My story of growing up, discovering photography, and deciding to quit my engineering job to start this project.

Vincent Po // Edmond, Oklahoma // December 15th, 2019

I got my first camera the summer after freshman year of college. Princeton’s competitive environment had taken its toll on me, and so I hoped to find a hobby that would make me happy for the sake of happiness. I ended up trying photography, and in the four years since have taken over 300,000 photos of more than 10,000 people, many of whom are now dear friends.

Today, I work as a full-time wedding photographer, documenting stories of life and love across the country, but the transition from hobbyist to professional was a path far from inevitable, and further from planned.

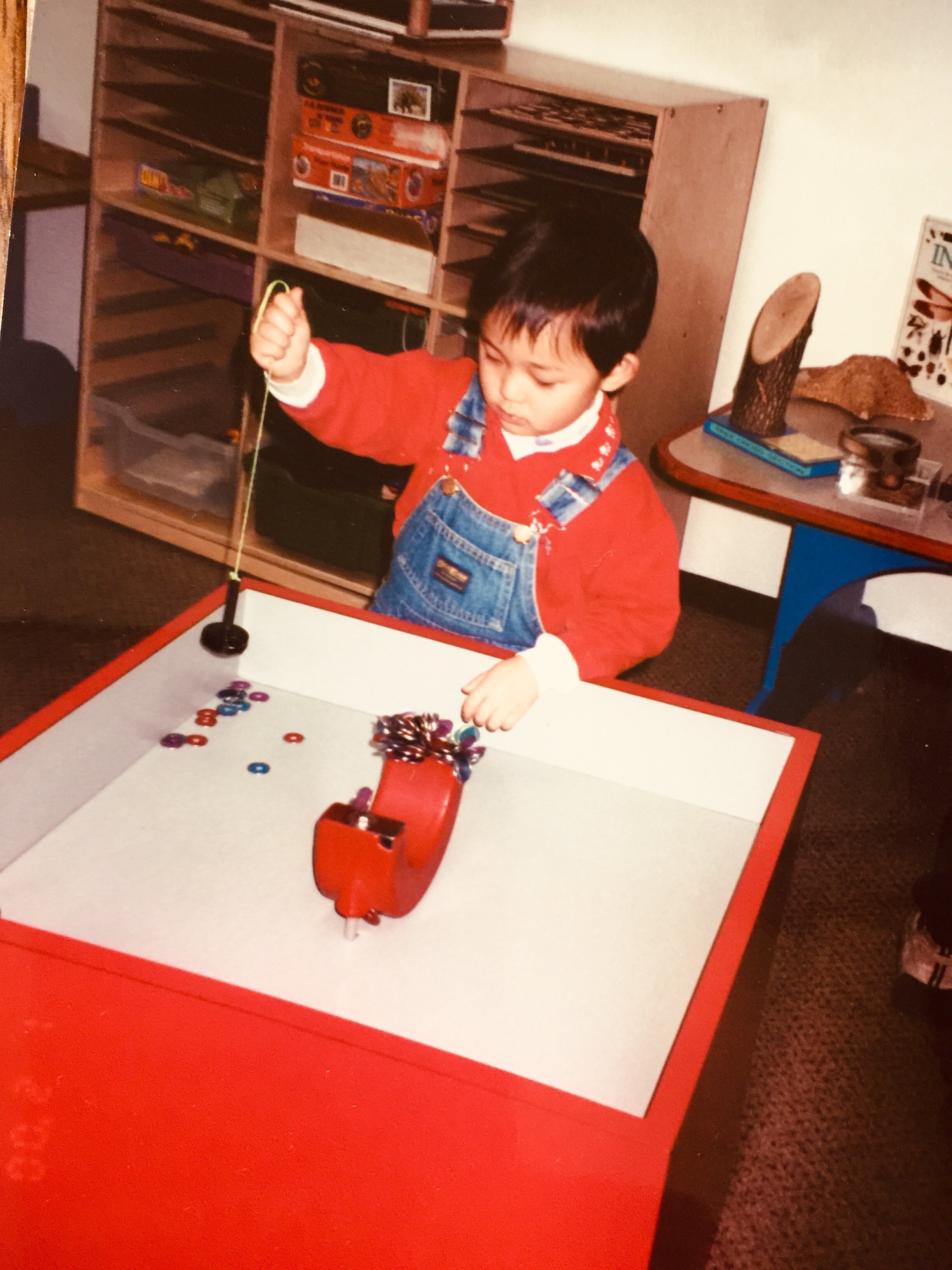

My childhood brimmed with a curiosity turned love for science and mathematics. My father is a doctor and my mother a former computer scientist, and though they often disagreed on how to raise me, both felt it important to expose me early to the wonders of the natural world. Among my earliest memories are road trips my parents and I took to science museums across the country, where we wandered through exhibition halls about plate tectonics and magnetism and plant biology and outer space.

Photos of me with my parents at science museums

We’d often spend days at these museums, and even though my parents could have explained things themselves, they rarely did, allowing me the time to read and play and learn over and over again until I was satisfied with my understanding.

They allowed my thinking to progress organically, rather than be rushed to an answer, and they instilled curiosity for curiosity’s sake. If their goal was to set me on a path to study math or science, they never said so, and never conditioned their support on my career choice. But all those experiences outside of school reinforced those within, as the classes I took made me even surer that it was for me. I was hooked, and by the time I left home for college, I was set on becoming an engineer.

Me with my mom and dad at high school graduation

As for many people, college was a bit of a culture shock.

Princeton has many traditions, one of which is called the “step sing” where the entire class gathers to sing both classic and pop songs on the steps of the most iconic arch on campus

I grew up in a quiet suburb of Oklahoma City, and as the only child to immigrant parents, I carried their expectations and love in equal measure. I was pushed, but rarely pressured, to do well in school, and the same was true for other activities too, like music or scouting. I got to think for myself and have the support and resources to work hard in areas I chose, and so, at least for my community’s standards, I excelled.

I played violin and viola, and became an eagle scout in 8th grade. Both were things I chose to do and enjoy, though my parents did admittedly nudge me towards the beginning of each

This lack of pressure stood in a sharp contrast to my peers at Princeton, many of whom held competition as their motivation and pressure as their fuel, something I found unenviable until I realized it was also, partly, why they were world-class scholars, dancers, singers, actors, and athletes, when I was none of those things.

I felt out of place in almost every interaction that first year. I wish I could say the feelings I held towards my talented peers rooted purely in admiration and curiosity, but the truth was that I was deeply jealous and rather fearful about my own inadequacies. I was rejected by the orchestra on campus before my first week of classes had even finished, which was devastating because most of my social life growing up had come from the musical community. Playing in orchestras and chamber groups meant a huge deal to me, and most of my closest friends were orchestral peers, not academic ones.

Photos from my high school orchestra days. I’m on the far left in both pictures

I remember walking around campus in the following weeks feeling twinges of longing whenever I passed someone walking to or from rehearsal. How close we were to being friends, I thought, if only I were more talented. It’s a silly thing to think about now, since I could’ve experienced so much worse that first year. But I really did long for those friendships.

Who were all these incredible people, and what were their stories?

Throughout that first year, the boiling excitement I had towards college tapered to a simmer of incomplete and confused feelings. But, as often happens when we reunite with the people who matter most to us, and love us regardless of our achievements (or lack thereof) I felt better as soon as I got home for the summer. Instead of doing anything academic or career related, I spent time with my parents, and the curiosity they cultivated for so long during my childhood came blooming back. In an environment where I didn’t have to compare myself to anyone else, I had permission to try new things that might make me happy for the sake of happiness.

First, my mom taught me how to properly cook. In the years before I left for college, my family had a tradition where, on Thanksgiving and Christmas, I would cook for all of us. The tradition was born out of one particularly sad year where we all ate dumplings (frozen, not even handmade) for Thanksgiving because we didn’t have guests and no one wanted to cook. I volunteered to cook at the next holiday and my parents happily agreed. That Christmas, we borrowed a bunch of cookbooks from the library and flagged anything that looked tasty and not too difficult to make. Like how they let me play and learn on my own as a kid in those science museums, my parents let me learn how to cook at my own pace, too. (Maybe, though, they just enjoyed the break.) It became a tradition in our family that continues to this day anytime I’m home.

I always made an eclectic mix of dishes, with no sense of timing or order, and certainly no guarantee for how things would taste. One year I made a ribeye steak at the start of the day (which I completely overcooked, setting off the fire alarm in the process) and omelets for dinner, with dessert inserted somewhere in the middle and appetizers throughout the day.

Because I only cooked on these holidays during high school, I didn’t retain any techniques, so that summer my mom properly passed down her own knowledge of things like knife skills and flavor combinations. It was a tasty hobby, and a new way to do something nice for my parents each night at dinner.

As a Taiwanese-American, I felt it fitting to learn dishes from my mom that she’d grown up eating

Second, my dad taught me a bit of guitar, though “taught” is probably too generous; he busted out an old guitar that had been collecting dust in our attic, showed me a few chords and strums, and sent me on my way. (Noticing a pattern, yet?) After a few painful weeks, I managed to play some decent chords and even learned some finger picking techniques. A lot of the concepts came naturally from playing violin my whole life, and by the end of the summer I even filmed myself playing a cover of I Will Follow You Into The Dark by Death Cab for Cutie, which, if you know the song, is just the right difficulty level to be easy while sounding impressive. You won’t find that video anywhere now, but here’s a screenshot of what it looked like.

This looks far more impressive than it actually sounded

And third, I taught myself photography. It was something that I’d wanted to try for a while, but in the same way that everyone wants to travel more: romantic as an idea, but realistically out of reach without both lots of time and money. I’d spent the year, however, admiring two of my classmates’ work from afar (Kathleen Ma and Eric Hayes), and when I looked into how much getting a camera might actually cost I was surprised to see that I could get an acceptable DSLR with my savings from many years of collecting red envelopes at Chinese New Year.

My new camera arrived in the first few days of summer, and I took pictures of everything I could, no matter how simple or cliché. I was totally fascinated with everything about photography, learning lighting and editing and composition for the very first time through YouTube videos and by annoying my friends to pose for me.

Photos I took the first day I got my camera. It doesn’t get much more cliché than bikes and windows

On a trip at the end of the summer to visit my mom’s family in San Fransisco, I took a full day to wander around the city on my own and take pictures. Having a camera gave me reason to pay closer attention to my surroundings. I walked more slowly, and looked and listened more closely to all the people and animals and buildings and ocean sounds around me.

San Fransisco is beautifully relaxing to walk around, and like all cities it’s easy to be just another anonymous person among the crowds

I also took pictures of people. My very first “photoshoot” was with some friends from college, and it was hilariously awkward. But past the awkwardness was a deep joy, one for which I didn’t yet know the root cause but yearned to experience again. By the end of summer, I was actually excited to return to college.

As awkward as these photos were, they were still so much fun to take

Back on campus, cooking and guitar were both out of reach (there wasn’t a kitchen in my dorm, and the guitar, I decided, wasn’t worth the extra cost to fly with) so I signed up to take photos for the school newspaper as a way to keep up with photography. I bounced from event to event, whether that was a football game or a guest lecture, and though I was only being paid in “experience” and “exposure”, as a new photographer that was actually quite valuable.

Photographing for the school paper put me in environments I otherwise would’ve likely never gone to. The above picture is of a lecture given by the violinist Itzhak Perlman

(One time, I even got to travel to the White House for a press event, which was an awesome experience but a story for another day.)

Security at the White House is surprisingly chill once you get past the main gates. I expected to be chaperoned everywhere, but you’re mostly free to wander around the western side outside the press gallery

I also continued doing photoshoots with friends. Fall in the northeast is absolutely gorgeous, and the perfect time for pictures. I’m still thankful for the many wonderful people who agreed to work with me even when I was clearly still learning.

Having a camera and sort-of knowing how to use it made for a fun way to meet new friends

As I kept photographing people and events around campus, I discovered just from where that deep joy from the first photoshoot came. Everyone, at some point, needs a nice photo of themselves. Whether for work or for fun, it’s how we present ourselves to others in an increasingly digital world. The promise of a good photo is something few people can ignore, and with my camera, I suddenly had the reason and ability that I’d so longed for my first year to connect with the talented people who surrounded me.

Instagram may try to teach us that photoshoots are glamorous, staged affairs, but to me a photoshoot has always been much more akin to getting a meal with someone. Just as a meal serves to not only nourish but also create time and space where people can gather, so a photoshoot is not just a chance to take nice photos but also a way to create an environment for people to learn about each other. Photoshoots often begin quite awkwardly—very few people are totally comfortable being in front of a camera—and so they’re wonderful opportunities to learn how to make people feel more at ease around you, something that’s core to good conversation.

I was soon doing multiple photoshoots a week, hooked on this new way of meeting people. And meet people I did: I estimate that I took over 200,000 photos of around 5,000 of my peers during college, and developed my own style for not only photographing people but having conversations with them, too.

Two of the more unique photoshoots I did on campus, and some behind-the-scenes photos too

One set of photos I shot stood out among the rest. The Other Side of Me is a photo campaign I helped start to provide an open and encouraging platform for students to engage in thoughtful reflection on the experiences, people, and ideas that have defined or changed who they are and how they think. I took the photos, and had people write and submit their own stories, rather than conduct interviews myself.

What followed was an incredible range of personal stories; self-image, family deaths, identity, poetry, sociopolitical commentaries. For the first time, I realized that my work could be used not just to make people happy, but also to help others tell their stories by giving them the confidence and context to share.

"My dad died unexpectedly 10 days before I started my freshman years. It was only 36 hours from ER to the last call, so between that and packing for school I barely had time to process until I was here. At first, the new environment was the perfect relief from my grief, I was distracted, busy, and surrounded by love and friends.

But something one of my high school teachers told me turned out to be true: the outpouring of support is great, but it can’t last. People have to move on. You can’t stop the world while you grieve.

It didn’t really sink in until the end of first semester, but by intercession I had reached that point where other people had to move on with their lives but I still couldn’t get out of bed. Every day it crosses my mind that I should have taken a semester or year off, and there is an omnipresent feeling of wanting to go home, but also knowing that the home I knew and was used to before college doesn’t exist anymore.

I’m insanely grateful for my friends, for PDP, and for my rowing team, without you as my standin family I wouldn’t have gotten this far—but I still have a long way to go."

"I grew up in a home where I would’ve been criticized for this sort of smile—“Don’t laugh like that. Your eyes disappear, and you’ll get wrinkles.”

I also grew up in a world where classmates wore size 00 jeans, and I was told that Asians were supposed to be slim. So I lost weight, and then more weight, and what people called “naturally slim” revealed itself to me as a nightmare masked in “fitness”. Thanks to friends and family <3, UHS and CPS, I’m consistently moving away from that—but because life is a process, and I am a work in progress, I still face the occasional terror of looking into the mirror and seeing a stranger, or trying to ignore the way my parents’ eyes linger on certain parts of my body when I go home.

It’s like living in a house for 21 years, yet not being able to call it home. I’m making it home again, though. It’s remembering that people go home for Thanksgiving, they’re not thinking about the roof, or the color of the bricks, but everything that’s worth loving inside.

I hope that this raises awareness—that health isn’t something to gamble with, and that being mean to yourself never did anything. Life’s too short to count your almonds!"

"Turkey's been through a lot of political changes for the last ten years. At first, everyone thought these changes weren't big of a deal. Later, they turned out to discriminate people who held onto ideologies that were not in accord with that of the authoritarian government. When I left for college, I still had hope that I would eventually come back to a more welcoming environment, but things turned out to be the other way around. Instead of celebrating the individual, the government sustains a constant state of turmoil and fear to crush him. In response, I've promised myself that I would hold onto the beliefs that constituted me as an individual.

Meanwhile at Princeton, some of my friends ask me what it's like to live in Istanbul or Ankara. Whenever I try my best to explain the situation that I call my family and friends on a regular basis to make sure they are still alive, some of them often think this is not so abnormal given Turkey's location. As much as I would like to argue against this type of reasoning, they aren't interested in seeing a confrontational side of me. As this portion wants to stick to their judgments, I don't want to push their limits any further. But then, another explosion happens in "a more civilized and geographically close" part of the world, and all of a sudden, this group realizes something abnormal has been going on. Again, I try my best to confront them with rationalizing the death of one person over that of the other, and that every single person needs this type support regardless of any factor. But then, they dismiss my arguments on the grounds that there are factors.

Whether this portion ever gets comfortable with it or not, I won't ever give up on coming up with the other side of me because I keep my promises."

Meanwhile, as I spent more time on photography, I also spent more time on engineering, with classes and research picking up, and entrepreneurship, where I helped organize the school’s startup competition.

The robot I helped build for my Junior EE design course. We created a “guard” bot, which would patrol the lab, detect loud noises, shine a light in the direction of the noise, and use a camera to verify an ID card

The team I helped lead, called TigerLaunch, during our Chicago event

Each taught me something unique about the world and my place in it. Photography taught me to question my own beliefs by providing a space to meet people who lived and thought in entirely different ways from me. Engineering taught me that the world is predictable and within your control, as long as you use the right frameworks and techniques. And entrepreneurship taught me that starting something was not only possible but feasible, given the right skills and mentors. For the rest of college, I split my time among these three types of work, and at the end of the four years looked back with a lot of pride in how I had changed as a person and all that I’d accomplished.

Me and my parents at college graduation

After graduation, I found an incredible fellowship called Venture For America, which recruits and trains recent graduates to work at startups in cities with non-traditional but vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystems, like Detroit, New Orleans, Baltimore, and my eventual city, Providence. VFA allowed me to combine my interest in entrepreneurship, technical skills from engineering, and curiosity for people through photography in one place, and surrounded me with others combining their own skills in creative and inspiring ways.

Many future CEO’s in this photo! I’m somewhere in the top left

By August of 2018, I’d started work as an Electrical Engineer at Loft, a product development agency that helps companies design, engineer, and manufacture products. I had the incredible opportunity to work with big clients like Bose and Mattel, as well as smaller startups, building products in the medical, marine, consumer, and industrial industries. I genuinely enjoyed my work, and I learned a lot on the job about engineering and about building real products.

My company’s welcome post for me, a little delayed but better late than never

But half a year in, I began feeling unsure about whether electrical engineering could ever really become my “life’s work.” Part of me wondered if this was just because it was my first job out of school, and that it’s hard to find what your “life’s work” is when you’ve experienced so little of either. But another part of me questioned if the real reason was that, even after all these years of believing I’d become an engineer, I just wasn’t interested in it anymore.

A few of my coworkers and I were once interviewing a prospective intern about his side projects. He talked about all the crazy things he was building, like a battle-bot to fight other battle-bots, or a retro-fitted electric skateboard, and as he shared, I felt a strong sense of confusion mixed with surprise, because I realized that if I’d been asked the same question, I’d have very little to talk about. I didn’t spend my evenings after work tinkering on side-projects or learning new engineering skills, and it wasn’t even because I was avoiding it. I just didn’t have the desire.

I’d graduated from engineering school expecting to continue to feel the same curiosity and excitement towards science and math and engineering as I’d felt up until that point, and, to some small degree, I did feel it in my job. But what I should’ve noticed earlier was how engineering no longer held the same place in my life as it did before. Over the previous few years, I’d spent more and more of my energy on photography and entrepreneurship. That continued when I graduated and went into engineering as I spent my nights and weekends building up a wedding photography business, and finding any opportunity I could to continue photographing people and events.

Engineering taught me to think deeply and logically about problems, but the relationships I made through photography taught me how to think about new problems altogether. They exposed me to ideas and cultures I likely wouldn’t have encountered otherwise, and lent me permission to immerse myself in communities different from my own.

Sometime after realizing that engineering didn’t hold my curiosity anymore, I thought of a photographer named Shantanu Starick, whom I’d heard about a few years prior during an internship.

After many years photographing as a traditional freelance photographer, Shantanu had the idea to see what would happen if he removed the financial transaction from his work, and instead traded his skills not for money but for basic needs in life. What he discovered was that people were not only very willing to make this trade, but that by removing the financial transaction he’d opened up the possibility for deeper friendships. He was, after all, sleeping on the same couches his hosts would use to host their own friends, and eating the same food they’d normally cook for their own family. By removing money from the equation, he’d given others the permission to pay him in their kindness and hospitality, and thus to develop friendships that went far beyond a photoshoot.

When I remembered this story, I noticed that the feeling Shantanu felt was the same that I felt working as a photographer in college. The people I photographed were peers first and “clients” second. They were people I’d meet again in class or in a dining hall, and just as staying in people’s homes gave Shantanu the privilege and permission to become friends with them, so being classmates with the people I photographed gave me the same thing. I found it thought-provoking that I’d discovered this same feeling so early in my life.

Up until this point, photography had never crossed my mind as a full-time career option. I’d always been good at and liked engineering. It’s a field with very defined and stable career paths. A lot of my friends in the entrepreneurship community constantly obsessed over “impact” and “scale,” and how being an engineer achieved both of those. Becoming a photographer, on the other hand, seemed at odds with both of those ideas.

But now I started to question all of this. Was engineering really the best path to one day starting something meaningful? More importantly, even if it was, was it really the best path for me, especially when it was evident that it no longer sparked the same curiosity or passion in me that it used to?

It took months of honest self-reflection to answer this question, time where I wrote down pages and pages of my thoughts and had epiphanies only to realize they didn’t really make sense. But eventually, all paths, from my past experiences to future goals, lead to two core types of work: shaping culture, and encouraging curiosity.

Culture is “the characteristic features of everyday existence (such as diversions or a way of life) shared by people in a place or time,” and is a powerful force within companies and within society. It causes us to open or close ourselves to friends and strangers, and can change us for the better or for the worse.

Culture exists as a way to describe how a community of people behaves. A community, in turn, is formed as the result of 1-1 interactions, which can be as short as a passing smile or as long as a friendship that lasts for years. And 1-1 interactions are fundamentally the result of how two people view and treat each other

To build culture then means, in part, to define and shape how pairs of individuals interact with and treat one another, and to shape how people interact with one another is to shape their sense of curiosity. Curiosity forms the backbone for meaningful interactions, which are the basis for healthy communities and cultures in companies or society at large.

You can see for yourself how this plays out in your own daily interactions. How often do you make small talk at a party where a lack of curiosity causes your mind to drift elsewhere, or sat intensely curious during a lecture, hanging on to a speaker’s every word, or even been on a really wonderful date where curiosity prompted one question after another?

Curiosity in another person, or the lack thereof, might singlehandedly determine the quality of relationships, and thus the quality of cultures. What makes the latter so hard then is that we all have different triggers for our curiosity in another person. Often, it’s a shared interest or background, like following the same niche band or growing up in the same part of the country. Other times, it’s related to goals, like the curiosity a student shows a mentor who might help in their career.

But curiosity can also be expressed for curiosity’s sake. People who are incredible conversationalists know this well. No matter the topic of conversation, they can seemingly talk about it with ease. They ask the right questions, provide their own stories, and contribute to a conversation with grace and charm, because they’re curious for curiosity’s sake. They break out of their own selfish reasons for being curious, and accept that simply learning about something and someone new is itself a valuable thing.

This thinking came to a head as I realized that at the root of all of my most meaningful experiences was this idea of building culture and encouraging curiosity, both in myself and in others. Whether I was leading a team or photographing a friend, what excited me most was shaping how the people around me communicated with each other.

Engineering itself could no longer provide me with this kind of fulfillment in my career, but figuring out how exactly to transition to this new type of work has been far from clear. I wasn’t even certain exactly what kinds of jobs or careers would enable this work on a daily basis.

But what was clear was that anything done to broaden my understanding of people different from myself could only help. As I thought about Shantanu’s talk, and how what I’d experienced during school was what he’d experienced decades into his career, I asked myself whether it was possible to recreate the same feelings of familiarity but on a larger scale. I wondered if it’d be possible to learn about cultures not just from people the same age as me at the same school, but from entirely different walks of life.

And that, at long last, is where weddings come in.

When I photographed my first wedding, about a year after I got my first camera, I learned that a wedding is about so much more than a celebration of love. Weddings are about attending to the full range of human emotion. From love to anxiety to tension to relief, weddings host all those feelings and emotions compressed into one unbelievable day. Weddings also cross every kind of social divide, including politics, geography, ethnicity, socioeconomics, religion, career, or health, and because they gather every influential person from a couple’s life in one place, weddings present one of the best times to understand not just what someone believes, but why they believe it.

The fact that a wedding gathers the most important people in someone’s life, though, also means that actually experiencing all these emotions in someone different from yourself is tricky. Humans are only capable of holding deep relationships with a limited number of people, and chances are that the people who would invite you to their wedding think more similarly to you than differently.

But that assumption isn’t the case for those who work within the wedding industry. Venues, florists, caterers, and photographers regularly attend weddings held by people very different from themselves.

Photographers especially have the unique privilege of even greater access. They’re usually with a couple the entire day, and oftentimes are the only one present during quieter moments, when the couple has a few minutes to breathe and all the emotions of the day come rushing out in a few sighs or gazes into each others’ newly married eyes.

It’s an incredible privilege to play witness to these emotions, but that window into someone’s life does have its limits, as Shantanu felt in his client work. Relationships with clients are almost always very friendly, but something about the financial transaction closes most of them off from more meaningful turns.

But what if you removed the financial aspect? What raw emotion would fill the space left by money?

It’s this question, and the belief that what fills the space left behind is incredibly valuable and necessary to explore, that drove me to begin seriously thinking about becoming a full-time wedding photographer, with my own twist. By offering to photograph weddings for free, something that usually costs families many thousands of dollars, in exchange for a place to sleep and food to eat, I hope to gain candid and natural access to people different from myself across the country, and maybe one day the world.

One of the more unique (and loudest) weddings I’ve photographed. The couple was a part of a brass band, and they all brought their instruments

What I learned and gained from photography clearly shaped my motivations for this project, but so did everything I learned from engineering, which instilled a methodical problem-solving approach to my planning, and entrepreneurship, which engendered the confidence that I could in fact make it work.

While I can’t plan how the new experiences of traveling and meeting couples across the country will affect me, if the past is any indication of the future, then I can’t wait for what crazy combination of ideas awaits me next.

I hope to return to technology someday; my love for science and math is still genuine and still vibrant. But when I do, I want to bring not just the perspective of a past engineer, but that of a person who better understands those outside of the industry, too.

Products, after all, are always built by people, and people come from unique circumstances that shape their beliefs, goals, and fears in different ways. I want my career to be defined not by my job title or the skills I’ve accumulated, but by how much I can actively include people of backgrounds different from my own, and for my work to enable more people from more identities and circumstances to build and use products that do the same.

And so, starting in May 2020, I’ll be photographing weddings across the United States for free in exchange for a place to sleep and food to eat. During this time, I expect to photograph 40-50 couples, visiting dozens of cities in ~35 states and interviewing hundreds of people along the way. I hope to absorb the reasons people come to hold the beliefs, goals, and fears that they do, and peel back the layers of family, friendship, and community to discover how each relates back to one’s own identity.

In the end, I hope I can teach myself more about the lives of people different from me in order to become better at shaping culture in the future, and to inspire others to become more curious about the people around them so that they might be better as well.