Michael spent his 20’s in prison and solitary confinement; Shannon spent hers pursuing a career in film and traveling the world. What binds their stories together?

Shannon + Michael // Charleston, South Carolina

Beneath the soft, wispy shadow of a thin layer of clouds covering Summerville, South Carolina, in the field next to the church where Shannon's parents serve as pastors, Michael raised a microphone to his mouth and recited his vows.

Michael reciting his vows

"Shannon... I can remember a time where I envisioned what my future was going to look like," he began. "I had some ideas about who my future partner would be, and I thought that because of choices that I made in the past, I was gonna have to settle on some level. But I was fortunate to meet you, and the passionate individual that you are, who just loves and trusts people."

Michael spoke from his memories, without notes or a script. "I think what's beautiful about our relationship is watching our impact on the people on the edges of our social circle, like Darrel"—a homeless man whom he and Shannon often spoke to and helped—"and all these other people we care about. That's the kind of impact that we have. I just love you so much, and I cannot wait to spend the rest of my life with you."

Michael looked longingly at Shannon as he lowered the microphone and gently handed it to her. Shannon, too, spoke from her memories, aided by a set of notes she read from her phone.

Shannon reciting her vows

"Michael... I have imagined various outcomes for my life. And our life together has been far beyond what I imagined. I truly didn't expect to actually find someone who is just as fearless, just as curious as I am. Someone who cares about creating meaningful memories and interactions, and recognizes, as I do, that those moments are the most significant. Though I could visualize being with a partner one day who might be willing to drop the expectations, limitations, and norms of society for solace—in a tiny home village, a container home, a homestead in the country or the mountains—I could not fathom finding not just willingness but the desire for such a move in you."

Shannon reciting her vows

"I look forward to our future adventures as we commit to forever together. I look forward to picking up more hitchhikers, knowing that they will become family to us after the ride. I look forward to finding some other special hole in the wall to hang out; to creating new adventures and traveling the world together. I can't wait to continue dreaming with you, and making those dreams a reality. Growing with you, and ensuring that growth is our goal."

Michael reacting to Shannon’s vows

"While I express my anticipation, I am also full of gratitude; gratitude for your care, your thoughtfulness, your encouragement, your forgiveness. I am grateful for our first conversations that made it clear to me that you will be as real and honest with me as I will be with you. I am grateful for New Year's parties,”—she and Michael met at one—”and for the continuous fun that we have together. I'm in awe of your resilience. I will always share your support and will always appreciate that you're everyone's hype man." A chorus of chuckles rose from the guests who understood how true this was; how genuine Michael’s enthusiasm was for others' passions and dreams.

"I am truly so in love with you, Michael. And I promise to be your best friend, your confidant, and your accountability partner. I promise to love you, and I will try my best to choose patience every day. I love you, baby."

Shannon and Michael holding hands during their ceremony

Shannon and Michael's individual stories are built on wildly different foundations. Shannon grew up in a stable, loving home with no concept of the limits to her potential. She spent her twenties pursuing a career in the film industry and traveling the world. Michael grew up inquisitive but never nurtured, exchanging what he felt was dull stability for an "exciting" freedom in the form of crime and drugs. He spent his twenties in and out of prison, often in the 75 square feet of a solitary confinement cell, wondering if he'd even live to see a "real" form of freedom again.

Shannon and Michael on the wedding day

But despite those contrasts, Shannon and Michael's love story is built on notably similar values: how they approach new people free from judgment and full of inquiry; how they live in the present, untethered by past insecurities or future worries; how they value intellectual and emotional honesty; how they care about social justice.

For the few days I spent with them before their wedding in early March of 2021, I saw how they embodied these values. Their home, a narrow two-story loft, was small but cozy, with their bedroom at the top of the stairs and their living room, kitchen, and tiny bathroom at the bottom. Their cat, a thin siamese named Blair, roamed freely between floors, often curling into the dark recesses of the shoe and coat racks near the front door, her occasional hops between tables and the ground the only sounds that punctuated the otherwise quiet air.

Shannon and Michael’s cat, Blair

Soon after I arrived, I asked Shannon what the schedule for the week looked like. She patted her head and pulled out her phone, showing me a photo of a Black woman with a beautiful and intricate hairstyle. "So this is what the end result is supposed to look like," she said, "with bantu knots up front, and some extra stuff in the back." The process of achieving that look, she explained, would take 12 hours across three days of washing, straightening, extending, tying, and accessorizing her hair.

Shannon’s sister, Sydney, helping do her hair

Shannon spoke with a bit of unease; she told me about how she rarely felt comfortable with changes to her appearance. "I gotta be honest, I feel very awkward about things to do with my hair," she said. "I don't feel very comfortable when people do it, or with branching out and doing anything different. I usually keep the same style for, like, five years at a time." (Most recently, after a decade, she'd stopped relaxing her hair, and let it grow out in its natural, dense curls.)

Shannon’s hair on the wedding day

When I asked the same question to Michael about his schedule for the week, he replied with joking incredulity. "People ask, 'What else do you have to plan for your wedding?' And we're like, literally everything. We don't know what we're doing; we've never planned a wedding before!" It helped, then, that their wedding would be small, with just 20 guests and a small after-party for their friends and siblings at a pretty cabin they rented on AirBnB.

Shannon and Michael’s ceremony site, with socially distanced chairs for around 20 guests

Both worked for most of the week before the wedding, Michael at a local power-washing company where he travels around the area meeting new clients and providing quotes, and Shannon at a local nonprofit called Meeting Street Schools, which runs a set of PreK-8th grade schools in Charleston that provide high-quality education to children in under-resourced districts.

One evening, when Shannon and Michael returned from work, we went on a walk around the neighborhood, an area called Cannonborough in downtown Charleston. They told me a bit about its history; that the land we walked on used to host much of the city’s small community of rich, free, Black people in the 1800’s, and pointed out buildings that used to be all-Black schools in the 1900’s. They also talked longingly about their favorite music venue nearby, a vintage jazz club called The Commodore, which was closed due to COVID. "It has very low ceilings, a lot of swanky lights, and a bunch of fog machines," Michael described to me. "It's literally a whole 'nother world there. Like a club, but with a live band.” Weekdays, he said, were the best time to go, when college students who packed in on the weekends yielded to friendly locals of all ages and backgrounds.

Inside the Commodore. Credit

Another evening, after we'd finished dinner at home, Michael insisted I watch (and he re-watch, for at least the fifth time) Between the World and Me, a movie based on Ta-Nehisi Coates' book of the same name, written in 2015 as a letter to his son about his "experiences growing up in Baltimore’s inner city and his growing fear of daily violence against the Black community." In the movie adaptation, Black actors, celebrities, and activists—Mahershala Ali, Janet Mock, Jason Moran, and Oprah Winfrey, to name a few—read excerpts from the book, their performances set to a rolling soundtrack that oscillates between frenzied drumlines and tranquil piano meditations.

Trailer for HBO’s Between The World and Me

I watched, and Michael listened. He closed his eyes and raised his hands as if responding to a pastor's sermon, whispering along to one of his favorite scenes, a passage recited by Mahershala Ali about bygone romance. Breathy pauses lingered between each of Ali’s lines, and the actor’s eyes shone glossy with tears:

"My second year at Howard, I fell hard for her. A lovely girl from California, who was then in the habit of floating over the campus in a long skirt and headwrap. Her father was from Bangalore.

And where was that?

I remember my ignorance. I remember watching her eat with her hand and feeling wholly uncivilized with my fork. I remember her going to India for spring break and returning with the bindi and photos of her smiling Indian cousins.

I told her, N****, you Black. Because that's all I had back then. In my small apartment, she kissed me and the ground opened up.

How many awful poems did I write about her?

She was to me a galactic portal, off this bound and blind planet. She held the lineage of other worlds in the vessel of her Black body."

Shannon, who studied film in college and worked in the industry for a few years, often lamented to me that Michael had a general apathy towards movies. But this one had made an impression on him, and I watched as she quietly stared at Michael, holding a smile as soft as a pillow as the music and words guided Michael between quiet reverence and fierce emotion.

Shannon now loves living in Charleston and building a life there with Michael. But for a time during and after college, she found her home city too small and tedious, a product, perhaps, of her parents' lessons in unbound ambition. "My dad used to always say, 'With God, nothing's impossible,'" she told me, "and so I grew up with both of my parents truly making me believe I could do anything."

Shannon with her mom and dad

When I talked to her parents, Shann and Celeste, about that attitude, Shann told me, "Celeste and I had a massive desire to give the kids every opportunity possible. If they found a hole on their shirt, we were like, let's invest in a sewing machine so they can learn how to fix it themselves. Or if they started to dance on their own as kids, we put them in ballet." He chuckled, and joked, "Shannon played basketball, and oh my God, I was about ready to buy her a basketball team!" They nurtured her curiosity, and prioritized growth over perfection. (One of Celeste's favorite phrases was "it's all in the recovery"; mistakes were simply deposits made to the bank of future wisdom.)

Shannon when she was a baby

The family also revered their faith; Shann was the lead pastor of the church he founded, and Celeste was the associate pastor. Amid that theological pedigree, Shannon also grew up deeply religious. "I definitely absorbed what I was learning and felt as a child," she told me, "and that I was a leader in that space."

In retrospect, Shannon told me that her faith sometimes felt overly laced with pressure and performance. "People are automatically looking at the pastor as their leader, which makes their kids looked up to, too," she said. "As a pastor's child, it's like the spotlight is always on you. People are always watching, even if you don't recognize it. They're talking about you, even if you're not paying attention." She told me about how sensitive she was as a child: quiet, reserved, the kind to enjoy playing by herself more than joining other kids, and how that sensitivity didn't always harmonize with her perceived role in church.

Shannon with her father and mother

Many of these realizations have only appeared now that Shannon is older; as a child, she carried her various identities without much concern or understanding, until she entered a new school in 6th grade called Ashley Hall. The first time Shannon mentioned it, she quickly said its name and moved on before Michael interjected and insisted she elaborate. "Tell Vincent more about it!" he said, his hands outstretched and shaking with enthusiasm. "How it wasn't just a private school, but this, like, utopic white space for girls who played tennis!" He chuckled at his offhand description, but Shannon sighed lightly, seeming to agree.

Drone photo of Ashley Hall, in the foreground. Credit

Ashley Hall is an all-girls private school for Pre-K to 12th grade students located in downtown Charleston. Its class sizes range between 40 and 50 people, and its tuition spans $18,000 to $29,000 a year. Shannon told me of early contrasts she observed when she first began attending. "It's smack dab in the middle of downtown, and it's kind of wild to see. It used to be an estate, and all the buildings are, like, these super old giant mansions. You would walk just a couple streets down, it would be these really rough-looking areas. And there was no interaction between these two spaces." (The school was founded in 1909, but didn't graduate its first Black student until 1976; its most recent graduating class of 2021, pictured on the homepage at the time of this writing, appeared to have no Black students, despite the wider population of Charleston being around 20% Black.)

Shannon's parents first heard about the school through another Black family who had sent their child there. They told them about the financial aid and college scholarships Shannon would likely receive upon graduation, and persuaded them to have Shannon apply and ultimately enroll in the school.

Shannon's relationship with Ashley Hall is striated, like a zebra, with bright, positive streaks positioned alongside intensely negative emotions. The positive memories she had from her time as a student often centered on the way it nurtured a sense of educational freedom. "I had never really been in an educational space that I felt was also my home," she told me, "where I could just have my own little corners or spaces to go by myself at random times." She excelled as a student, winning academic awards, playing for her basketball team, and being elected class president.

Shannon, center, at Ashley Hall

And yet there were also roots of an unmistakable discomfort, emotions she admitted to me she couldn't fully describe until after she'd graduated. "The epiphany I had during that time was more around class differences,"—she was one among few who attended with financial-aid—"and it wasn't until after that I really felt the racial stuff."

She shared a story about her great-grandmother. "Her last name was Ravenel, which comes from her family's history of being slaves for one of the wealthiest old Charleston families of the same name. That family's kids were in the grade above me... and that was just really… weird." She talked about how her great-grandmother, in the late 1950’s, used to drive a white family's child to Ashley Hall but was never allowed to enter the school gates. The first time she stepped foot on campus was at Shannon's graduation.

Shannon, right, with her great grandmother

Perhaps this story can be interpreted as one of progress; that Shannon could graduate from a school with academic honors and as class president, when decades earlier her great-grandmother wasn't even allowed to step foot on campus because of her skin color is, at minimum, an improvement. But it is undoubtedly also a story of pain, fuel for a sense of doubt and confusion Shannon had about whether she belonged in such a space. "I couldn't really explain those feelings back then," she told me, "but I've now had the opportunity to sit in administrative meetings and be able to say, this is what it felt like for me as a kid whose great-grandmother couldn't even set foot on this campus. So how can we change it so that the experience isn't like that for another Black child in the future?"

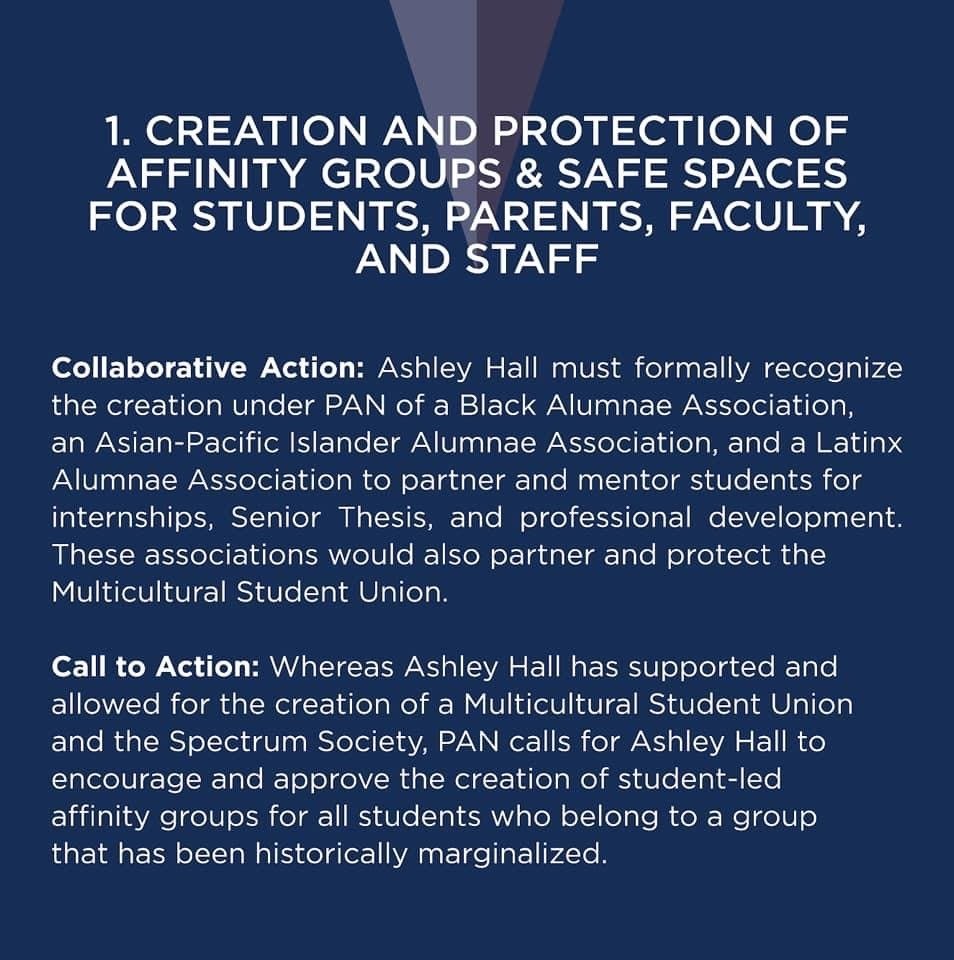

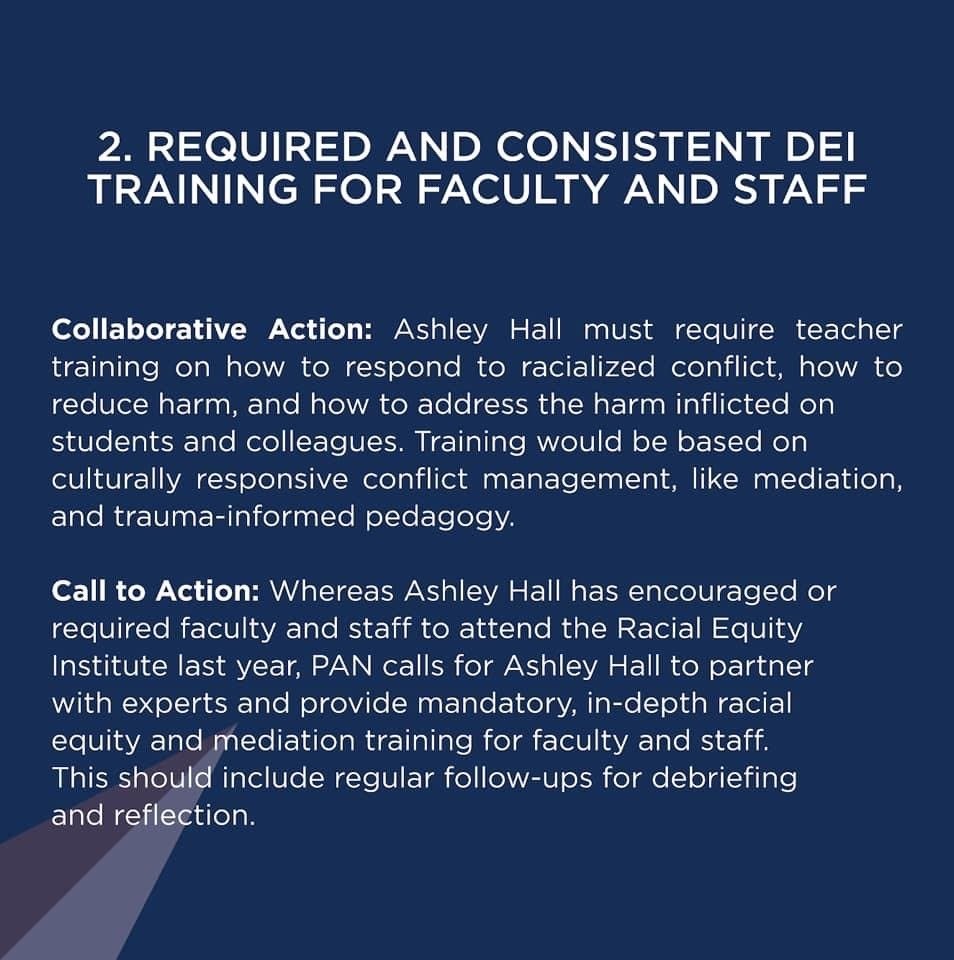

In the aftermath of George Floyd's killing in the summer of 2020, Shannon helped organize a letter, signed by over 300 alumni, teachers, and parents, asking for the school to, “lift up and push forward a new culture that centers BIPOC voices and readies all students for global higher education.” “We were thinking, let's do something. Let's push the administration. Let's put pressure on them. Let's hold them accountable. Let's change that place. Because this has all been about creating a sense of belonging in a space where we never had it, so that we can heal and let go of this. Because it feels like an albatross on me.”

The five points that Shannon and other alumni demanded of Ashley Hall’s administration

Attending college was always a certain step for Shannon, and she knew early on what she wanted to study: screenwriting and film. "I was extremely passionate about it, and quite ambitious as a young kid," Shannon told me. "I wanted to create, and I knew I was fascinated by people and their interactions."

Shannon's dream school was NYU, well-known for its lauded film program. When she applied and wasn't accepted, she was crushed, but what took its place, she thinks now, worked out for the better. She attended Virginia Commonwealth University, which required her to have a second major or minor. Shannon chose film for her first major, Sociology for her second major, and Anthropology for an extra minor. “I'm glad now that I have those other degrees, since I work in education now, not film,” she told me.

After graduation, Shannon worked in the film industry to chase her version of a Hollywood dream. On paper, her job was perfectly suited to her tastes and goals. She worked in casting, and learned to write better screenplays by reading a never-ending torrent of them.

Shannon working on a film set

In practice, though, she was overwhelmed. Even when she wasn't in the office, she was working, usually by reading and marking up mountains of scripts. "I was living with my boss at the time because I didn't have any money," she told me, "and crashing on friends' couches. I'd have these moments where I'd be working all day, and the moment I get off, ask, ok, where am I gonna go? Where am I gonna sleep tonight? Because I wasn't making enough to get my own place."

Shannon (center) directing her first film in high school

Her passion, she recalled with a still-burning tone, was "absolutely unreal," but working 18 to 20 hour days proved unsustainable. The final straw was a job offer that only paid minimum wage, and even less when she factored the extra hours she'd inevitably have to work unpaid. She broke, and quit, opting to pursue a career in education, first as a literacy tutor through AmeriCorps in Washington D.C. and then through a Master’s degree in Sociology with a Fulbright scholarship in the United Kingdom.

Those years, she recalled, were hard both in her career and in her personal life. For years, in part due to the unresolved traumas of her time at Ashley Hall, religious upbringing, and other struggles, Shannon lived with severe mental health issues. “There was one specific time when I was in England that was the worst of it,” she told me, “when I went radio silent for like, a good two weeks. I didn't go to my classes, or eat, or sleep.”

Shannon in the UK

Her relationship with her parents, too, had for many years grown tense. Looking recently through old journals and notes she took as a child, Shannon told me about how the philosophy she'd quietly crafted then combined Christian and non-Christian elements that formed less of a coherent worldview and more a sign of the early workings of a conflicted mind: The Creation, sin, multiverses, inner peace, anarchy. If everything was possible with God, then what limited existence other than her own imagination?

Over time, this philosophy of all things being possible, rooted in her Christian upbringing, began to conflict with it. "The biggest issues I had with my family were all around religion," Shannon told me. "Yes, they wanted their children to be confident, happy, and successful. And they also really, really wanted them to be Christian, not out of a place of coercion but out of love and care for us, because they really believed that was the best way to raise us."

Similar disagreements, she told me, came up as she grew older and broached subjects that seemed further and further from her Christian upbringing: anthropology, cultural relativism, dating, sex. Talking about all of these things with her parents at first created more discomfort, but over time the conversations formed the basis for a renewed relationship. "It was a time when we talked openly about my beliefs without any fear, and it was tough," Shannon said. “But after that time, my parents and I had a completely different relationship. I can tell them everything and anything now, and it's made us so much better." Her relationship with Christianity now, she said, is one that is distant from much of the theology and ideologies, but still respectful of the emotional experience. “I’ve become more open to connecting deeper to some aspects of it in the future,” she said, “and the role religion will play in my future does feel a bit more open-ended now than even a few months ago.”

When she returned from her Master's in the UK, Shannon’s mental health was at a low point, and being back in Charleston did not help. "I hated it when I first moved back here," she told me, "and it's still not where I want to be long-term. But I've found things that keep me here, where I want to make a difference." She smiled, and looked at Michael." Plus, he loves it here."

Although Shannon left the film industry in her early 20’s, the curiosity and interest in people’s stories that motivated her to pursue film in the first place continued to guide her life outside of it. One outlet she found was by going on dates. "I found a love for going on these random dates with strangers," she said, "and just having these extremely different experiences. How I'd react differently; how people would react differently to me." She likened it to a television anthology. "I was totally fascinated by these little interactions I had with all these people, and in my mind, it was almost like I was creating a narrative with a character that was me who interacted with these different guys each episode, and reflecting on what that experience was like." Michael, listening in on this conversation, shook his head. "That sounds like hell to me," he chuckled.

Going on dates also helped her process a breakup. Soon after she moved back to Charleston, Shannon’s boyfriend of seven years broke up with her. "It was so tough for me, because in my mind, this person was it. He was whom I was going to marry, have kids with, spend the rest of my life together. And then it ended. After we officially broke up, it was a super weird feeling. I just was not interested in thinking about a future with anyone.”

And then, she met Michael. Immediately, his story stood out to her. "Fascinating is not quite the right word, because his story is so much deeper than that. But he is the most fascinating person I've ever met. I feel like I have the most opportunity for personal growth with him, knowing all the incredible things he's done and his personal journey. I'm so encouraged and moved by it."

Shannon and Michael on their wedding day

Again and again, those close to Shannon and Michael told me about their unique connection. Shannon's father, Shann, told me, "It is such a beautiful thing to watch her and Michael have the same heart and passion about people in need or people that are the underdogs. You love, as a parent, that your child is marrying somebody that has that level of connection with the same heart." Michael's sister, Laura, said, "I thought, how could I not see this coming? This makes so much sense. Because Michael's the same way as Shannon. He's not surface level, always trying to dive deep, and to really understand what's happening around him, what his role in it is, and how he can help."

I've been thinking recently about how different couples connect with one another through different periods of life. Some connect through their pasts; perhaps they've both experienced the same traumas before, and through that find a unique emotional link. Some connect through their presents, sharing time together that only they could have shared. Some connect through their futures, holding common goals and dreams and ways they plan to achieve those. And some, like Michael and Shannon, connect through all three.

Michael and Shannon on the wedding day

Content warning: self-harm

When Michael first shared about his life with me, he prefaced with a few words. "This is a unique thing for me, because other than Shannon, the people around me don't really know much of my story. I don't ever really talk about it."

Michael was born in Charleston to a home that wasn't so much broken as it was never put together in the first place. His parents married when they found out they were pregnant with Michael, then divorced when he was two. Each remarried soon after, his father into a bit of stability, his mother far less so.

Michael as a baby with his mother and father

Michael when he was a child

Michael was always an inquisitive child, with a curiosity that often got him in trouble when he disassembled electronics and appliances to see how they worked. "I loved figuring out the way things worked," he told me. "But a lot of the adults around me on my mom’s side just wanted to drink. They'd yell at me like, 'Why did you do that? Quit it!'" He wondered aloud how the rest of his story may have unfolded if his family had been like Shannon’s, breaking ceilings and clearing paths so Michael could chase his interests and dreams. "Man, if that curiosity would have been cultivated from a young age, in a stable home, a loving family, where I wouldn't have been the oddball all the time?” Michael shook his head and let out a big sigh. “There's no telling what I could have done."

For a time, he filled the missing encouragement with a desire to do well in school and please his teachers. "I was a teacher's pet more than anything, and I was at the top of my class each year,” he told me of elementary school. He won spelling bees, often appeared in his school's newspaper, and made honor roll each year.

Michael (center back) with his family on his father’s side)

As he grew older, Michael inherited his mother's free spirit, and as little as he had there, he always gravitated towards his mother's life over his father's. "I preferred my mom's side," he told me, "pretty much because she let me do whatever I wanted to do." His mom moved constantly. "I went to a different school almost every single year because I was always moving," he said, "and my mom was always moving and going to different men in different places around town. So I was just never able to really have, like, a friend group."

When I talked to Michael's sister, Laura (the two have the same father,) she recalled her memories of him as a younger child. "Michael and I have always had a good connection, where we just get each other. But when he was a kid, he was very, very angry. There really was this, like, cloud of anger and frustration and tension around him."

Michael with Laura

At one point, Michael and his mother had moved into a trailer in what Michael described as a "redneck neighborhood, in a really nasty house with bugs and everything." "She was seeing this rich guy," Michael said, "and turns out they were doing a lot of coke together. I already wasn't going to school half the time, running wild for months. And finally, my mom told me I had to leave to be with my dad in two weeks, because she couldn't take care of me anymore. And I didn't want to leave."

Before he left for his father’s home, Michael told one of his friends that he wanted to try smoking weed, thinking he wouldn’t have the chance to again once he moved in with his father. "I'll never forget this night," he told me. "This night changed my life forever." His friend called in an older sibling, who pulled up in a black Jaguar with tinted windows and a booming sound system. "I got in the car, and they had a blunt rolled up already. We were listening to Master P, and they turned the music up really loud. And man, I smoked a lot. And I realized: this is what I want to do. This is it. I'd tasted the dark life, where we were being bad on purpose. Where it was cool to be bad."

A few weeks later, Michael left his mother's home and joined his father and stepmother in Charleston. He was enrolled into a private school, and hated it. "I wanted to be the guy who smoked weed. I was with all these damn white people that I'd never been around before because I was always in Black schools, and I just was like, man, screw this." He acted out on purpose, and was placed into a mental hospital for 10 days after an incident of self-harm. "I wasn't even out for three weeks, and I cut myself again," Michael told me. "And then they put me into a long-term mental hospital."

Michael stayed there for three months. As he put it, "it was a complete madhouse. Violence, gang stuff, sex, all kinds of things going on in there." When he got out, he lied about an abusive situation at home, and ended any relationship he still had with his father’s family. "I burnt this bridge, this nice life with a family that didn't even want to see me anymore," he told me. "But really, it was all just because I wanted to be with my mom and the life I had there."

Michael got what he wanted, and went back to living with his mother and embracing a lifestyle of smoking, drinking, and running "free." He failed out of high school, and worked sporadic construction jobs through his late teens.

When Michael was 19, his mother was diagnosed with HIV. Her doctors said that it was a slow progression and that, with the right medicine, she could feasibly live with it for the rest of her life. But her HIV medicine reacted with the high blood pressure medicine she was already taking. She had a massive heart attack and, a few days later, died. "I was 19, and I was already in a bad place in life," Michael told me, "and I ended up going really, really crazy."

Michael’s mother, Marian, holding Michael’s sister

The first time Michael wound up in jail, he went for three years. (He asked that the exact details not be shared publicly.) "When I got out, I thought that I was fixed," he said. "I'd gotten spiritual and all this stuff, and thought I was different now." He got a job working at a restaurant and lived in a halfway house in Savannah. But over the next few months, Michael discovered that his charismatic personality lent itself naturally to the shrewd business of drug dealing. "I sold drugs for a long time before I ever tried them," he said, "and I was this rich personality in this very dark society." If someone had a nice car or boat they wanted to sell, they knew to call Michael, who had plenty of connections and cash.

At first, he had no interest in using the drugs himself; he'd tried them all, and found the feeling terrible. But as he embedded further into the culture, he eventually did come to enjoy meth. He wound up back in jail for two more years on a possession charge, and when he got out, his life only became wilder. "I was out of prison for nine months, and it was the craziest nine months of my life," he told me.

Michael began looking for a normal job, but all around him were signs of decay and atrophy. "I literally paroled out to a trap house, man," he said, "and there was just all kinds of shit going on. It was way worse than it had ever been when I'd left. Everybody was just wiped out on drugs." He resumed dealing, and though he never joined a gang, he was being supplied by one, and became infamous for the scope of his network and distribution schemes.

Law enforcement began an investigation; Michael, along with 47 others, was arrested and indicted. When he arrived, he found out that the person who had brought him into the operation was telling everyone that Michael was the reason everyone else was now in jail, too. "This other guy had gone to jail for something unrelated about two months before, and was actually the confidential informant who got us all busted. But he starts telling everyone that I was the reason why everyone got locked up. This guy was real charismatic, and it made sense, because none of the actual evidence or paperwork had come out yet."

The gang Michael had been supplied by put a hit on him in prison because of all the accusations against him. "One day, these guys ran up on me and beat me real bad; broke my nose, deviated my septum, chipped one of my teeth." Michael survived, but when he received his sentence—20 years for trafficking—he was placed in solitary confinement. While there, a few officers stopped a suspicious janitor in Michael's hallway; on him, they found a note that simply said Michael’s name, and the acronym SOS: Smash On Site. "That's gang lingo for if you see him, you have to kill him," Michael explained to me. The officers in charge of Michael refused to let him out of solitary confinement after that.

During his nine years in prison, Michael was in solitary confinement for a total of two and a half years. He shared about his daily life. "Well, you can talk to your neighbors," he began, "but generally your neighbors are terrible people." Michael mostly kept to himself. When he first arrived in solitary confinement, he tried coming up with a routine. "I was like, Okay, I'm going to read a book for a while. Then, when I get tired of that, I'm going to do some push ups. When I get tired of that, I'm going to clean up the room. By then, it'll almost be dinner time, and I'll read some more. And pretty soon after I'll go to sleep." He told me about how he constantly tried to find something to do, to always have a task to keep his mind and body occupied. “Those months were the hardest adjustment,” he said.

Michael in prison

Eventually, though, he had something of an epiphany: what if he just did nothing? "One day, I just lay down on my bed, put my hands on my stomach, and I started thinking. And all of a sudden, it was, like, lunchtime. And I did it again after that. And next thing I knew, dinner was coming through my door. And I was like, 'Wow... I just chilled for a whole day.' I'd just learned to do nothing, and to be still, silent, thinking." He chuckled, and brought us back to the present for a moment. "I still do that. Sometimes, Shannon comes back into the house, and I'll just have, like, every light off and be sitting on the couch, thinking. I just learned to be still and not be bored." He'd inadvertently learned an informal version of meditation and reflection, and considers it to be among the few positive things he experienced while in solitary confinement.

Michael spoke of the power of time. "There aren't clocks in solitary. We didn't have air conditioners, but we did have an open window with bars behind it. And you'd look at the light and learn how to tell what time of day it was." He also read countless books, usually at least one per day, and talked about the social dynamics of having and borrowing something to read. "The book game in prison is funny, because when you go into a dorm, you always ask people 'Hey, you got a book I can get?' And they're gonna give you the most bottom of the barrel book you've ever seen in your life. I'm talking the cover's missing, Louis L'Amour, 1965 Western, and it's the second book of a series. And you read it, and maybe pages are randomly missing or the end might be gone because someone didn't like it and ripped it out."

The path towards better books, as well as higher social standing, Michael said, was basketball. "I always tell people, I survived prison by being good at basketball. And that's really not a joke, because that's how I got attention. Because people would be like, 'You're pretty good for a white boy! ' And after, I'd be watching TV, and talking to someone I played with, and they'd be like, 'Come over here.' And then I'd go with the person and they're getting something for me to read. And all of a sudden, now I'm looking at books all with covers on them. And eventually, you find out there's great books everywhere. But when you first get in prison, you're definitely not getting them."

Together, reading and sitting still provided ample kindling to reflect on his life. His thoughts were prompted, at least in part, by shame. "People were tired of writing me letters," he sighed. "And I realized that I wasn't a benefit to the people around me, at all, for years." He thought of his scant communications with anyone outside. "Every now and then, they'd roll out a phone on wheels, plugged into a long cord. And for months, I would call. And rarely would someone pick up. I wouldn't get mail for months. Nobody even cared that I was in solitary confinement."

"I realized, I've made some bad choices. I'm looking out the window in solitary confinement, and I was like, okay, if life's a game, then I'm losing right now. This is about as bad as it gets, right here." Michael began to choke up. "The whole time I was in solitary, I thought I was going to die. I thought I was going to be released from solitary confinement, and that I was going to be killed."

Michael after he got his tattoos in prison

He talked about what he missed from the outside world. "It's the simple things. You don't miss money, or jobs. You miss barbecues with your family; music playing on a speaker outside; all these people." Letters, he said, were a powerful way to document his emotions. "You write a lot of letters, and you end up having time to think about how much you miss these people. How bad you miss things. You just want to express that. And then you end up with these really incredibly powerful letters." He recalled how difficult the process was. "I would write all these letters trying to capture this moment," he said. "But in the end, I would fail every time. There was just no way that I could get this message of suffering through on this paper. But what happens in the process is you write really good things, even if they may just be attempts at describing what you're actually experiencing."

He reflected on how he got to that point in life. "You hear a lot of stories of people who had great upbringings who ended up on drugs..." he paused for a moment. "I hope this is okay to say... but I really think that with me, the whole thing was avoidable. I don't actually know if I was ever really a full-out addict." He shared again how he'd seen a better life; how he'd enrolled, however briefly, in a nice private school, and how he'd been so curious as a child. I wondered aloud whether he thought that seeing that life, knowing it existed, somehow gave him a subliminal worldview different from those who only knew poverty and a darker life. He said he wasn't sure.

He spoke of one book series in particular called The Wheel of Time, a fifteen novel epic fantasy series, and how it prompted a bit of a realization. “I had an epiphany about what I said before; how I thought it was cool to be bad. I was like, oh my goodness, I've had it all wrong. I started to see the value in humility. And it got me realizing that I had to fully accept, as I do now, that I'm average. There's tons of people better than me at every single thing I can do. And I'm okay with that. I just want to be peaceful, and to leave the world better because I was here. And I've got a lot of work to do on that front."

In addition to fantasy novels, Michael also read legal texts, and often represented himself in court proceedings. "I ended up kind of being a so-called chain-gang lawyer, filing my own motions, and even a lawsuit one time." With his knowledge, he was able to reduce his sentence from 20 years to four, and was released in 2018.

When he got out this most recent time, none of his family was sure whether he'd really be any different from the other times. His sister, Laura, told me, "I was so hesitant about having a relationship with him after all he had been through. I just, like, didn't know who he was anymore. But the second I saw him, I knew he had totally changed, for good. That cloud of anger and tension was just gone, and you've probably seen it now, but he just radiates positivity and joy. He's completely opposite from what he was before, and it's so beautiful."

A social media post Michael made soon after he was released from prison

When Michael got out of prison in 2018, he had no interest in getting into a relationship. "I really didn't have the need for companionship," he told me. "I'd become deeply comfortable with just being by myself, being alone, and I was just thinking, I gotta get my life together. I don't have time for a relationship right now. I've wasted too many years already." His father owned an old pressure washer, and with that Michael began to work and build his own business, staying busy through his work and establishing the financial foundations for a life that would help keep him out of prison, for good.

His ideas of romance only changed after he got into a scooter accident; a car side swiped him on the road in a hit and run, and Michael went into a coma for a day. For two weeks after the wreck, he woke up each morning having totally forgotten what happened the day before. "Finally, one day, I walked up to my stepmom and was like, 'Where's my scooter?' And she handed me a piece of paper with answers on it to questions that I'd kept asking, but couldn't remember."

Part of the paper Michael had to remember what had happened to him after his scooter accident

"When I was recovering, I started having second thoughts about wanting to stay single," he told me. "I was running my own pressure washing business and working at a restaurant, 60, 70 hour weeks and stuff. And after the wreck, I was like, wait a minute... if I can find something really, really good... why not?"

Neither Michael nor Shannon have strong impressions of the first time they met in October 2018, Shannon because Michael was so quiet, and Michael because he literally doesn't remember. "My memory fluctuated a lot for a while after the accident, and so one afternoon, I met Shannon, when Laura took us to a place to have a beer together. And... I don't remember." He and Shannon laughed, and Shannon recalled her side of the meeting. "All I really remember about him was that he was kind of quiet and, you know, pretty cute. But I didn't really think anything of it."

Michael and Shannon hanging out with his sister, Laura

They met a second time at a bonfire that one of Shannon's high school friends hosted, a yearly tradition her friend group had each December. Michael came with Laura, and when Shannon saw him, she went over to say hi. "I was like, 'Yo, what's up! Nice to see you again! ' And I could tell he didn't remember me, so I reintroduced myself, trying to be chill or whatever.” They talked for a bit, but naturally drifted into other conversations.

They met a third time at a New Year's party a few weeks later, and this time, something was different. "We just hit it off for some reason that day," Shannon recalled. Both tried to keep things casual, making an effort to also talk to other people. But each time they did, they found themselves back in conversation with one another. “We kept ending up locked in dialogue,” Michael said, “and even in my inebriated state, I recognized that something special was happening.” Shannon added, turning to Michael, “I remember that you were so respectful, and weren’t flirty or forward at all until later.”

Towards the end of the night, Shannon didn't want to drive home, and Michael offered that Shannon could stay in his room if she felt comfortable. Shannon laughed, recalling what Michael said. "He was specifically like, ‘Don't worry, I'm not gonna try anything! ’ But if I wanted to sleep somewhere more comfortable, that I could go there."

After Michael went upstairs to his room, Shannon pondered his offer; she decided to take it, but as she walked up the stairs to go to his room, Michael's stepmother, whose bedroom was right next to the stairs, stopped to talk to her. She enthusiastically offered that Shannon could stay in her room. Refusing and admitting her original intentions felt too awkward, so Shannon obliged. Michael chuckled, remembering how awkward and sad he'd felt when Shannon never showed up.

After that New Year's, Shannon and Michael began to talk every day. They told me about a certain power in their interactions. "There were these moments that were so powerful and unique to all of our experiences, and values, and ideas, and identities, all coming together to this one unique moment that could only be experienced by the two of us," Shannon told me. She shared a particular example. "Early in our relationship, we were at this one club we go to all the time called The Commodore. And as we're leaving, there are a few homeless people outside, and since we're both the type of people who will just talk to anyone, we start having this conversation with this guy. And he's talking about how he needs a ride, and Michael immediately was like, 'Yeah, I'll give you a ride! I'll even go pick up some food for you, too.'"

Michael and Shannon with one another soon after they started dating

She continued. "And so the guy gets in the car, and we’re having this whole conversation with him, picking up some food and some groceries and dropping him off, like 45 minutes away. And keep in mind, Michael and I are kind of early in dating. And he hadn't said anything to me, like, 'Are you okay with this?' He was just like 'Yeah, yeah, come on in! ' And with someone else, maybe Michael doing that would've been a bad sign, but for me... afterwards, I was kinda just thinking to myself, 'Whoa... I think… I might be falling in love with Michael.' Because he acted like everything I would want in how I conduct and live my life. And I never felt that comfortable with anyone else in my life."

Each quickly became a part of the others' family. Shannon, who had long been friends with Michael's sister, Laura, was already close with his family, and Shannon’ family quickly absorbed Michael into theirs. Sydney, Shannon's sister, told me, "I'm trying to think of the first time I met Michael, and I genuinely have no idea, because he really just has become family."

Shannon and Michael with her family

A year and a half after they met, around May of 2019, Michael began to think of how he'd like to propose. Knowing Shannon didn’t want a diamond ring for ethical reasons, Michael instead had one made with an opal stone as the starring gem.

Shannon and Michael’s wedding rings

Michael asked Shannon's parents for their blessing (they happily gave it) and planned his proposal. A few minutes away from his and Shannon's home is a new public parking garage that, for some unknown reason, is rarely actually filled with parked cars. The top, eight stories up, opens up to the Charleston sky. Michael and Shannon often drove there to sit on their car and watch the sunset.

Before the proposal, on June 19th, 2020, Laura invited Shannon to get her nails done together, and Michael told Shannon to dress up nicely that day so they could “go to a nice dinner together.” Come evening, Michael instead drove her to the top of the parking garage, where both her and Michael's families were waiting. They'd rolled out a rug that resembled an aisle; Michael stood at the end of it, and as Shannon walked down to meet him, she saw that they'd also assembled a small table with a few candles and pictures of Michael's biological mother.

Michael and Shannon after their engagement

A proposal, and marriage, is an inherently optimistic choice, a vote of confidence that the future is better spent together with someone than apart. For Shannon and Michael, that future is full of ambition. "I wouldn't be surprised if, down the line, the two of them are working together on a national program," Shann, Shannon’s father, told me one day, "where they're helping the homeless, or hungry, or any others in need."

Michael, in particular, is keen not to forget about his years in prison, and to use his experience there to inform his role in advocacy. He told me about how his experiences colored his notions of institutionalization in the US, and how harmful that system was. “This story is ultimately about me and Shannon’s love story,” he said, “but if there’s anything else I hope others take away from it, it’s the propensity of American society to push people towards institutionalism when they don't fit into a specific box, and how harmful that is. If you learn different, you’re put on medicine. If you act different, you’re put into an institution. And rarely once you enter do you leave after one experience.”

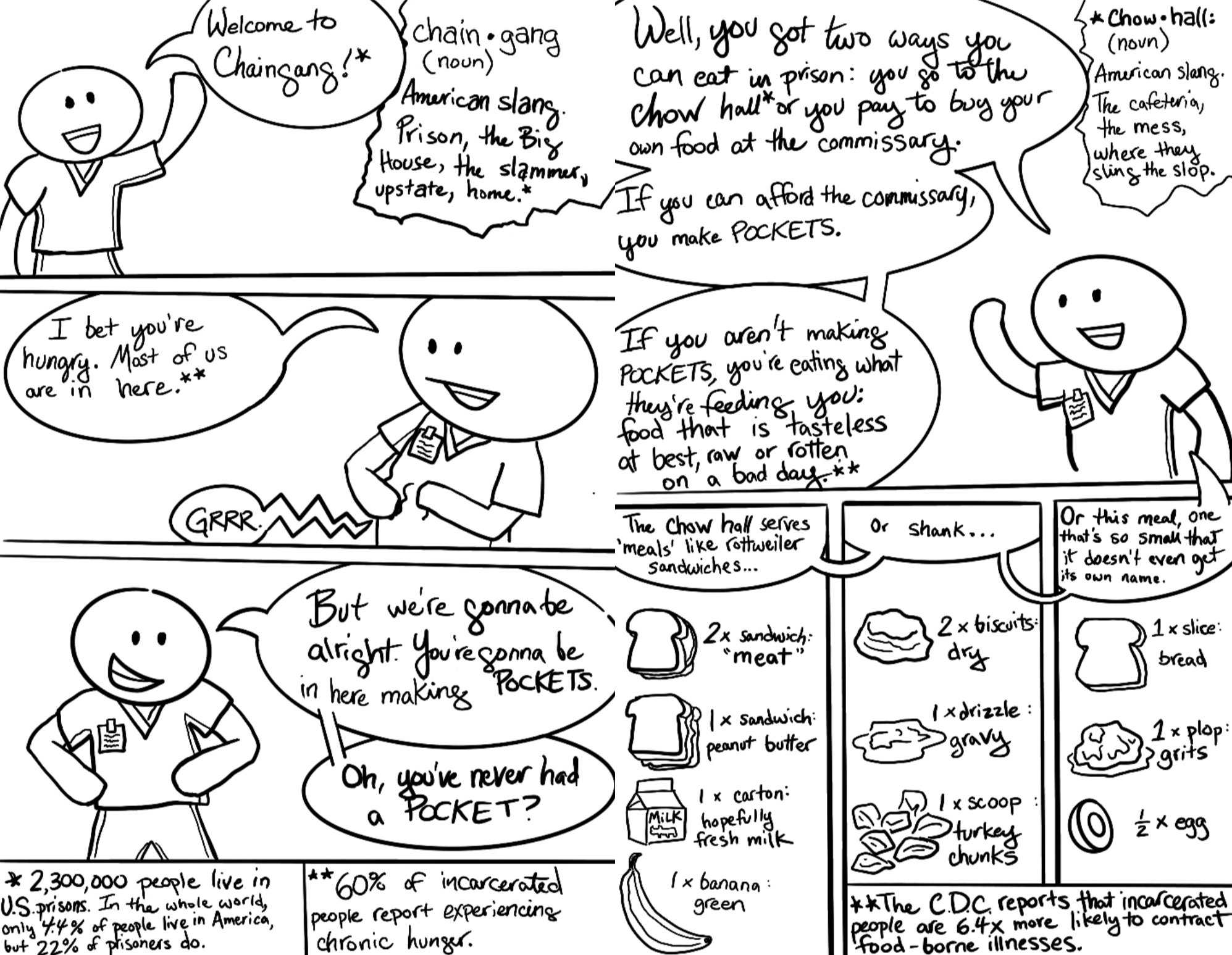

Most of the people he met in prison, he said, had been there before, and before that had been to hospitals or mental institutions. “It’s a terribly circular system, and it’s a rarity for someone like me to break out of that cycle.” He gave a concrete example in the form of stories about a part of prison that I’d never heard about before: the art. "All those years I was in prison, there were these old men,” Michael said, “and their life in there was to wake up every day and create a piece of art. Whether it's drawing on an envelope, or carving something, or making a necklace, these people do this every day, because they're hungry. There's literally not enough food coming out, and so everyone wants to buy and eat more from the shop. But many of these people who have life sentences don't have anyone sending them money."

The first two pages of a zine Michael made about supplemental nutrition in prisons. You can read the full zine here.

"So, they create art. And after 30 years, they get really, really, really good at it." He talked about their process, and even showed me a piece that someone had made and which he'd kept. "This is a bedsheet that was cut with a razor blade," he began, "and then they layered floor wax on it, the kind they use to shine tile floors. And they kept coating it on until it made the sheet firmer, like canvas. Then, to make paint, they broke open colored pencils, melted it, and mixed it with baby powder so it wouldn’t dry back up. For the brushes, they used toothbrushes filed down to different lengths. And then they painted this.”

A piece of art made by someone in prison using a bedsheet, melted colored pencils, and different length toothbrushes

He returned to his personal experiences. "I would see these artists in prison, and I'd ask, 'What are you doing, man? '" He explained it was a way to get to deeper questions without asking them outright. "It's socially unacceptable to ask people, 'How long do you got left? What are you in for? ' You just don't ask those kinds of questions immediately. But people do want to tell you. You start to talk to somebody for a while, and eventually you feel like you can ask those questions. And I can't tell you how many times I'd talk to these artists and end up asking, 'How much time do you got?' And they'd be like, 'Man… I got life."

We had this conversation one afternoon while at a local restaurant for lunch. Michael shook his head, becoming visibly emotional. "Even right now as we eat, they're probably at a prison table drawing on a fucking envelope. And they're never gonna stop; that's it for them. Their art is never going to be famous or worth more than ramen noodles. And it should be."

He spoke of a nonprofit he'd recently founded, Be No Good, to showcase this side of prisoners' lives. "I'd like to organize a traveling art exhibit of inmates' art, tell the stories about each inmate that created it, and use that platform where everybody is blown away by this art to tell them about the needs for reforming the justice system."

Homepage of Be No Good’s website

As Michael talked, Shannon looked onwards, smiling. I could tell that, even though she'd heard this story many times before, she was still proud and impressed and grateful for Michael. She talked of wanting to support him in his dreams alongside pursuing her own. “I really want to get a PhD,” she told me, “and I’m interested in going into academia or the nonprofit education sector.” Her focus, she told me, would be on two things: liberating minds through the lens of social justice and activism, as she needed when she went to Ashley Hall, and prejudice reduction. “Basically, making us less racist,” she described, sharing dreams of creating a fellowship for young people to create their own “prejudice reduction interventions,” while adding a layer of academic research on various methods and their efficacies.

Even before they met, both Shannon and Michael also had dreams of eventually buying and building on their own land. "We want to eventually do a homestead," Shannon said. "Buy some land, build a home, have a garden, chickens running around, and just building stuff." Shannon's father also told me about his excitement for the potential of Michael becoming a father. "Michael's a little older than Shannon," he said, "so it's possible he could just leave that part of life alone. But I don't think God's gonna let him get away with that. Because he has this innate, God-given father, parenting quality in him."

Shannon and Michael during their wedding ceremony

Shannon and Michael's wedding, held in mid-March 2021, mirrored many elements of their proposal. Because of COVID, they gathered just a small group of 20 people. Next to their wedding arch was a small table with a candle and picture of Michael's biological mother; towards the beginning of their ceremony, Shannon's father, who served as their officiant, announced, "Michael and Shannon want to take a moment and honor his mother. They're going to light a memorial at this time." The two walked a few yards from the arch to the memorial, and lit the candle together. They stood quietly in front of the picture for another minute or so.

Michael and Shannon honoring the memory of his mother

Neither Michael nor Shannon would consider themselves to be very religious anymore, but both still honor and respect its power and meaning. Shann's message was largely spiritual. "The world has the idea that marriage is simply a legal contract. And it is a legal contract. We don't take it lightly. But at the same time, marriage is a spiritual covenant. And if you study the word covenant, it's a whole lot stronger than contract. And so with that in mind, we are watching Shannon and Michael's faith. The power of their faith will unite them together; and the two shall become one."

Shannon’s father officiating the wedding

Michael and Shannon both have a certain kinetic energy to their lives; those around them can sense that they're constantly in physical and emotional motion. They speak to strangers, laugh with each other, cook, fight, build, together. And as much as they've already achieved, they have so much more they want to do.

I first began this project with the thesis that weddings represent something uniquely universal across humanity; that they were a kind of celebration held in countless ways among countless cultures, but always with the same core emotions of optimism, hope, and joy. But I also thought of another event with a similar universality and emotional weight: a funeral. Unlike weddings, funerals often mourn the past, rather than celebrate the future. But like weddings, funerals have the ability to bring together the closest people in someone's life: friends, family, entire communities.

When Michael was in prison, he didn't think about his wedding. But he did think about his funeral. And he knew he wanted it to mean something. "When I thought I was going to die in prison, I had this thought," he said. “No matter how long I live, whether to 19, or 90, it's really not going to matter much in the grand scheme of millions or billions of years. And so I decided that I was going to create happy memories. That I was going to make a positive impact on the world. That I was going to use where I'm at right now to bring hope to people and try to fix some things. Because my greatest fear was that I was gonna die... and have wasted my life."

"I thought, What will my funeral look like right now? What would people say? He robbed me. He hurt me. He was never a happy kid. It would be the saddest funeral ever. Hardly anybody was gonna show up. And I told myself: If I get another chance at life... if I don't die here in prison... I'm going to make sure that my funeral is going to be beautiful. That people are going to have good things to say about me."

Michael had begun to cry; Shannon wrapped her arm around him. "And I'm proud to say, right now, people would. I did end up getting another chance at life. I've been the best person I can be… even when no one's looking…” He sniffed, and smiled at Shannon. “And it's working."