiling at Megan sitting next to her, and who blanched in embarrassment, "and I made it very clear I was queer and Christian."

Megan explained her embarrassment. "When I meet new people, I'm like, super friendly, bubbly, whatever. So for a long time, I thought it was just that with Sherell." She turned towards her. "But I do feel like looking back, I was kind of, like, flirting with you." She pointed to her phone. "I can show the texts I sent, and how they were kind of how I would act if I was nervous." After they first met, they began hanging out every week; Megan introduced Sherell to her college roommates and family; then, they were hanging out every day.

Sherell saw a budding relationship; Megan saw a budding friendship. "It'd been a few months after we met," Megan said, "and Sherell was hanging out late with me and my roommates. And at some point, I just told her, ‘You can just crash here in my bed.’ And I don't even know what was going on in my brain, but in the moment I was thinking, ‘Oh, when my sister comes to visit, she just crashes in my bed, so what's the issue?’ I think my Christian upbringing brain was just creating all these scenarios where this was acceptable."

She told me about how it was easy, for a time, to ignore labeling her actions as romantic. "I'd always liked boys growing up," Megan said, "and I wasn't even allowed to have boys in my room. But there weren't any rules about that with girls, and so I never really thought about it as something I should be nervous or embarrassed about. I thought we were just best friends.” Sherell looked towards Megan with skepticism. "We were!” Megan insisted. “But also, I was crashing at her place, and she was waking up when I needed to go to school, making me coffee and breakfast before I left, doing all the regular things people do if they’re dating, too. But I didn’t see it that way."

Sherell, at this point, had to jump in. "She was throwing maddening signals," she said. "We were, like, watching TV in my house with her roommates, and I was laying there because of a back injury with a blanket over me. And we'd be sitting next to each other, and she'd be like, rubbing my leg underneath the blanket." Megan disagreed. "No I wasn't!" Sherell stood her ground. "Yes, you were." Megan conceded a bit. "Maybe I had a hand on your leg." Sherell took the minor victory. "I was like, this girl definitely likes me."

The confusing signals went on. One evening, Megan asked Sherell for her thoughts about the next Valentine’s day. "If both of us are still single, we should do something together," Megan told Sherell. "So, you want to go on a date together on Valentine's day?” Sherell replied. "As friends, yes," Megan said. "No, you’re saying you want to go on a date with me on Valentine's day, right?" Sherell insisted. Megan paused to think. "Yeah, I guess I'm down."

In the moment, Sherell didn't say much else. "I didn't take the offer, because I was just too nervous," Sherell said. "My friends were like, ‘Sherell, don't fall for a straight girl.’ And I was like, 'But look at all this evidence! She definitely likes me.’" Sherell's friends weren't convinced; it was clear to them that either Megan was stringing Sherell along or she was totally unsure about herself, neither of which would lead anywhere positive.

The next day, Sherell called Megan, and told her her feelings. Romantic feelings. “I like you,” Sherell said. “And I like what we’ve been doing.” Megan paused over the phone.

"Thanks for telling me,” she finally said. “But I just don’t really see myself that way, and I don’t think I like you in that way.”

Sherell shared her own story of self-love and affirmation with the practiced tone that a motivational speaker has when they talk about their story. It’d been close to a decade since she first began to question, and then reconcile, her own identities, and her narrative arc felt well-established. But Megan, just a few years removed from those emotions when we first talked, was visibly diffident. She told me about her inner thoughts after her call with Sherell. "When Sherell said she liked me as more than a friend, I think I was like, ‘Thanks for telling me...’" she paused. “It was weird. I think I was just struggling with seeing myself as anything other than straight, because that's how I identified my whole life."

After Sherell shared her feelings, and Megan responded with uncertainty, Sherell asked for a bit of space. Megan, confused, called her younger sister, Rachel, for advice. (Rachel had come out to their family as bisexual a few years earlier.) “I don’t think I like Sherell like that, but I also don’t like the space,” Megan said. “Maybe you’re gay for Sherell, then,” Rachel replied. “Maybe Sherell is special.”

Megan thought about it. “I’m… not really sure.” Rachel tried a more direct tack. “Okay… then do you want to kiss her face?” Megan paused. “Maybe… possibly…”

Communication froze for a few days. Eventually, Megan and Sherell met for a walk around a lake. "I like you," Megan recalls saying to Sherell, "And I don't know what that means… And when you say you like me, I also don't know what that means… I'm not ready to date… But I also don't really want you to date anyone else… But you can if you want… But I don't really want you to… And I might not be ready today, or anytime soon, and you don't have to wait… And I don't really want you to wait, because that's too much pressure. But also..." Sherell smiled. "And I remember just stopping and having this smile on my face the whole time because you were saying a bunch of words, but all I heard was, ‘I like you, and we're gonna be together.’"

For some people, love comes first by way of the mind: it is analytical, premeditated, deliberate. For Megan, love came first by way of the heart: emotional, spontaneous, exciting yet nerve-racking. "I was kind of going full speed with my heart," Megan said, "thinking this is where I wanted to be. And then I was also like, I need to make sense of this in my brain before I try and explain it to my mom and dad."

“Nobody would guess that I would be with a girl,” Megan continued. “I’d identified as straight my whole life, dated only guys. So I was like, this is gonna be like earth-shattering for everybody. And even though my heart was already there, and it was obvious Sherell and I were together and dating and loved each other, my mind would also trip me up because of everything I’d been taught growing up.”

"I don't really know what I am," she added. Her confusion, to me, showed how rigorous our social vocabulary can be in defining identity. Language is the home to story and expression, and just as different languages have different words that defy translation, so some people’s upbringing’s provide them with a language that fails to translate their full selves.

In the words she knew, Megan told me this. "I guess I would say I'm bi now, but my whole life until two years ago and meeting Sherell, I'd only ever had crushes on men. And also, there was the baggage of having been raised with the Christian belief that the Bible said homosexuality is a sin, and thus not ‘inheriting the kingdom of heaven.’" She described an internal homophobia and its contradictions with supposed external acceptance. "I was raised that if you found out someone was gay, you'd just keep on being really loving to them but that you couldn't accept their sexuality. Which is weird and confusing now, because how can you really love someone or celebrate them without loving or celebrating all of them?"

Megan was born in San Jose, California to a life she described as stable and calm. Her entire life was lived in the same home. Her mother worked as a civil engineer before becoming a homemaker, and her father worked as an IT professional for a private Catholic high school in nearby Mountain View. She recalled little, perhaps even no, fighting or harsh disciplining in her childhood. "Everything was pretty peaceful," she said.

Megan (second from the right) with her family

Megan’s parents were easy going ("I secretly wish they forced me to start doing something like dance or sports, because I think I might have been good at it," she told me) and as long as Megan did her best, they accepted the results. "I mostly just wanted to get good grades for myself," she recalled, "and I never felt a ton of pressure from them."

Both of her parents attended California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, located along California’s Central coast halfway between Los Angeles and San Fransisco. Megan followed. She had a range of skills—music, art, math, writing—that spanned creative and technical thinking, and chose to study graphic communication, like graphic design but with a less art-based focus that would allow her to be creative while also being practical.

Megan (center) with her siblings

She also joined a ministry on campus. "Before college, I'd been helping lead some bible studies,” Megan said. “And so I did that in college because I felt they were good things to do, and a good way to find meaning outside of school and my friends.” Conversation about faith permeated her childhood like water through a sponge: ideas about kindness, self control, fruits of the Holy Spirit, gratitude, and prayer were foundational in her household. Her family attended church each Sunday at a nondenominational campus with traditional values but nothing “too extreme," as Megan put it, and her parents instead stressed a personal connection with God rather than one bound solely in a church. “We'd go to church consistently, but the churches we went to were kind of big, and so it was always hard to, like, find my group of people there.”

Megan (left) with her college roommates

Megan told me that her and her family’s story would seem straightforward and uncomplicated—they long fit well into a clean, Christian arc of expectations—before it began to deviate in the form of her own sister telling her parents she was bisexua in 2017. "My family and the church we went to kind of just treated the solution as doing your best to be with the opposite sex, and to be celibate from the same sex," Megan recalled. "So she came out with a sort of understanding that she wouldn't date girls."

I talked to her sister, Rachel, one afternoon about all of this. Even though she was a few years younger than Megan, she had experienced and wrestled with similar feelings for longer. Many of her words reminded me of how Sherell had described her own experiences. "We didn't really grow up with examples of, like, Christian people who were cool with someone being gay, too," Rachel said. "We had no idea how to answer questions like ‘What do queer Christian people do? How do they live? How are they happy? What do they do when they realize they're queer?’ Because they just didn't seem to exist." (The closest example they had was an extended family member who was openly gay, but non-affirming, meaning they didn’t accept their own sexuality as proper and healthy.)

Megan with her sister, Rachel

Rachel continued. "I had queer friends in high school, but I couldn't talk to them about Christianity, and I had Christian friends but I couldn’t talk to them about queerness. There was no one at this intersection, or at least no one who was openly there, to talk about this shame I was dealing with, this internalized homophobia."

Megan asked many of the same questions after she met Sherell. She graduated college a few months after they met, and transitioned a part-time job she had in school to full-time work. Sherell’s home had a small but cheap extra room, and Megan moved into it. She spent almost all her time in Sherell’s room. “Anytime my parents would come visit, we’d have to make my room look like I actually lived there,” Megan said. “I’d mess my room up a little and throw some clothes on the ground, while Sherell put half a glass of water on the nightstand and plug my phone in. And then my mom would arrive and I wouldn’t even know how to turn certain things on.” Her parents, at this point, still thought of her and Sherell as great friends, and not more.

As Megan worked through her own heart and mind, she asked Sherell to be patient with her, a request she knew carried weight. “It was a weird spot,” Megan said, “because I needed to take some more time to figure out how to tell my parents about us. But that meant that Sherell was sort of being put back into the closet with me. She was already fully out for years, totally fine being queer. But with me, she had to pretend to a lot of people that we were just great friends, for six months.”

Sherell sighed. “It wasn’t fun. Being in the closet. Again.” Her friends had questioned her rationale. “Are you sure you want to do this?” they asked. And although Sherell could have justifiably answered ‘No’, she also felt a conviction that the time Megan spent in reflection would lead somewhere meaningful. “She was my best friend, first and foremost, and I knew first hand how intense and life-changing this process could be,” Sherell said. “I told her many times that in the end, no matter where she landed for herself, I’d be there for her. And in my heart I knew that if we did get through this together as a couple, then I’d found my wife.”

She recalled her own caution giving Megan too much advice. “I oftentimes had a hard time sharing resources with Megan,” Sherell said, “because I didn’t want to do it to be like, trying to change her mind about something so we could date.” She sighed. “There's a horrible idea we both grew up with about how the devil will, like, persuade you into something that looks good, and people claiming that’s the devil tempting you. And it’s such a toxic, evangelical theology, because it doesn't allow for people to think for themselves, to grow in their faith. It implies that everything is already decided as good or bad, and there’s nothing to dig deeper for, nothing else to do other than follow the rules.”

I asked if she saw parallels in her story and Megan’s. “For sure,” Sherell replied. “But in a lot of ways, she was going through certain things I wasn’t, like her thinking she was straight and then having feelings for a woman out of nowhere. She was also going through things at a way faster pace than I had to, which makes her one of the bravest people I’ve ever met.” Megan added, “In some ways, it was probably easier for me to go faster, because I didn’t have to struggle with a certain part of my identity. Sure, I had to figure out how to explain it. But I also knew for a fact that I was with Sherell, and I loved her. That wasn’t ever in question.”

Megan has always been a rule-follower. “I’ve always been a goody-two-shoes,” she said. “Almost never got disciplined, always had good grades, never got into trouble. And so this was, like, the only time that I’ve been terrified to say something to my parents. Andd it took so much time to figure that out.” Much of that, she said, was hoping that her parents knew Sherell on a personal level—knew her character and heart—before she introduced her as a partner, and not just a friend. “I didn’t want them to make any assumptions that Sherell was someone who influenced me in a bad way,” Megan said, “or pressured me to date her or anything like that.”

Megan and Sherell with Megan’s parents

In October 2019, six months after she and Sherell began dating, Megan told her parents the truth. She asked them to a restaurant, and shared everything: that Sherell was her best friend, and more; that they’d been dating for six months; that they were living together; that she had experienced indescribable pain and invalidation but also indescribable joy being in love with Sherell; that she believed God brought them together; that her faith had changed; that she still believed in God; that God still loved her. “I was just saying one thing after another, telling them everything, laying it all on the table,” Megan said. Her parents were shocked but, in the moment, replied in simple, supportive terms: “Thanks for telling us. That was so brave, and we love you.”

A few days later, her parents asked to visit again. “We’ve been taking some time to process everything,” they’d told Megan, “And we're going to come back to talk to you about everything again.” Their biggest concern, Megan said, was that Megan had felt she’d needed to keep the relationship a secret for so many months, and that she hadn’t felt safe to talk to them sooner, to come to them for counsel or help finding counsel. “I think deep down they were troubled by the same-sex relationship, but they were also worried that saying so might distance my relationship with them,” Megan said. “So they also said they were very concerned that Sherell and I were living together before marriage, since that also wasn’t part of our Christian morals.”

It was near Thanksgiving, and Megan’s parents issued a tacit invitation. “They said something along the lines of, ‘It’d probably just be best if only you came,’” Megan said. Her uncle had just passed away, and her parents cited that they wanted to just have family there so they could remember and memorialize him. Megan and Sherell viewed it as a passive way to say Sherell wasn’t invited. (Sherell doesn’t hold it against them, necessarily. “Megan loves her family, and I knew they’d probably be my family one day, too. So loving Megan meant loving and being patient with her family. They were grieving many things, one of them being the story they wrote in their minds for their daughter, and I understood that.”)

Rachel, Megan’s sister, told me more about her and Megan’s relationship with their parents. “I’ve never doubted that our parents love us,” she said. “I still don’t doubt that; they really, really do love us.” She shifted to talking about her own experiences. “And I think sometimes that perhaps makes it harder, because it’s not like I can just write them off. I do want them to understand me more, because I know they really want to be there for me and Megan.” She laughed softly, and added, “and they’re really good at, like, parent stuff; doing taxes, telling us how to buy a car.” Megan agreed with this, and noted that their family still loved spending time together. “My family has been like, ‘Okay, let’s spend time together, regardless of whatever we might be going through theologically,’” she said. “It was really hard, but now it’s kind of, like, patching up relationships.”

Megan with her parents

Megan share all of this without the frame of her “coming out.” To her, it was simply the story of her life and of her and Sherell’s relationship. “Sherell grew up with all these thoughts of identity and shame, whereas I grew up my whole life in my Christian household thinking I was straight,” Megan said. “And I think that there are so many journalists or TV shows or portrayals of queer people that are like, ‘Here’s this person, and they’re gay, they came out when they were this age,’ Where they make it the thing that makes someone important and special. And I don’t like that; more and more people coming out and it being less and less special would be great.”

As the world stopped in March of 2020, Megan and Sherell’s relationship grew. Sherell was the first to suggest marriage. “I feel like Sherell has more of a leader personality,” Megan said, “and that she’s been clear about where she was going in life, while I was always either catching up to the same ideas or naturally coming alongside them.” Sherell agreed. “I wanted to be very clear the entire time that I wasn’t playing around. I wasn’t here for experimenting. I could see us going somewhere, and I wanted to make Megan very clear that she could join in that or that this was also her opportunity for an out if she didn’t want that.”

She went on. “I think that marriage is the commitment to keep choosing another person for the rest of your life, no matter what comes. And I wanted that with her; for her to be the person I chose every day, no matter what versions of her she changes into or what version of me I change into. No matter what life throws at us.” She also talked of practical and philosophical reasons for marrying. “Our society gives so many privileges and perks to be married; taxes, double incomes, hospital rights. And it’s almost like the last step of validation in a relationship, because so many people, for so many years, couldn’t get legally married. And so it’s spiritual, and it’s also practical, and it’s also validating.”

Sherell turned to Megan. “Did you ever see yourself married to me before I brought it up?” Megan thought about it, and replied, “I think my whole life I knew I wanted to be married, to fall in love, to have my best friend, my forever person,” she said. “But I was always kind of like, hands open to the sky, whatever comes my way. It was never like, ‘This is what it’s gonna look like.’” She paused. “Which probably helped me eventually be open to what did come my way. ” She noted the beauty of the spiritual side of marriage, too. “Coming together under God with a priest, your whole family and community being present with you in that moment. It’s encouraging, thinking of the presence of God uniting you as two people.”

Sherell’s proposal in July of 2020 was elaborate and, to Megan, touching. It began, as many surprise proposals do, with a false premise: Rachel, Megan’s younger sister, needed to take a set of beachside photos for a gig, and wanted Megan to come with her (and dress up too, in case she also wanted to take photos.) Unbeknownst to Megan, Sherell had spent the past few weeks coordinating with all of their close friends to be involved. Each held a single white rose and stood interspersed around a bluff overlooking the beach. As Megan passed each, they handed her the rose, said, “You are so loved,” and walked away.

Megan had a full bouquet when she walked up to Sherell, who stood near the edge of the bluff, overlooking the ocean. She, too, held a white rose, as well as a small blue box.

Sherell’s proposal to Megan. Credit: Michelle Harrell

Half a year later, Megan proposed in return. Hers would be more private. She suggested a sunrise hike, which Sherell thought was just a cute, spontaneous date. When they neared the hill’s peak, Megan feigned forgetfulness in the form of coffee left in their car. “I’ll be right back, you go ahead to the top,” she told Sherell.

Sherell sat at the top of the hill admiring the rising sun. She heard Megan panting back up the hill, and when she turned to look at her, she saw Megan holding a bouquet of chocolate strawberries and roses, and a small wooden box. “You’ve had a long journey to finding love and acceptance in your life,” Megan began, “and you deserve the absolute best.” Sherell had begun to cry. “And, I think you agree that’s me.” Megan laughed. “So, will you marry me?”

Megan’s proposal to Sherell

Like other couples quarantining together, the pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 were full of growth, arguments, and just a bit of fun. “We were at the peak of the BLM movement after George Floyd’s murder, and I had no idea of the gaps in my knowledge of history and white privilege until I met Sherell, this beautiful and amazing Black woman who challenged me in every way,” Megan said. “I learned how to love and respect her better, and how I really had some of my own ignorance unveiled.”

Saving for their wedding was also a challenge. “Neither of our families were going to pitch in to help pay for it,” Megan said, “and since we’d already had a period of both of us being unemployed for a few months, we decided to get on a strict budget to be able to save up. We had a lot of arguments about spending and saving, living a fun life versus being boring.” Sherell added, “It just gave us more opportunities to look each other in the eye, take a deep breath, and come together to figure things out.”

Fun meant spending time together: baking bread, making music, creating dates at home when they couldn’t leave. “We had this dance party in our living room,” Megan said, “got colorful lights, dressed up in ‘club attire.’” Sherell made cocktails, and Megan compiled a playlist of pop songs from Ed Sheeran, Demi Lovato, and Fifth Harmony. “It was so much fun,” she said.

“I sometimes couldn’t see past my own two feet, but I knew I was walking in the right direction,” Megan said about thinking of her and Sherell’s future. “It wasn’t always about seeing the future or marriage or our being together long-term, but I just knew this is right, you know? Like, I didn’t see it turning out any other way.” They are content with accepting, in their words, “Whatever God puts on our hearts.” “Listening for and hearing God’s voice is a huge part of my story and how I live,” Sherell said. “Stopping and waiting for God to speak and help make decisions.” Megan added, “I have moments where I have a feeling, and Sherell will say, ‘That’s the Holy Spirit, God’s voice,’ and later on it just becomes obvious that God was pushing us in one direction or another.”

Each still values their faith, but it’s also changed. “Church feels more joyful now, and less fearful,” Megan said, though she also admitted that they’ve stopped going each Sunday to focus on their own personal relationships with God instead. “For me personally, I love Jesus, and have a relationship with Him,” Sherell said. “And I believe that I’m specifically created and designed to bring good and healing and love into the world through the things He’s given me.”

Her version of Christianity is one of universal love. “This good God I’ve walked next to my whole life from foster care to now; this Being I’ve misunderstood at times, raged at, cried with, and who has kept me alive and held my hand through all of it? That God names every single human, ‘Beloved ’,” Sherell said. “It’s not about our silly little dangerous rules we put on each other or bury ourselves with. From beginning to end, my faith is about this enduring and limitless love we’ve all been swept into, this hopeful fight for a full and good life for every human, and this deep peace that I carry within myself now and bring into our community and this marriage.”

Megan’s views mirror Sherell’s. “I think my faith is very similar to what I used to believe, but without any fear,” she said. “I don’t believe that hell exists. In the end, God’s kingdom is filled with the goodness of everyone, despite humanity’s flaws and darkness. God loves everybody equally. Some people just don’t know that, see that, or oppress others because they don’t realize that everyone is created and loved by God.”

Professionally, they’d like to pursue music full-time while building the financial foundations for themselves and their future generations. They’d like to be artists who play, record, and tour with their own music, and help others to do the same. “One of our big goals in the next couple of years is to launch our own record label that focuses on independent, undiscovered artists and teaches them how to master their own career,” Sherell said. Megan would love to have her own marketing department in the label, drawing on her design experience to help artists organize their brand and provide infrastructure for them to perform and grow as musicians.

They see their musical careers ebbing and flowing with one another. Megan was recently working on releasing singles, scheduling photoshoots, and submitting her music to various showcase opportunities, like NPR’s Tiny Desk contest; Sherell had gone back to school online for a Masters Certificate in Music Business and Technology at the Berklee College of Music and also recording her own album.

They have different strengths. Sherell is a more powerful performer, while Megan records and writes more frequently. Megan is frantic in her music, scrappier, passionate in a more urgent sense; Sherell, in her early 30’s, feels calmer about the process, more patient in allowing her craft to improve and gain recognition over time instead of all at once. Neither will ever get mad at the other for pursuing music, even if it takes precedent during free evenings or weekends that would have otherwise been date nights or time together at home. “Sometimes partners just don’t understand each others’ passions or drives, and that’s something that’s really nice in our relationship,” Sherell said. “That when we’re working on music, it’s not that we’re ignoring each other. We both understand that we each need this for ourselves, too.”

A photo from one of Megan’s recent music promotions

They also hope to have kids someday. “It’ll be a few years, because we want them to have what we had growing up, which is a stable home; to be able to give them the world, travel, go to college debt free.” They’d like to have multiple children, and to adopt or foster. “Obviously, adoption means a lot to me personally,” Sherell said, “And I also have zero desire to ever become pregnant.”

Emily, Sherell’s best friend and the officiant at the wedding, told me of Megan and Sherell, “They’re both fierce and soft, and they allow each other to exist in both of those realities at the same time. I’ve seen some relationships where you have one person that is the defender, and the other person who carries the emotional baggage, where each person sort of has a role in the relationship. But that’s not the case with them. They have complete and total equality and validation in every role you’d typically see in a couple. They’re not assigned to one or the other; they just both allow each other to have space in each. They’re incredibly powerful people.”

Sherell and Megan with Emily, their friend and wedding officiant

Megan and Sherell wanted their wedding to gather all the communities they knew would love one another, if only they could meet. “We had this big feeling as Christians to have our marriage and wedding be a blessing and create a home for other people within our relationship,” Sherell said. They started a few nights before by renting a beautiful treehouse home, built into a trio of massive trees on the side of a hill next to a vineyard in Central California, to host all of their wedding party and make sure they could gather and meet before the wedding day.

Megan and Sherell with their friends and family the night before their wedding

After their wedding ceremony, Megan, Sherell, their friends, and I walked to the shore for portraits, balancing on the hand rails and damp rocks that would soon be swallowed by the rising tide. We walked to a cliffside bluff that was the original location for the ceremony, paved in red dirt and shaded by low-hanging trees overlooking a vivid turquoise-blue ocean.

Portraits from Megan and Sherell’s wedding

Their reception was held at the same place where Sherell first realized she was in love with Megan, a restaurant in Cayucos named Lunada Garden Bistro. Three of their friends, also local musicians, (Cassie Nicholls, Regina Basin, and Douglas Romayne with Donna Wolfe) performed during dinner. “I think it’s really appropriate that we’re doing music here today because music is how I met these two women,” Douglas said, Donna next to him. “It was at two different times, but that was our introduction. And, it was how I met this woman standing with me.”

Performances during Sherell and Megan’s wedding reception

After the last performance, Megan stood up and walked over to the microphone. “I didn't prepare a speech, but looking out at all you, every single face here. You’re our community. We handpicked each one of you to be here, and none of you are here out of obligation. Each one of you holds us up with your friendship and your support. It's why we thrive. So thank you for being here. Thank you for celebrating our love. Thank you for being a part of our journey.”

She smiled and looked at Sherell. “I have a surprise for you.”

A few days earlier, Megan claimed she wouldn’t sing at the wedding. “It’s our wedding, not a gig,” she’d said. Sherell objected. “It’s what brought us together.” Megan held firm. “I don’t want to play.”

Whether she changed her mind or she always planned to sing, I don’t know. Either way, Sherell’s mouth dropped open in surprise. The opening arpeggios to Regina Spektor’s Us began to play, and Megan began to sing:

They made a statue of us

And then put it on a mountain top

Now tourists come and stare at us

Blow bubbles with their gum

Take photographs of fun, have funThey'll name a city after us

And later say it's all our fault

Then they'll give us a talking to

Then they'll give us a talking to

'Cause they've got years of experience

Megan singing to Sherell at their wedding reception

Sherell welled with emotion. She stood up and walked over to Megan. She put her arm around her waist, and sang the song’s chorus in harmony, tears dropping from her crinkled eyes.

And it's contagious

And it's contagious

And it's contagious

And it's contagious