Living life as Latter-day Saints, and a bout through abuse, divorce, and single motherhood.

Sarah + Paul // Indianapolis, Indiana

In front of the white tent, pitched the previous day in his and Sarah’s backyard, on a surprisingly mild and sunny late-May day, Paul knelt down to speak with the two young boys. “Isak, Jakob,” Paul said quietly, looking up from his notes, a bright, watery sheen already reflecting off his eyes. “Before I can do my vows to Sarah, I first need to talk to…”

Paul reciting his vows to Isak and Jakob

Paul paused for a long moment. His brows furrowed a bit; lips pursed, then relaxed; eyes shut, then slowly opened. His mind darted through a range of emotions as he looked first towards Isak. He paused often. “One of my favorite things about you… is when you sing, and dance. I love your sense of humor, and your curiosity, and your desire to always… control the game in your favor.” The gathering of friends and family chuckled; even I’d noticed, when we played Mancala a few nights before, that Isak had a sneaky penchant for cheating.

Playing Mancala with Isak and Jakob a few days before the wedding

“You’re a great older brother. I know you don’t always feel this way, but I know you love Jakob. I love how protective you are.” Paul took another long pause. I thought of a memory he’d shared with me before, of when he tickled Sarah one night, and Isak ran over and hit him over and over because he thought Paul was hurting Sarah.

Paul’s voice waned quieter after each pause as he tuned out more and more of the world around these boys. He turned to Jakob next.

“You are honest. You always tell the truth. Sometimes, a little too much, like when you couldn’t hold it in anymore, and you told me what your mom got me for Christmas. I love how much you love to play with stuffed animals and dinosaurs. And how much you love to play with your older brother.”

Isak and Jakob under their mother’s dress at home

“You have a great talent for gymnastics. You’re athletic. And you’re fearless. You're growing up so fast, everyday, and I'm so excited that I get to be a part of watching you.”

Jakob playing with water in their backyard

Jakob, ever a kind and patient child, stood, smiling, listening to Paul the entire time. Isak, after Paul had finished talking directly to him, became fidgety. He soon plopped down in front of his mom.

Isak had become tired of standing after a few minutes

“This is taking longer than I thought it would,” Paul smirked, perhaps noticing Isak’s restlessness. “I have a question for both of you boys. Can you stand up?” Isak begrudgingly complied.

An emotional Paul sharing his vows with the two boys

“I want you both to know that I love you both. I learn so much every day from you. I'm not perfect. I will make mistakes. But I promise that I will always do my best to be as good of a parent as I can.”

“I also love your mommy. Very much.” Paul looked towards Sarah, who by now had also wiped away a few tears. “And I want to live the rest of my life with her. But before I can do that, I need permission from the most important men in her life. Do you know who those important men are?” A knowing, mischievous smile crossed the boys’ faces. They pointed at themselves.

“So. Do I have permission to marry your mommy?”

The two boys nodded, eager, I’d wager, both for Paul to marry their mother, but also for the chance to sit back down. They ran back to their chairs.

Sarah told me about the first time she saw Paul, about three years after she’d left her previous neglectful and abusive marriage. “Literally, the first time that I saw him, I laughed to myself, and I thought in my head, wouldn’t it be funny if that turned out to be my future husband?” Paul was attending a church event for singles over 30, and had been sitting in the one spot that Sarah could see from the building’s foyer. “We made brief eye contact. And then he looked away, and I was like, Oh, ok, never-mind. My future husband would never look away.”

Photo from a small shoot we did at the little lake by Sarah and Paul’s house

“I didn’t want to seem creepy,” Paul offered in defense. “Plus, Sarah was 26 at the time, and had thought the event was for younger singles, before realizing, oh, these people are old. And I knew it was for older people, and I also thought, oh, these people are old.” Paul was recently divorced as well; he’d moved to Indiana from his home state of California a few months prior.

“I thought I had made a big mistake,” Sarah said. She’d come with her two young boys, and realized she was now causing a scene. An older gentleman noticed her discomfort, and came up to chat. He came back to Paul a few minutes later. “I told her that you might be interested in meeting up for a date sometime,” he told Paul.

It took a few months to meet up, but when they did, they had a simple dinner, and then spent the rest of the night playing board games. “It was just such an easy connection,” Paul said, laughing as he recalled a memory. “Sarah does this thing when she first meets people, where she asks them questions like, ‘Tell me three things you like about yourself and three things you don't like about yourself’, and I was thinking, ‘What kind of question is that? This isn't an icebreaker.’ But the way that she asked was genuine, and that made me think a lot about answering the question genuinely as well.”

Another photo from our lakeside shoot

Although Sarah and Paul were both previously married, their experiences had been wildly different. Paul’s first marriage began shortly after he returned from his Mission, a Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (referred from here on out as LDS for brevity) custom where recent high school graduates, usually men, are sent somewhere in the world to proselytize. “I had friends who went to Mongolia, or Romania, or Spain and Argentina, “ Paul shared. “I was from California, and I went to Arizona. So I was really bummed out.”

He spent the first few months of his Mission in immersive Spanish-language lessons. “I was called to do Spanish-speaking on the border of Mexico, and I was there for two years, all day, every day, wearing a white shirt and tie, and talking to people about the church.” I asked what people’s reactions usually were to them. “Most people are really not that mean. They’re like, ‘Thank you, but no thank you.’”

Paul (right) with one of his companions while on his Mission in Arizona

“Over the first few weeks or months as a new missionary, you do learn about rejection, and it's hard at first, but honestly, you have a message that you feel is important, you want to share it with other people, and if they don't want to listen, that's their choice. But for those who are willing to listen, even just for five minutes, that’s awesome, that’s exciting.”

Paul continued. “You’re only 18, and you don't have a lot of worldly experience, or knowledge. But as you meet people and talk to people every single day for two years, you get to hear a lot of stories. You get to learn a lot about other people on how they live in the world. It makes you think about what you want for your life, and how you want to live it”

Paul (second from right) at a dinner while on his Mission in Arizona

Sarah jumped in. “This project”—Portrait of a Young Couple—“is like your missionary experience, isn’t it?” I thought about it for a moment, and found her comparison to be apt.

When Paul returned from Arizona, he enrolled in a local community college, met a woman at church, and married a year later. By all accounts I heard, they generally had a healthy marriage, but she stopped attending the Church soon after they were married.

“My ex-wife didn’t grow up in the Church. When we first met, she had just joined, and after we got married, she decided she didn’t want to go anymore. I had family members that were trying to convince me to get an annulment or divorce, and other friends who told me I was ‘so brave’ to stay, but to me, I had made a promise with her and with God that I would go through hard times and be with her no matter what. So I stayed, for 10 years.”

One of Paul’s high school senior photos, a few years before his first marriage

What eventually prompted the divorce was a planned move to the Midwest, where life would be simpler and a home more affordable. They’d been in San Diego now for the better part of a decade, and were tired of how expensive California was. Paul’s company would even allow him to move to the office in Indianapolis and keep his same salary. But the move prompted more conversations about what they each wanted in the long-term. Both wanted a family, but she didn’t want one with someone who held different religious beliefs.

As Paul described it, “We parted ways.” The two separated on very good terms. So good, in fact, that when he and Sarah first started dating, and Sarah still had lingering fears from her previous marriage about someone hiding their true personality, Paul offered that Sarah could talk to his ex-wife, essentially as a reference. Sarah took up the offer, and got a glowing reassurance. “She was just like, yeah, great guy, best guy ever!” Sarah told me.

Where Paul’s marriage ended amiably, Sarah’s ended far from so. That she’d had kids, and divorced, was something she’d sworn to avoid, growing up in Indianapolis. “I was a party baby; my parents never dated,” she told me. “Have you seen that 70’s show?” I responded that I had, quite a few years ago. “Well, imagine if Donna and Fez had a baby. They were in the same friend group, and it was just an accident at a birthday party. So, I was my dad’s birthday present.”

Sarah and her father at the wedding

I asked Sarah about how her own upbringing by parents who were never together affected how she thought about her own life. “Here's the thing: my parents had children from multiple relationships, and I definitely was resolved that I would get married, and all my children were going to look the same, all my children were going to be the same last name, all my children were going to be in one home. My children absolutely would not have the childhood that I had.”

Sarah has seven siblings, four half, three step. She was the last child on her mom’s side, and the first on her dad’s, and thus “the middle-child who was never really treated like the middle-child.” “It was very frustrating, growing up, trying to figure out what you’re expected to do, and that constantly changing,” she told me. Her father’s home had two bedrooms for six people: adults in one, two of the kids in the other, a third on a couch, and Sarah, as the oldest child, in the basement. At her mother’s, she was the youngest, and with her older step-siblings already moved out for much of Sarah’s childhood, she had a big bedroom, complete with a walk-in closet.

Sarah and Paul with her parents, their partners, and some of her siblings

“There wasn’t really money to go around at either house, but I was treated so differently at each.” Sarah’s father is Mexican, though she qualified that by saying that side of the family was very “vanilla Mexican.” “My great-grandparents spoke Spanish, and they didn’t teach their kids Spanish. We do a Mexican Thanksgiving every year, and this past year there was someone present who could only speak Spanish. They actually called Paul in to translate.” Sarah smirked at the absurdity of it all. “Mexican Thanksgiving, where none of the Mexicans can speak Spanish, and Paul—who is legitimately just white—translating for everybody.”

As “vanilla” as he was, Sarah’s father did hold traditional views that Sarah, as the oldest daughter, was responsible for taking care of the house (cooking, cleaning, watching the other kids) if her step-mother wasn't around. “I was babysitting my four year old little brother for short periods of time since I was six years old,” she told me.

Sarah with her father

Her experience with her mom’s family contrasted sharply. “My mom’s side of the family is very… quirky,” she said. Similar to her dad, Sarah’s maternal great-grandparents were the ones who originally immigrated to the US, in this case from Norway and Germany. “My mom was born in Wisconsin, and would tell people she was mixed, because she was half German and half Norwegian, and that was considered taboo at the time. So, when she moved to Indianapolis, where there's a lot larger Black population, and she was going to schools where she was one of the very few white people, and telling all these Black kids she was mixed, she got… looks.”

Sarah and her mother figuring out how to put on a set of nails

Sarah moved around a lot as a child, first from the inner-city, then to suburbs, and eventually to a rural town, and to her it felt like culture-shock each time. She was bullied occasionally for having a Hispanic last name (“They didn’t even do it because I looked Mexican; just because I had this name,” she said, incredulous that people could be so illogically prejudiced) and while her parents didn’t put expectations on her, she put them on herself. She played violin, joined the Mathletes team, and studied well, among other things. “I didn't like to be the center of attention though, which is something that my parents threw at me a lot because I was very dedicated at what I did. They would call me the family star, put me on a pedestal that I didn't have any interest in being on. A pedestal that still hurt to fall off of.”

Sarah in her baseball uniform; Paul happened to have a similar photo of himself

Her hard work did, however, pay off; Sarah received a full ride scholarship to Indiana University. She had a few ideas of what she wanted to do growing up. “I was really interested in languages, having taken several different ones in school, and so for a while I wanted to be a translator. I also wanted to start my own business, and I wanted to go to cosmetology school, because that’s the kind of career where how successful you are is in your hands. Plus, I would get to learn awesome tips for hair and makeup. I thought about massage therapy for the same reasons, too.”

Her father shut down the ideas. “He was like, ‘So, recently, you’ve talked about wanting to be a translator, massage therapist, and cosmetologist, so what does that mean? You’re going to be, like, an exotic Spanish-speaking masseuse, who has really good hair and makeup? I don’t think so.’”

Sarah (center) in her early day at Indiana University

Sarah started a major in “therapeutic recreation,” which she said sounded “fancy enough” to please her parents. Her priorities on campus quickly shifted to religion. Sarah had grown up exposed to many different faiths (she was baptized Baptist at age 5, her dad was Catholic, her grandmother and her partner Buddhist and Jewish, and she studied as a Jehovah’s Witness from ages 10-12) but converted to the LDS church after a college party made her reconsider her friends and faith. “The party was way too loud, so someone called the police,” she told me. “Everyone was running out, and there were these two guys carrying this girl who was really inebriated. They set her down on the concrete, and then just started leaving.”

Sarah looked to her friends; all but one just shrugged and ran off, nervous about personal repercussions of being caught drinking underage; scholarships, angry parents, the like.

Sarah with Nishant, her one friend who hadn’t run off when she was taking care of the girl at the party. They’re still friends today

“I turned her over, and she vomited in my hand,” Sarah continued. “Then I took my cardigan off, put it over her, and sat waiting until the police and ambulance came. I was the only person there with her on scene when everybody showed up, so I relayed information, and they told me to go home. My walk back was, like, four miles, and I was barefoot, too.” (Sarah had also been drinking, and apparently lost her shoes sometime earlier in the night.)

"I went to bed thinking about how, like, if I had been hurt, they would have all left, because other things were more important to them than taking care of another human being. And I wanted new friends. Even if they weren’t perfect friends, like, at the very least… don’t leave me to die.”

Sarah thought back on her friends from the churches she’d attended growing up, and started joining faith-based groups on campus. Most were in their “building phase,” and as she described it, “just cared about the numbers; no one even asked my name.” But a pair of missionaries—“Two of me!” Paul chimed—were on campus, and asked if Sarah would be interested in talking to them.

Sarah with a friend during college

“I prepared beforehand,” Sarah recounted. “I went back and I talked to my roommate, and we compiled a list of questions to try and stump the missionaries. Before I left, she was like, ‘Okay, be careful!’ And I replied, ‘Oh, don’t worry, it’s not like I’m gonna actually join or anything.’”

Sarah thinks her missionaries were probably the happiest, because she was the easiest convert they’d ever had. “All of the things I learned growing up, and all of the different religions that I had been around, this was like, all of the best parts of the things that I felt were right.”

“With Baptists and Catholicism, I could never get an understanding for the Trinity. Jesus was praying to someone, not himself; He called out for his father when He was in pain.” (The LDS church has a very different view of the Trinity than other Christian denominations.)

Sarah also hadn’t understood tithing going to someone’s salary. “Jesus and his Apostles were certainly not paid to preach, and lived essentially as nomads, eating what they could find along the way. It was more service-oriented and much less an organization.” (Positions within an LDS ward are unpaid; members are assigned callings and expected to give their time freely to perform the associated duties.)

Lastly, with Buddhism, “What I knew of it is that it’s of love and loving the Earth, and that there is a sense of everyone and everything working together in this symbiotic relationship with one another. Everything is connected, and what you do holds impact.” (I couldn’t find a specific doctrine about this for the LDS church, but it’s not hard to imagine Sarah’s missionaries speaking to similar ideals.)

Sarah with her missionaries before her baptism

Soon after, she met a man in church, and after a brief courtship, the two married during Sarah’s sophomore year. There were red flags from the start, according to both her own telling and that of her parents. Kevin, Sarah’s step-father, told me, with the signs of a past fury still burnt into his expression, “He respected me, because I was a man, but he didn’t respect her, because she was a woman.” Kevin and Sarah’s mother had found out about the marriage through a Facebook post. Her mother added, “Sarah was his second marriage, and he clearly had anger management issues.” Still, Sarah had fallen in love, and ended up giving up her scholarship at Indiana to move with her new husband to Idaho, where she transferred to the BYU campus there.

Content Warning: Domestic Abuse

Domestic abuse is disturbingly common. Officially called Intimate Partner Violence, or IPV, by the CDC, it’s defined as “abuse or aggression that occurs in a close relationship,” and exhibited as “physical violence (when a person hurts or tries to hurt a partner by hitting, kicking, or using another type of physical force), sexual violence (forcing or attempting to force a partner to take part in a sex act, sexual touching, or a non-physical sexual event when the partner does not or cannot consent), stalking (a pattern of repeated, unwanted attention and contact by a partner that causes fear or concern for one’s own safety or the safety of someone close to the victim), and psychological aggression (the use of verbal and non-verbal communication with the intent to harm another person mentally or emotionally and/or to exert control over another person).” It occurs in nearly 1 in 5 women, and 1 in 7 men, at some point in their lifetimes, and the long term consequences on physical and mental health can be catastrophic.

Sarah experienced many of these things in her first marriage.

In retrospect, she's able to point to many of the early signs of an abusive relationship. Moving to Idaho meant Sarah was away from any support network she might’ve had, and the worse her marriage got, the less she felt like she could reach out to someone. “I was too ashamed to tell my family, because I had given up my college, basically, to get into this relationship, and then it was just a big mess,” she said. The longer she waited to reach out to any of her family or friends, the harder it became.

Sarah stayed in the marriage for five years, both in hopes that things would get better, and because she often felt emotionally, financially, and physically unable to leave. She had two sons at this point, and though she and her ex-husband had tried counseling, things progressively became worse. (She asked to keep the details private.) Sarah ultimately ran away with her two sons in the hopes that things would finally change. (They didn’t.)

Sarah described the next few years as the hardest in her life. With her boys in tow, she got back an old job as a swim instructor at the YMCA, and though she worked hard and enjoyed her role, life kept dealing personal blows; Isak was being kicked out of preschool for aggression (“He was old enough to be impacted by the things he saw between his dad and me”), her best friend in life stopped talking to her (“It was so much worse than the break up with my ex; we had been through deaths, marriages, breakups, babies, college, and learning childhood and adulthood together”), and the divorce proceedings were drawn out and messy (“The paperwork got typed up wrong on one occasion, and there was yelling at court on another.”)

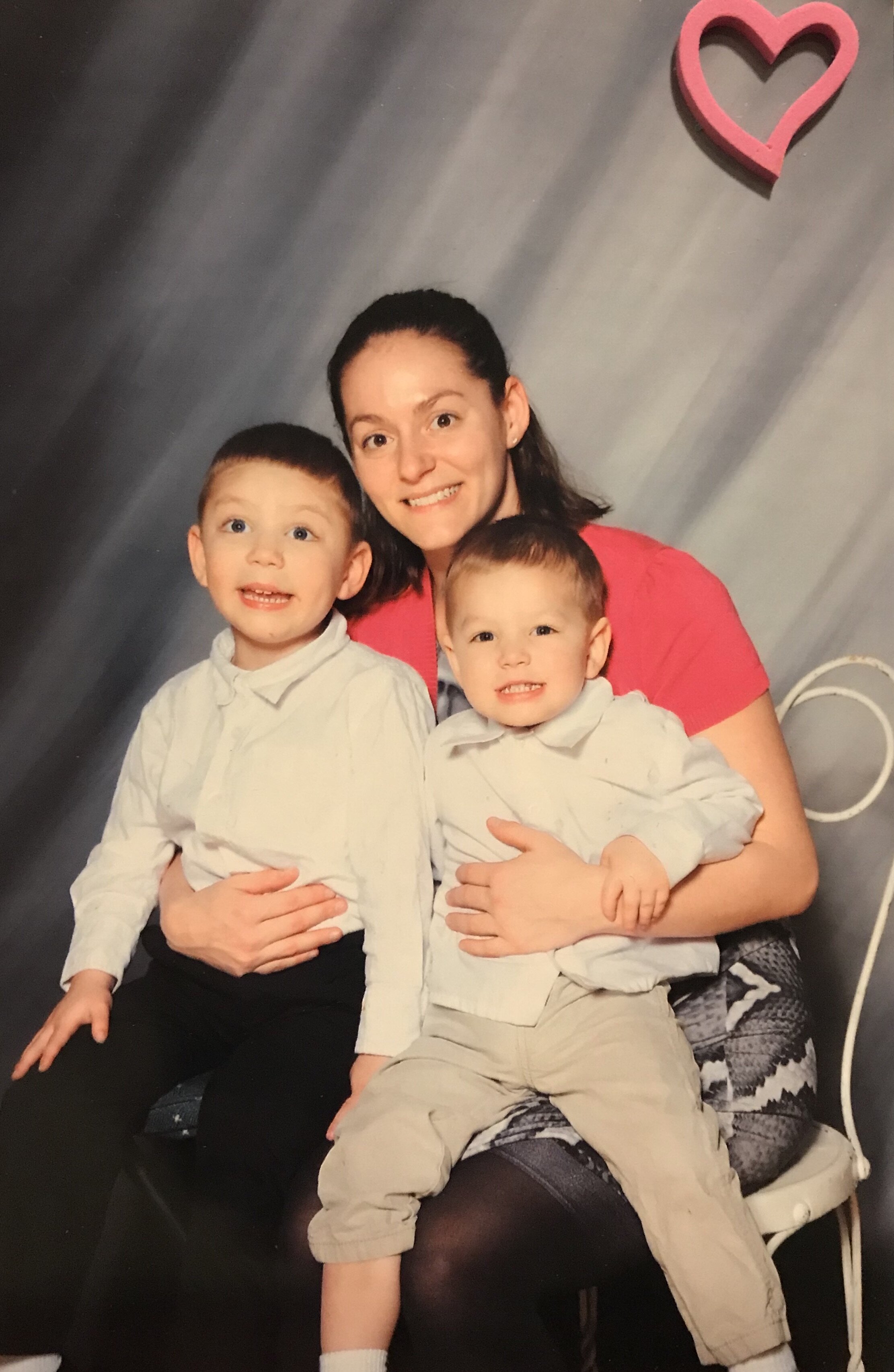

Sarah with Isak and Jakob. She commented, “I feel like you can tell I was having a rough time.”

A number of things helped Sarah through the period; the rekindling of her faith was a big one. But greatest of all was a realization that, as she put it, “life is not meant to be spent in isolation, in fear, in sorrow, but to be filled with loved ones, in joy and in peace.” When she reached back out to friends in church and her family, they were waiting. “My brother, his wife, and I had a conversation where I told them everything that had been going on in my life and my brother told me, on the note of suicide, that he needed me here, and then he just hugged me. Forever will I treasure that memory.”

“I had also tried to do things by myself for years,” she continued, “and I had shut people out for a really long time.” Emotional transparency was absent in Sarah’s childhood, and she was the first person in her family to go to therapy, something about which some family members still scoff at her. But as she began opening back up to her past connections, she found a steady and supportive warmth. “They understood that I wasn’t just trying to be mean all the time; I was just dealing with my own issues and trying to overcome them.”

In the following years, she’s had more honest conversations with loved ones, and though she doesn’t sugarcoat the difficulty of what she went through, she’s grateful for how her story has given space for others in her life to open up about their own traumas and calling abuse out for what it is.

Sarah with friends and family

“I had been through so much in such a short amount of time. What I found from opening back up was that people cared about me and my family and that I didn't have to bare my burdens alone,” Sarah wrote to me. “I feel like there is definitely some purpose I’m meant to achieve with the knowledge I've gained, whether it’s just being a rockstar parent to my kids, or starting something really impactful to the community; I don't know, but I’m open and willing to be the tool I have painfully been molded into by our Heavenly Father.”

In our week together before the wedding, I found myself at times learning just as much from the two boys (Isak and Jakob, six and four years old, respectively) and their behaviors as from my conversations with Sarah and Paul. It’s been probably over a decade since I was around small kids for any extended period of time, and I’ve certainly never lived side-by-side with them before. (I was an only child.)

Isak and Jakob playing in the backyard while Paul mowed the grass for the wedding

There’s a question I often ask couples about how they’d like to raise their kids (if they want kids at all) and typically the answers are very reflective, thoughtful adages about certain values they’d like to impart, or not impart; virtues like patience or strength, environments like a stable home. But that question, in so many ways, felt irrelevant here. Values are wonderful guideposts, but more of the energy spent raising a child is devoted to daily disaster mitigation than to reflective lessons given at just the right moment. More than a few times during my stay with Sarah and Paul did our conversations get cut short by the sound of either Jakob or Isak screaming at the other for some unforgivable sin they’d just committed.

Jakob and Isak playing in the living room before dinner

The two were unflinchingly honest. A few nights before the wedding, I spent some time making dinner—Taiwanese beef noodle soup and scallion pancakes—as a way to both share a bit of my own culture and to take a burden, however small, off of Sarah and Paul’s shoulders. When the boys sat down in front of their little bowls of soup—broth, some noodles, one piece of beef each, an egg, and some bok choy—they took a sniff of the strange new food and looked quizzically at myself and then Sarah and Paul. “I don’t want to eat this,” Isak said, after a bit of a pause. “It smells strange.”

Jakob (trying) and Isak (not) the Taiwanese beef noodle soup I made for dinner one night

Sarah took a compromising tack (“You have to at least take a ‘no-thank-you’ bite,”) while Paul expressed things in lesson-like terms (“When a guest makes a meal for us, we don’t say it’s gross, or say it’s weird. We say thank-you, and try it, and if we don’t like it that’s ok.”) Sarah apologized on their behalf, though there wasn’t a need; it was reward enough for me to watch the two puzzle over the new smells.

Later that evening, after Sarah and Paul finished putting the boys to bed, Paul told me about what being a stepfather was like. “I knew I’d be a father someday, but I didn’t expect it to be like this,” he admitted. “It’s been hard, because I have not been in their lives. I’m not their dad. I’m not even their stepdad, yet. Their dad legally still has the right to make decisions with Sarah about them. How should we raise them? How should we discipline them? Technically, at this moment, I still have no say.”

Paul tickling the two boys as they all got dressed for the wedding. They’d all just recently moved into the home, hence the u-haul boxes

I witnessed some of this myself; a common excuse the young boys had for doing something Sarah and Paul didn’t like was, “Well, our dad lets us do this at his house!” Often, it was just an impulsive lie, something they said to try and get out of trouble. But the sentiment remained clear: “I don’t have to listen to what you say, because you’re not my dad.”

“It’s a hard transition, becoming a part of a family that already exists,” Paul told me. “It’s learning how to raise kids when they’re already four and six years old, and you don’t get to start when they’re newborns. You don’t get to learn with them.”

Still, there are many moments of love and reward. “I feel like they grew to like me pretty quickly,” Paul said, looking at Sarah for confirmation. She nodded, and added, “The second day he met them, they were like, ‘Mom, are you gonna marry him?’ Because even though they’re young, they’ve been taught that if you’re in a relationship, it’s taken seriously.” The boys have also accidentally called Paul “dad” before, though they always correct themselves right after. “They say it accidentally for a reason though,” Sarah mused. “Because that’s what feelings are evoked. Fatherly feelings.”

Family portrait

Faith has been near or at the center of Paul’s entire life. His parents, both also members of the LDS church, grew up in central California, a heartland for American agriculture. They married young, and had five children; Paul was the middle child. He remembers his parents instilling hard work from an early age. “We had a family paper route growing up,” he told me, “and by the time I was a teenager, we were waking up at 3:30 in the morning and delivering 250 papers.” As one of his siblings described their financial situation to me, “we weren't super poor, but we definitely weren't rich.”

Paul (far right) with his family

Paul did always have a roof over his head, though, and a stable family and home. He described his childhood as being sheltered, yet normal, and is very much aware that he hasn’t gone through a lot of hardship, at least when compared to Sarah. “I watched Power Rangers and played video games. I played sports in high school, had my own car and did dumb things with my friends. But I never went through anything really bad. My parents were kind and loving and didn’t get divorced. We had a small but nice, safe home in a good neighborhood. We always had food. I had good friends. I had a very good childhood with many blessings,” he wrote to me in a later email. His parents raised him and his siblings within the LDS church and, save for one, they’ve all continued in their faith as adults.

A childhood portrait of Paul

Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or Mormons as they’re more colloquially known (the church has officially distanced itself from the term; whereas the old website was mormon.org, now they use churchofjesuschrist.org) are the subject of a lot of public parody. Part of that is because of its youth as a religion, having been officially established in the 1800’s, vs. in the BC era like most of the world’s other major religions; another part is because of the public and extraordinarily wide reach of the Missionary program, and subsequent satire therein. (One need look no further than the hit musical The Book of Mormon, written by the same folks who write South Park.) “We’re used to being made fun of,” Paul’s mom, Helen, told me, “and it’s been happening for hundreds of years. We’re honestly kind of a big target; we don’t smoke, we don’t drink, we get married young and we have lots of babies.” Compared to the violence directed towards members of the LDS church towards the beginning of its founding, the prejudice they experience now is relatively benign.

One thing that’s separated the LDS church from many other religions is its incredible organizational might. More similar to the Catholic church in this sense than in any Protestant denomination, the LDS church works within a set of hierarchies, vocabularies, and “rules” that to non-members may seem onerous, and at times problematic. Individual churches are called wards, the leader of the church the President, and significant resources are devoted to building temples, which are, to believers, monuments to the power and beauty of Christ, and, to critics, monuments to excess and exploitation.

(I found myself particularly curious about this last point one day when talking with Paul’s family. Overhearing our conversation, Sarah produced a hardcover book that detailed the building of the Indianapolis Temple. On the first page: “Why do Mormons build temples?”)

I visited the outside of the Indianapolis temple after the wedding to see what it looked like. The gate had a sign with some COVID information

When I asked Paul to share about what his faith means to him, he said the following:

“A long time ago, I realized that there is only one reason to go to church: because God said you should. I do believe in God. I know that He is real and there is a purpose for us on this earth. I don’t always understand everything about life, but I know that we are here for a reason.”

“Church isn’t always fun or even spiritual or uplifting. Sometimes it’s boring, confusing, tiring, or even frustrating. But I know that I’m supposed to go. I have gained a witness for myself that what I believe is actually true. And as hard as it might be to go to church sometimes; as easy as it could be to just give up and stop going, I can’t deny what I know.”

“Many people have stopped going to church. From what I’ve seen though, the people that had an actual knowledge of its veracity have usually returned.”

Sarah, Paul, and the kids one Sunday before church

Paul and Sarah originally planned to do a full traditional LDS ceremony, the most important part of which is the sealing ceremony within the Temple.

From the official Church website (lightly paraphrased for brevity):

In our Heavenly Father’s plan of happiness, a husband and wife can be together forever. The authority to unite families forever is called the sealing power.

Unlike marriages that last only “’til death do you part,” temple sealings ensure that death cannot separate loved ones. For marriage relationships to continue after death, those marriages must be sealed in the right place and with the right authority. The right place is the temple and the right authority is the priesthood of God.

Those who are married should consider their union as their most cherished earthly relationship, for a spouse is the only person other than the Lord whom we have been commanded to love with all our heart.

Paul and Sarah’s rings

When I caught up with them a few months later in September, their Temple had only just opened again for marriages; Sarah and Paul will have to wait a little bit longer to be sealed together for eternity.

Sarah and Paul both look forward to their future together, and when I talked to friends and family, all said how they had faith the two would build a joyful life together.

“When I think of Sarah, I immediately think of the word powerhouse,” Madi, one of Sarah’s childhood friends, told me. The two had gotten close as children through gymnastics. “She could just power through things that I would, like, almost break my neck over. If she lands hard, she gets back up and still hits it with power, whether it was her floor routine or just her life now as a mother. I hope that her boys can take away how strong she is.”

Sarah during our portrait session

Paul’s older sister, Erica, told me, “I think Paul is just the sweetest, most loving man. It always made me super sad that like he never had kids, because he was always someone who loved playing with the kids at church. He’s gentle, caring, and still passionate about his beliefs, but he’s also just really cool and really chill.”

Paul helping Jakob do a flip before family portraits

Sarah and Paul plan to have more kids together in the future; Isak and Jakob have made it well known that they’re set on being big brothers one day and having a “plethora” of siblings. They just bought a house together, and during the pandemic have been staying at home, Paul working from a corner office in their bedroom and Sarah taking care of the boys during online school.

Sarah plans to go back to college sometime to finish up her Bachelor’s degree; business interests her, as well as better understanding finances. “My family has never been good with money,” she told me, “which makes learning about it all the more interesting. I’d be able to help my family, and perhaps one day become a financial counsellor for other companies’ employees, helping them with budgeting or planning for the future.” For now though, she is happy at home, and glad to be able to spend more time with Isak and Jakob.

Sarah and Paul’s wedding was the first that I photographed following the COVID-19 shutdowns imposed across the US in March 2020, and many of their choices have matched those made by the other couples I’ve photographed during the pandemic. Elegant venues have been replaced with family backyards, chef-crafted dinners substituted for homemade roasts, and, often, the pressure that comes with hosting an event with hundreds of guests switched for a much more relaxed, peaceful, and yet no less beautiful ceremony.

Sarah and Paul’s Bishop from the Church hadn’t been allowed to attend or officiate the ceremony, so one of Paul’s friends conducted it instead, in the presence of about two-dozen family and close friends. It began with Sarah being walked down the aisle by her two sons, hands held tight on either side.

Sarah walking down the aisle with her two boys

After the ceremony, Sarah and Paul posed for some photos by the small neighborhood lake, cut a cake made by a friend from the Church, and rode off on a motorcycle for their mini-moon in downtown Indianapolis.

(The only thing Sarah wished they could’ve had was dancing; she’d actually majored in dance at one point during college, and it’s been a few years since she’s been able to properly show off her talent.)

Perhaps my sample of couples participating in this project is somehow skewed; perhaps I’m reading too much into people’s psychologies and emotions; but my genuine belief is that most couples, despite planning weddings which look nothing like those from before the pandemic, are actually happier with the result. Smaller weddings have allowed for more time spent with every guest, far less stress to act or look a certain way, and, of course, huge savings for those who may have otherwise spent tens of thousands of dollars but instead spent just a few hundred.

This isn’t to make light of the many hearts broken or dollars lost by couples cancelling or postponing their weddings due to COVID-19. But, if there’s any silver lining amid all the chaos and grief this pandemic has caused, it’s this: even if you can’t have the wedding you dreamed of, you can still marry the person of your dreams.

COVID is not the only thing in the air.