A foster dog adoption brings together two single parents with dreams of building a healthcare company and their own woodworking business.

Nedda + Jon // Tybee Island, Georgia

After spending the past decade chasing money and staying in a marriage he knew long ago wasn’t healthy, Jon was tired of living for any reason other than happiness. Recently divorced from his ex-wife, and with his three sons (Tristan, Tyson, and Tanner) in tow, he searched for someone who might offer that missing measure of joy.

Jon with his three sons. From left to right: Tristan, Tanner, Tyson

Divorced and a single parent herself (to a daughter, Ari) Nedda doubted that the love she dreamed of in her younger years—a selfless, magnificent, intense love that would whisk her away like the cool breeze of a crisp spring day—really existed. At her age, she told me, the dating world was like a craft show filled with all of the rejects that nobody else wanted, each trying to make themselves into something they were not.

Nedda with her daughter, Ari

In this gap between Jon’s longing and Nedda’s doubt filled an energetic bully-mix named Cocoa. Nedda and her daughter regularly volunteered for their local animal shelter, and in July of 2019 they took in a pair of puppies whose mother had been hit by a car. They named the two siblings Zuri and Cocoa, Zuri for her white coat and attention-craving diva nature—“Zuri in many languages means some variation of either white, charming, or princess,” Nedda told me—and Cocoa for her white and brown fur that drew an easy comparison to the color of hot cocoa, and her affectionate personality to its sweetness.

Zuri (left) and Cocoa (right) when they were puppies

For two months, Nedda and Ari bottle fed, potty trained, and fell in love with the puppies. When the dogs were healthy enough to be adopted by other families, Nedda and Ari briefly considered keeping them before deciding they needed to leave room for more foster dogs in the future. Through Facebook, they looked for new owners.

Cocoa (left) and Zuri (right) when they were puppies

Jon came across one of Nedda’s posts; his own dog had recently passed away from cancer, and he was looking for a new puppy for him and his sons. He agreed to adopt Cocoa, and Nedda gave him the address of the shelter where they’d meet to sign the paperwork.

Nedda, with Cocoa, on her way to meet Jon at the shelter

As she sat in the shelter’s lobby on the day of the adoption, holding Cocoa and trying not to cry, Jon walked in. “When our eyes met, I swear to you, it gave me chills,” Nedda told me, "but I kept things professional." The two talked briefly about Cocoa before Nedda handed her over to Jon and said goodbye. When Nedda got home, she told Ari, "Cocoa’s new dad is... well, kinda amazing. And hot." They laughed, and went out to dinner to celebrate Cocoa having found a home. (Zuri was also adopted by another family a few days later.)

Jon with Cocoa a few days after he adopted her

Cocoa left Nedda’s home, but Jon stayed on her mind. Every day, when Jon would send her updates about the puppy over Facebook, Nedda would flirt in response; and every day, Jon would keep their conversation professional, steering the conversation back to Cocoa each time Nedda lobbed a playful message his way. Then, one day, when Nedda posted a meme wishing that the neighborhood would hand out tacos and margaritas instead of candy that year for halloween, Jon finally took the bait, and messaged, "Would you settle for tacos with me instead?" Nedda dropped her phone out of excitement.

They met for a late dinner—each had a full day of work and errands before—that same night, September 25th, 2019, at a local sports bar, where other patrons rowdily cheered and booed as they watched the games playing on televisions around the room. Jon arrived first, and saved a pair of seats for him and Nedda towards the end of the bar.

That evening, Jon talked, and talked, and talked some more, sharing openly about the details of his life, and though Nedda didn’t speak much in response, she giggled the entire time. She didn’t mind that Jon spoke so much; her impression of him was of an honest man with a huge heart, who loved the people in his life wholly and loyally. Jon, in turn, remembers his impression being around Nedda as “feeling so comfortable that I was able to talk about everything, even the first time meeting her. When she walked in with that dress, I knew it was over.”

As they left the restaurant, Jon stopped in front of Nedda’s car, a massive lifted gunmetal gray F-150 Platinum. “You drive this big-ass truck??” he asked, amazed, and a little more in love. Now, Jon was the one giggling, as he gave Nedda a goodnight kiss and asked if they could have dinner again the next night.

"Since that first date, we haven’t spent even a single day apart," Jon told me. When their kids met, they quickly developed a bond as strong as real siblings, fighting with one another while also being fiercely protective. "We call our love story the best ‘foster fail’ of all time," Nedda told me with a wide grin, "because not only did Ari and I end up keeping Cocoa, but we also ended up with a grown man and three great boys, too."

Jon and Nedda with Cocoa

When I arrived at Nedda and Jon's home, a two-story property in a cul-de-sac of a newly developed neighborhood in Southwestern Georgia, I immediately felt the bond between their kids that Nedda and Jon had described to me on our calls. Jon's sons—Tristan, Tyson, and Tanner—were 12, ten, and five years old, while Nedda's daughter, Ari, was also 12. Each held a different role among the siblings, Ari acting as the elder, wiser, older sister despite being younger than Tristan, who himself was growing into his own brooding version of teenage boyhood; Tyson a bundle of energy with a modest case of middle-child-syndrome; and Tanner, the youngest, giggly and just starting to grow comfortable with testing the boundaries of his father's and Nedda's authority.

Nedda and Jon with their kids

As is often the case before a DIY wedding, boxes of decorations and partially-filled bags of wedding favors filled nearly every corner of the home. Among their preparations was the large reddish-brown stained pergola in the middle of their garage-turned-workshop. (Jon had, impressively, designed and built it himself.)

Jon and Nedda’s garage, with the wedding pergola in front of Jon on the left side

As I helped Nedda and Jon unload groceries after a run to Sam's Club to buy food and alcohol for the wedding, Nedda smirked, thinking about the old truck she had when she'd first met Jon. “The sad thing is I traded in that truck for a mom-SUV," she said. "Once, Jon and I were unloading groceries like we are now, and I just thought of how I never imagined I'd be living this sort of suburban life."

Suburban, she stressed though, did not mean boring. "There’s never a dull moment.” Jon shook his head in agreement. “Never,” he asserted, giving Nedda a quick kiss before going inside to check on the boys, who had begun squealing at each other, likely to Ari's resigned chagrin.

Jon cleaning out the car and garage after an errand run

Nedda and Jon both work, a lot, Nedda as a rural care nurse and Jon as a manager at a paper mill in Alabama. Nedda described her work as fulfilling, but her travel schedule gave even me, someone who drives around the country for this project, wide eyes. "Right now, I’m on the road about 500 miles a day,” she said.

Towards the beginning of the COVID pandemic, Nedda worked for one of the nearby hospitals as a Director for Regional Operations, strategizing and coordinating the logistics of opening new clinics around the state and expanding COVID testing capabilities to underserved areas. In May, she submitted a proposal for a pilot program that would send staff to rural communities in order to screen children for COVID a few days before they arrived at the hospital for surgeries.

The idea was cultivated from a desire to improve Georgia's under-resourced healthcare system. “A lot of my past experience has been in rural care, so I know where we're lacking in those areas," she told me. "There are a few hubs”—Atlanta, Augusta, Columbus, Macon, and Savannah—“that have good access to care, but almost everywhere else doesn’t.” When hospitals implemented policies requiring children to test negative for COVID before coming in for surgeries, parents had to suddenly make two trips to the hospital with their child: one trip to test for COVID, and a second trip for the actual operation. Nedda realized how inaccessible that would be for parents who already struggled to make it to the surgery, whether because they had to take off work or find money for transportation, let alone come in a few days earlier for a COVID test.

When her proposal wasn’t accepted by her employer, Nedda decided to quit her job and start her own company. Leveraging her prior network, she quickly signed contracts with hospitals in Georgia and began driving around the state to conduct the COVID tests herself, saving the extra trip for parents and helping hospitals reduce costly surgery cancellations.

Nedda showed me her planning process one evening at home, spreading a large laminated map of Georgia on her kitchen countertop and pulling up a herculean spreadsheet on her computer. “This is my life,” she said. “Each week, I get a list of patients from the hospitals along with their surgery date and when they need to be tested by. Then, I mark up their locations.” She took a dry-erase marker and pointed to a group of x’s she’d made on the map. “I have to figure out how to cluster them so it’s possible to drive between all of them in a workday, and within a certain time window before the surgery."

Nedda’s laminated route-planning map

I asked if there were any program she’d been able to use to help automate the process; it sounded similar, in theory, to the various "traveling salesmen" problems I’d encountered in programming classes back in college. “I’ve tried everything,” she replied with a resigned sigh, “but none of them do quite what I need them to do.”

For now, though, she's stuck with this more manual ritual, which, Nedda said, she didn't necessarily mind. "I often get tunnel vision when I find something I really care about," she told me; the company was clearly a good idea, and it served a huge need for many people. The only problem, recently, had been that it was growing too fast. Jon told me, “In the beginning, I kept saying to Nedda, ‘This son of a bitch is gonna blow up faster than you can catch it!’ ”

I asked Nedda what kinds of people she met during her travels. “All kinds,” she replied. "Everyone gets sick. I met a woman once who was using a shoelace as her doorknob to keep the door shut, whose trailer was basically caving in on itself. I was sitting on the floor of that trailer, hanging out with the kids, starting to color in one of these coloring books and just trying to gain some trust. And next thing I know, these kids' aunt, grandma, and all these other strong, beautiful women are like, 'Can we pray over you?' And it was this moment of such humanity. I loved that."

Nedda on the road in her PPE

As clearly as I could hear the exhaustion in Nedda's voice, I also heard joy; her hands and face animated vibrantly as she spoke about her work, a clear display of the pride she took in her ability to better others’ lives. “I wanted to be a doctor since I was a kid,” she told me when I asked about her start in healthcare. “For as long as I can remember, my dream was to take care of people.”

Nedda grew up in Orlando in what she described as a “very, very, very humble upbringing." "It wasn’t the best part of town where I grew up,” she said, “and we never had a house. It was always apartments." At times, her family wouldn't have the money to run the air conditioner to use through the brutal Florida summers.

Nedda in childhood

Nedda’s father was a recent immigrant from Iran—“He left to pursue an education, but in a lot of ways, he was running from things as well… he has always had a very lone-wolf mentality,” she told me—and met her mother while working in a kitchen. They had Nedda soon after. “There was definitely a lot of cultural weirdness at home,” she told me. “My mom was very American, grew up in Pennsylvania, and while my dad didn’t make us wear head coverings, he still had very traditional views of family. They clashed all the time.”

“Physically, I wasn’t allowed to go to parties in high school if there would be boys there,” Nedda continued, “and my mom had me convinced that my dad was going to kick me, my brother, and her out of the house because I was dating someone during high school.” Nedda’s cultural influences were ultimately driven less by her home life and more by the community around her in Orlando. “My dad tried to teach us Farsi here and there, but he wasn't around much, so it wasn't very successful."

She attended a few Persian New Years celebrations as a child, but has more memories from the time she spent with friendly and generous Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Dominican families who wrapped her in Orlando's Hispanic culture. She shared a few memories that stood out. “I went to Catholic church almost every Sunday for a period of time, which was about as far from my Presbyterian/Muslim roots as I could possibly wander; I learned to salsa dance; I watched my friends get yelled at by their moms in Spanish, shaking their chancletas (flip-flops) at them like they might smack them.”

She continued. “I knew I was officially part of the family when I was included in the group of kids getting chastised in Spanish and running from chancleta-weilding moms. Those same mamas, though, also taught me to cook, made sure I had special holiday memories, and were there for me in ways my mom never was.”

Nedda in childhood

When she was at home, Nedda focused on school. “My friends were the hyper-smart and hyper-motivated kids who didn't fit in with everyone else at our school located in the literal ghetto,” she told me, and described doing well as a given. “It wasn’t even necessarily cultural. My parents were basically, like, there's no reason for you not to get A's, so you will get A’s.”

Along with her parents’ expectations, Nedda herself also recognized the value of a good education. “My dad dropped out of college when he was already mostly done with engineering school, and then my mom never even attempted to go to college,” she told me. “So I was kind of looking around at our situation and thinking, ‘This doesn't seem like it’s working.’”

When she enrolled in university, Nedda had enough Advanced Placement credits to start as a Junior. “I knew I wasn't gonna have any help from family coming out of high school,” she said, “so I just busted my butt every single chance I got.” Nedda originally studied to become a doctor, but for private reasons—“family situations eroded,” she said, simply—she switched to learning about the business side of healthcare, specifically pharmaceuticals and drug development. She accepted a job offer as an account manager for a pharmaceutical company right out of school, and has remained in the healthcare industry ever since.

Throughout her career, Nedda has felt most fulfilled when she’s been physically and emotionally near the people whom she serves. “I know it sounds really dark, but the happiest years of my career were when I was working in hospice,” she said, somewhat longingly. “It taught me so much about life, and it’s also why I’m not afraid of dying. Like, I don’t want to die anytime soon, but if I do, that’s ok; I’m very at terms with our existence because of that job.”

Similarly, she’s felt least fulfilled in corporate positions, where her connection to actual patients was polluted by layers of bureaucracy and financial ledgers. “I once took this really high-level Director job, where the paycheck was super awesome,” she said, “and that made little past-Nedda, with no AC at home, really happy. But it felt like such a money-making venture, and I was so far removed from taking care of people that I was miserable.”

Although Jon travels far less for work than Nedda does, his job is arguably more difficult when you consider its hours. "I'm at a paper mill," he told me, "where we make the actual paper for things like beer cartons and other containers." The factory he works at runs 24/7, 365 days a year, and he and the other workers rotate through a Southern Swing Shift: seven days on one 8-hour shift (8am-4pm), two days off, then seven days on the previous shift (12am-8am), two more days off, then seven more days on the previous shift (4pm-12am), and repeat.

Jon has been on that schedule for 15 years now, and the main problem, he said, wasn't even the shifting schedule, but the fact that it shifted backwards, opposite to how his body would naturally adjust. (Jon recently developed narcolepsy—a chronic sleep disorder "characterized by overwhelming daytime drowsiness and sudden attacks of sleep"—as a result of his work schedule.)

Despite the schedule, Jon has always worked hard; in his early 20’s, he’d often put in 12 to 16 hour days. Looking back, he readily admits that he was chasing money, and that his motivations were perhaps an overcorrection of survival instincts developed during childhood. "I watched my mother struggle to survive on almost nothing, even with child support," he told me. "So for me, happiness came out of watching people be sad because they never had money."

Jon with his mother

Jon grew up in Smiths Station, Alabama, a town of about 20,000 just across the river from Columbus, Georgia. His parents split when he was 10, and Jon claims to have never really had “goals” growing up, electing instead to make decisions opportunistically based on his natural talents. "My shop teacher loved me, and I was really good at welding, so I just did that," he said matter-of-factly about his choice to go to trade school. The paper mill he still works at today hired him out of college, and he was married soon after to his now ex-wife. When I asked about those years of his life, Jon described them as loops through a perpetual state of chaos. “Life is so much calmer now with her,” he mused, looking fondly towards a smiling Nedda.

Jon with his sons before he met Nedda

Jon possesses a personality that leaves little room for doubt. As a friend, his energy is cozy, and his honey-thick southern accent envelopes you in as much warmth as his bear-hugs do. ("When he notices I'm down, he just wraps me in a big hug and makes everything easier for just a second," Nedda told me). As a father, Jon has the southern voice of God, raining warnings onto his sons when their actions or words cross beyond a tolerable boundary of sin.

Jon with his three sons

His personality fills any room he occupies, but where others with his energy may become overbearing or dominating, Jon is highly perceptive and accommodating, reacting quickly to how others feel and adjusting his own energy accordingly. "I'm always trying to make everyone laugh," he told me, "and I can read a room; look someone in the eyes and tell how they're feeling." He creates merriment from any situation he's in.

Publicly, his only goal at this point in life is finding happiness. "I could be a Walmart greeter for all I cared,” he told me. “As long as it made me happy, I don’t care." But privately, and only when pushed, he expresses more nuance. Nedda, sitting next to him one day, talked about Jon in observations he seemed reluctant but ultimately willing to agree with.

"I think sometimes he doesn't want to talk about the ideas and dreams he has," she began, "Because if they don't work out the way he's imagining, then he's gonna be disappointed." Nedda became buoyant talking about his talents, and I sensed that she wanted to shine light on qualities Jon rarely took credit for. "He's such a good teacher. He takes the time to figure out where you're at, and then to bring you where you need to go. He's probably also one of the coolest woodworkers I've ever met because he can dream up an entire plan for something and just do it."

Jon and Nedda on their wedding day

Jon clarified Nedda’s compliment with his own words: redneck engineering. "I choose to learn things the stupid way,” he said, as Nedda shot him a look, clearly thinking Jon was underselling himself again. "That's the truth," he asserted before Nedda had time to comment, recalling a time when Nedda had spent some time with his father and understood, afterwards, the origins of his practical mind. "No shit, the man had to move a little mobile carport. You would've needed 10 people to move it and he moved it by himself," Jon half said, half chortled in entertained disbelief. Instead of assembling a team of people to pick up the carport, which weighed nearly 1000 pounds, Jon’s father had lifted an edge of the port, placed a long wooden board beneath it, and used a tractor to scoop the entire structure off the ground. He then drove a few hundred meters over to where he wanted it to go, and set it back down with a gleeful thud.

Jon’s father cleverly moving a carport with wooden boards and a tractor

"Work smarter, not harder," Jon concluded.

Nedda, laughing through the story, leaned over to Jon and wrapped her arms around him. "Get him into a genuine conversation, where he's not putting on any sort of show or trying to entertain people, and he's one of the smartest people you've met in your life. And I've met a lot of 'book smart' people."

I saw for myself what Nedda described one afternoon as Jon showed me some of his past projects in Sketch Up, a 3D modeling program used by both hobbyists and professionals. Jon had used the program to quickly design an impressively comfy swinging couch in their backyard. Oftentimes, he didn't even need the program before he had already finished outlining the plans in his mind, after which he bought the raw materials and, with swift precision, made marks, cuts, and full assemblies in just a few hours.

Jon showing me the plans for the hanging couch he built for the backyard, and the finished product outside

(The first time we talked to discuss participating in this project, Jon and Nedda answered while in their garage, in the middle of building a beautiful crate for their dogs)

A double dog crate Jon built for their dogs

Before Nedda met Jon and became a “bonus-mom” to his three sons, she was a single mom raising her daughter, Ari, whose father passed away when she was four, and who has been Nedda’s one consistent light and sidekick in life ever since.

Nedda first described Ari to me as being “11 years old but going on 30,” a girl who carried herself with a maturity and self-assured discernment between right and wrong more common among adults than middle schoolers, and which she made evident by gently admonishing her step-brothers when their antics grew out of hand. Her attitude, Nedda told me, came from the years the two spent together on their own.

Nedda with Ari

Soon after graduating from college and taking a job in Texas in the pharmaceutical industry, Nedda met her ex-husband. "I had a terminally-ill patient whose birthday was coming up,” Nedda told me, “and he'd always wanted to be in the Marines. So I went to the Marine recruiting booth at the mall to see if I could get some posters and stuff to decorate his room, and when I explained the whole story to the recruiter, he said, ‘I'll do you one better. I'll deliver all this stuff, posters, shirts, to him myself in my dress blues.’ That was Ari’s father."

The two married, but divorced a few years later after they had Ari and he returned from a deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan. "He was not the same person after he came back from those deployments," Nedda told me. “They took a toll both emotionally and physically, and ultimately I made the decision to focus on what was best for Ari’s emotional health and well-being.”

I didn't press for details—these stories are meant to be a couple's own story, not an exposé of their past relationships—but I found the fragments that Nedda did share enlightening in understanding her and Ari’s deep relationship. “Ari’s father passed away when she was four,” Nedda told me, “after we’d already gotten divorced, and it was probably the hardest and weirdest conversation I've ever had in my life; trying to explain death to a four year old.”

"Because of life, I think she's grown up super, super fast. She's a mini adult, and as much as I've kept her shielded from everything as much as I can, she naturally just learned with us being together all the time." Side-by-side, they adventured through life. “Every weekend we were off finding things to do,” Nedda told me, “from small day adventures to the park or zoo, long weekends to the beach, art projects, baking together, or her 10th birthday trip to Key West. She’s always been my adventure buddy.”

I asked Jon as well about his own relationship with his sons. “Before Tyson, my second son, was old enough to do anything on his own, Tristan, my oldest son, never left my side,” he replied. The two shared a unique bond, one that has gotten more complex as Tristan has grown older, and which Jon thinks about in his relationship with his other two sons. “I guess I want to be known as a ‘good dad’, but as a bit of a friend, too. I didn’t always have the best relationship with my own dad or get to spend much time with him, so I’m trying to spend time with my sons, things like bringing them into the shop, going down by the pond near our house and fishing.”

He continued. “But I'm also trying to get them ready for life. Period. The weeks they’re with us, they’ve got to cut the grass, do chores, stuff like that. They need to learn how to take care of themselves…” He paused for a second, and said with a hopeful yet somewhat longing tone, “I just want them to be good people. Because there are so many people who are great at all this other stuff, but just aren’t good people.”

Jon’s sons before and at the wedding

When Nedda and Jon think about their future, they think first about their kids in the present. "Right now, we're just focused on raising the kids," Nedda told me. "This subdivision suburban life is really good for them because they have friends and it's safe." Their overarching values are simple: "We're not raising assholes, and we're teaching them to be responsible alongside wanting to be happy."

As the kids become older, though, and move away, Nedda and Jon hope to find some land and live a quieter, more solitary life. "We have people we love and want around, but not to the point where we can look out the window and see what our neighbors are doing." They chuckled knowingly at each other; their current home's windows were quite close to their neighbors'. “At this very moment, we literally can see our neighbors’ underwear hanging on their weird clothesline from our kitchen window,” Nedda commented, laughing. “Even though they have a perfectly functioning washer and dryer, they just prefer to have their knickers blowing in the breeze, it seems.”

Neither want to return to their childhoods of financial instability, and I couldn't imagine either of them ever becoming complacent with their work. But, Nedda said for both her and Jon, "we're fine taking a couple of steps back to just have something simpler. Because of the way we were raised, we've learned how to be happy with whatever we have."

Nedda and Jon at their wedding

Nedda hopes to continue to grow her business even after COVID testing becomes less of a need. "We can expand the pre-surgical clearance testing to include more things than just COVID," she said. She talked passionately about rural care. "These rural areas need care so badly, because a lot of these people don't even have a primary care provider, and so they have to go through crazy hoops if they need to see a specialist. If you ask them where they go if their baby's sick, they don't really have an answer."

"Telemedicine is great," she said, "but there's only so much a doctor can do without somebody physically being with the patient. So we're thinking of providing the nursing component of that visit, so that the doctor can do telemedicine, but where there's still a medical person with the patient at their house, checking vitals, operating a scope, whatever it may be." When we caught up a few months after the wedding, Nedda had grown her team enough where she no longer needed to go out onto the road herself most days, which gave her a lot more time to spend at home.

Jon, too, cautious as he is to set lofty goals or to pursue dreams that may fail, became animated while talking about his and Nedda’s future home. "I want to start a woodworking business," he said, "with a little nursery for plants on the side and a shop in the back. We’d live above it," he said. By the time I caught up with them again a few months after the wedding, they were already well along in the new business, called Our Roots Studio.

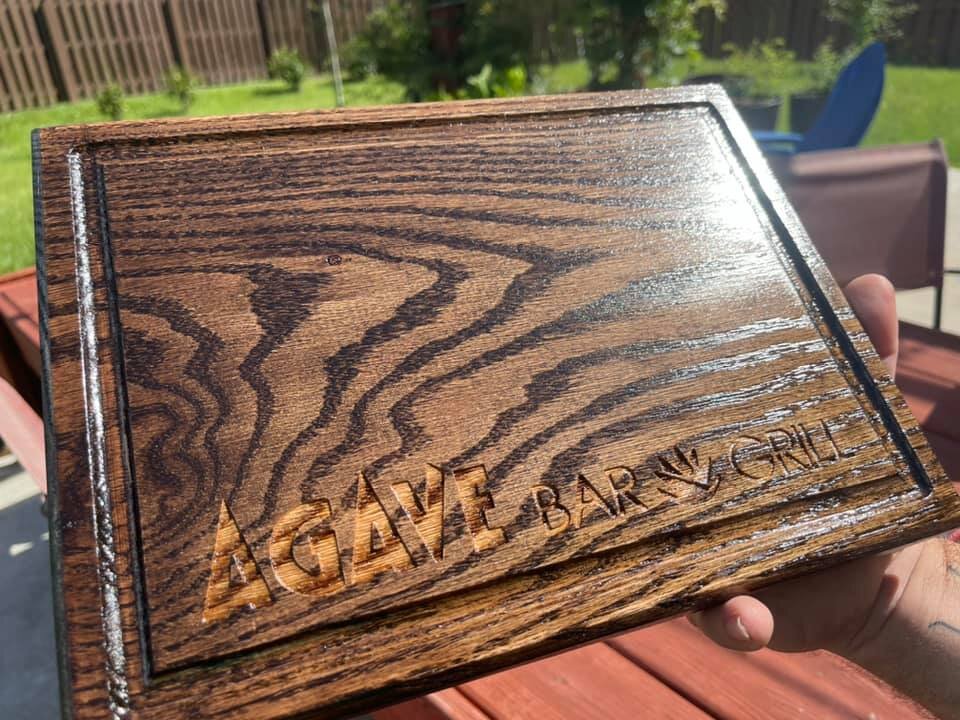

Working as a team, with Nedda managing most of the customer-facing work and Jon doing the cutting and assembling, the two now spend most of their days in their garage workshop, making custom pieces (serving boards and planters are particularly popular) for local families or businesses. They hope to rent some space for a more formal workshop soon, and have dreams of establishing a maker culture in their community, hosting workshops and teaching lessons on woodworking as part of the business.

“We’d love to bring in makers and artists,” Nedda said, “different artisans and crafters into a joint space where people can create and sell things all in one cool spot. There's been a lot of attempts at building the maker culture in this area and all of them seem to fall woefully short each time, people’s mindsets about creating are changing, and it could actually be successful now.”

Nedda continued. “We've both always felt that if you do right by people, genuinely try to treat people well, things have a way of falling into place. We’ve made so many new friends with local businesses, and we can focus on just building those relationships and doing the right thing.”

By the third date with Nedda, Jon was already joking that he needed to start saving for a ring. Just a few weeks after they met, they both brought their kids to meet each other, and it didn’t take long for everyone to become very comfortable with one another. Jon told me that much of their quick connection was built on the independence each already carried in their lives.

“This sounds materialistic, and I don't want it to sound that way,” he began, “but I've never in my life been with that didn't need me. Maybe they needed my paycheck, or the roof over their heads, or food, or something else. But when I started dating her, she already had her own family, her own tools, her own food, her own everything. She didn't need anything from me. But, she still wanted me to be around. And that's a completely different feeling, to go home and know that she doesn't need me there, but that she wants me there. I think it’s so much better.”

Jon had planned to propose in Nashville, Tennessee, in March 2020 while on vacation with Nedda, but when their trip was canceled just days before due to the COVID shutdowns, he made do, instead, with a proposal at home. Nedda had once joked that she’d marry Jon even if he proposed with a twisted bread tie, so one evening at home, after dinner, with all the kids standing nearby watching, Jon looped a bread tie into a ring, and slipped it onto Nedda’s finger. She laughed, and began adjusting the makeshift ring so it’d fit better on her finger, when Jon gave her a kiss on the cheek, got down on his knee, and pulled out the real ring; Ari recorded the proposal on her phone, Tristan watched quietly beside her, Tyson giggled at Nedda’s surprise, and Tanner, who’d been playing on his own a few yards away, uninterested in the whole affair, suddenly saw the ring and ran towards Nedda and Jon for a closer look. (Tyson yanked him back just in time to save the moment.)

(Nedda and Jon both preferred to keep the video of the proposal just between them, but they did take a picture right afterwards that they said I could share here.)

Nedda and Jon after the proposal

Nedda and Jon’s original plan for the wedding included a guest list of over 300 people, but because they were engaged during the pandemic, they quickly pivoted to a much smaller event. Both absolutely loved Savannah, a city known for its beautiful old-style architecture and idyllic qualities as a vacation destination, and just to the east of the city was Tybee Island, a small barrier island popular among beach-goers and sun-seekers. Nedda and Jon wanted to be right by the beach, so they rented a large two-story vacation house within walking-distance of the ocean to accommodate the two dozen or so people attending the wedding and following reception.

Jon and Nedda in front of the house they rented for their wedding on Tybee Island

Nedda’s most important guest was her brother, with whom she's been close since childhood. "We don't talk a lot these days because he still lives in Orlando and has a whole different life than I do at this point," Nedda said, "but at the end of the day, if either one of us is ever in a bad situation, we would both drop everything we have to do to go be there for each other." When she extended an invitation to him, Nedda also offered grace if he had to decline because he didn't feel comfortable traveling. "He asked if I wanted him to be there, and I said yes, and he replied 'That's all you had to say. I'll be there.'"

“My brother and I are the products of two parents who were immensely unhappy with themselves, their lives, and their relationship—and it made for a very unhappy, volatile home,” Nedda told me. “We both just did the best we could with what we had, and were there for each other when we didn’t have much else.” Neither of Nedda’s parents were in attendance; she hasn’t been in contact with her mother in almost 20 years, and while she would be happy to welcome her father in her life, the relationship carries its own decades-long baggage of unhealthily seeking love and approval.

We—myself, Jon, Nedda, the kids, and a few family and friends—made the four hour drive from their home in Southwestern Georgia to the eastern coast of Tybee Island the afternoon before the wedding, arriving to a warmth and humidity that swayed between being tolerable and not. The house Nedda and Jon rented was classically southern, with wooden floors, high ceilings, and old remnants of life from a different time: a writing desk that begged for you to bring parchment and a quill pen to write on, opaque off-white frilly curtains, and a system of connected pipes in the walls that acted as an intercom system and which the kids delighted shouting into.

A room inside the vacation house Jon and Nedda rented

The evening before the wedding, everyone helped to unpack the cars and fill the home, stuffing the fridge with groceries and drinks for the next day. Nedda and Jon spent part of the evening cooking together, browning and seasoning large logs of ground beef and searing bags of shrimp for the homemade taco bar they’d serve at the reception in honor of their first date over tacos. As they cooked, their children and nieces ran up and down the stairs of the four story home (two main floors, a small basement, and a tiny attic), entertained by the simple fun of exploring a new environment. As the sun set, I sat in a small rocking chair on the second floor porch, which wrapped all around the house and overlooked the beach just a few hundred yards away.

View from the house’s second floor porch; straight ahead is the beach, just behind the trees

Nedda and Jon's wedding day began casually the next morning. Jon's sister, Bailey, helped Nedda and Ari with their hair and makeup, while Jon, who wouldn’t need as much time to get ready, cooked a small mountain of bacon and eggs for everyone in the kitchen.

Bailey doing Nedda’s hair

His groomsmen, most of whom had stayed in other hotels in Savannah, arrived late in the morning and quickly rewarded themselves with beers and naps after they finished putting on their suits.

Jon enjoying a football game with his groomsmen

Nedda and Jon’s ceremony was held on the public beach a few hundred yards away early in the afternoon of October 24th, 2020. Nedda and Jon didn’t bother with chairs, and there was no formal aisle; Nedda walked, instead, down the path from the house to the beach with Ari by her side, Jon squinting beneath the bright midday sun to catch a clear view of the two of them.

Their wedding party stood on either side of them, and a small gathering of other friends and family stood in a haphazard cluster in front of them. Jon's father officiated the ceremony.

"You can believe in destiny, or a higher power, and believe that your whole life is planned out, and that this was supposed to happen the whole time. And you can believe in spontaneity, where things just happen, and that two people just find true love where it wasn't destined to be there."

"But I know the real story of how Jon and Nedda got together." He smirked. "I heard Nedda was looking for a dog. And so she looked around at a lot of places but didn't find what she was looking for. And then she picked up a stray. And she loved it, and groomed it, and fed it, and gave it a place to stay..."

"So yeah, I think Jon found a home!"